Cherokee Jack by Richard Phibbs for Man of Metropolis | Minnesota History of Mankato Hangings

/Anne of Carversville rarely gets behind new models, except for the refugee models out of Africa. We are their biggest champion in a collective sense.

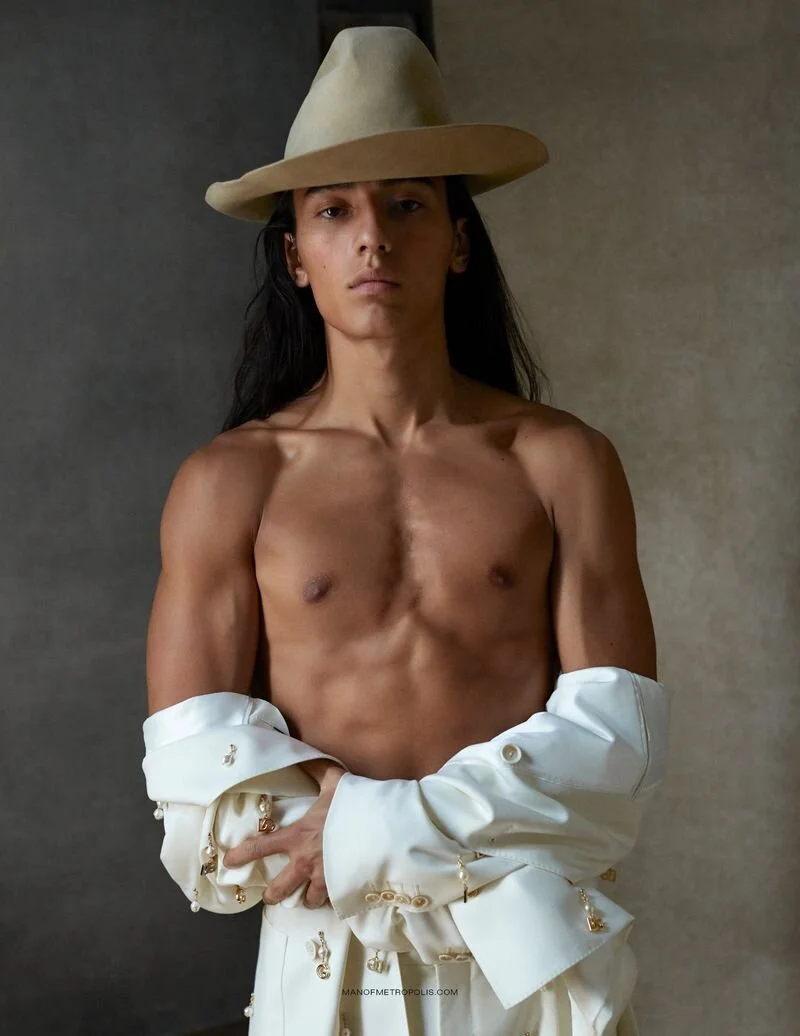

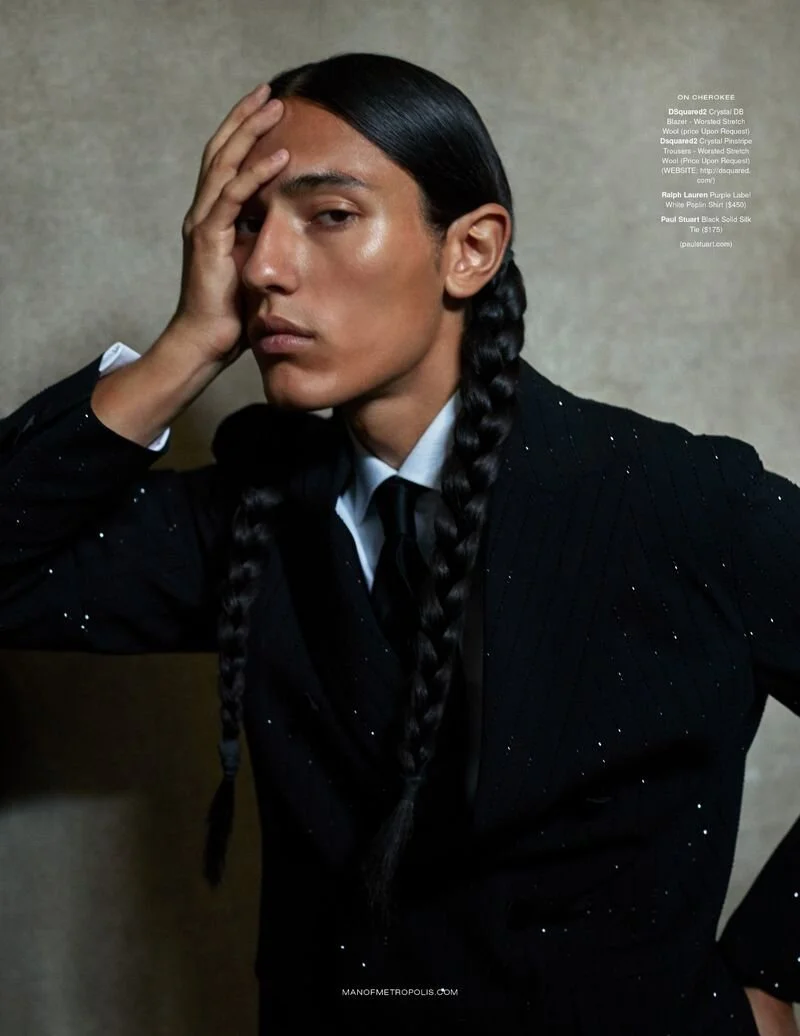

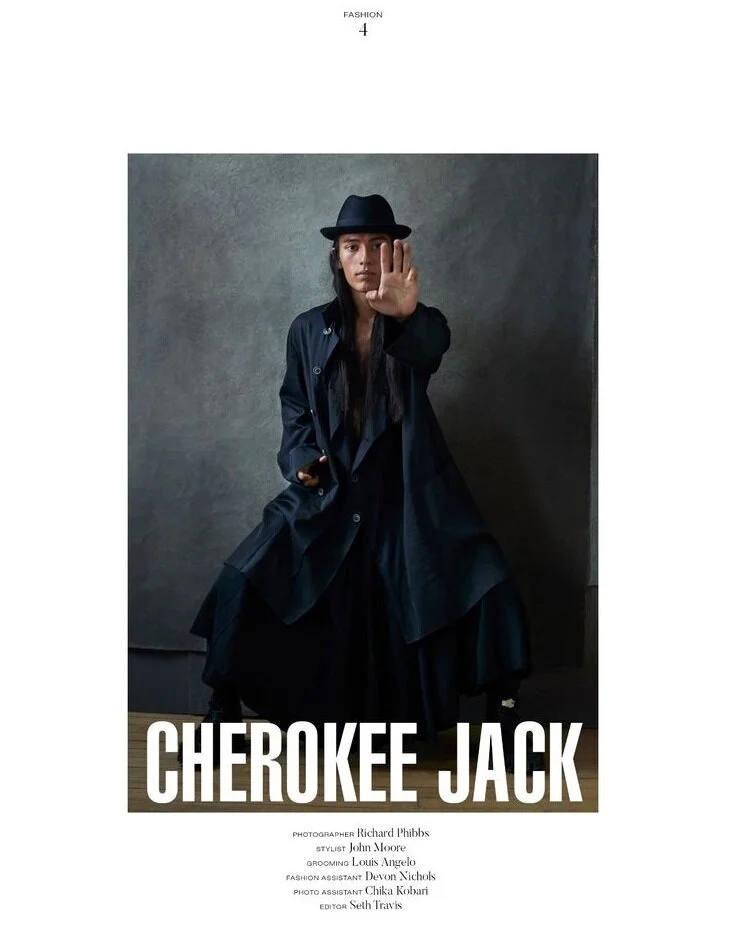

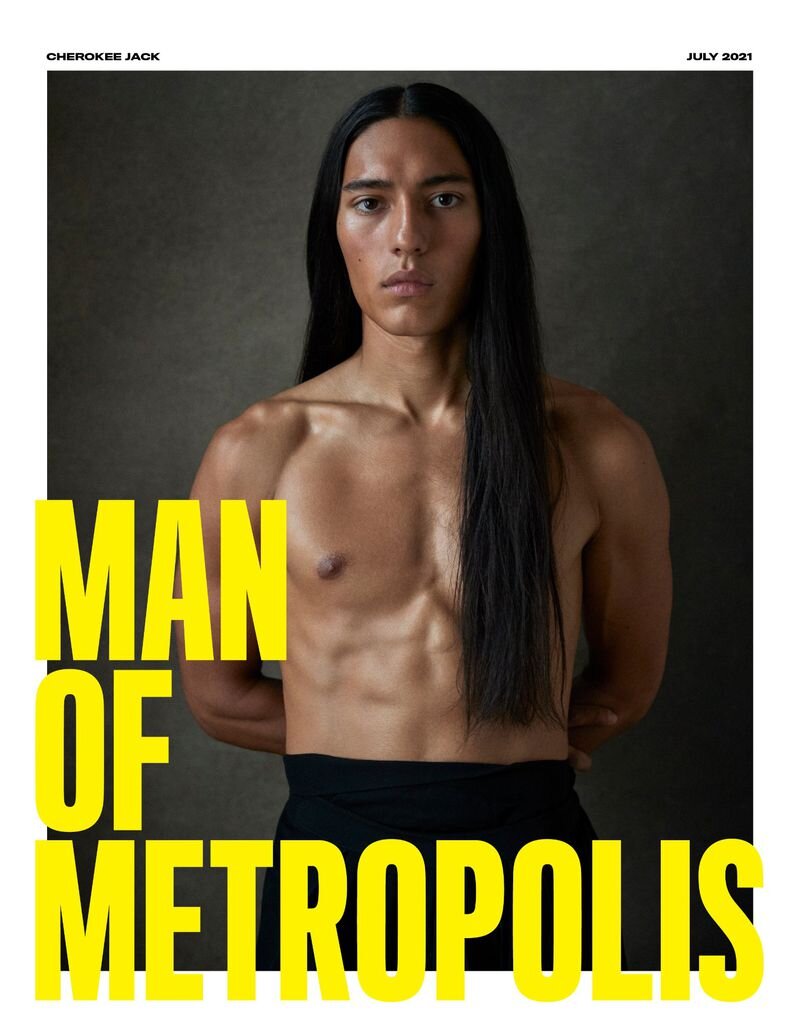

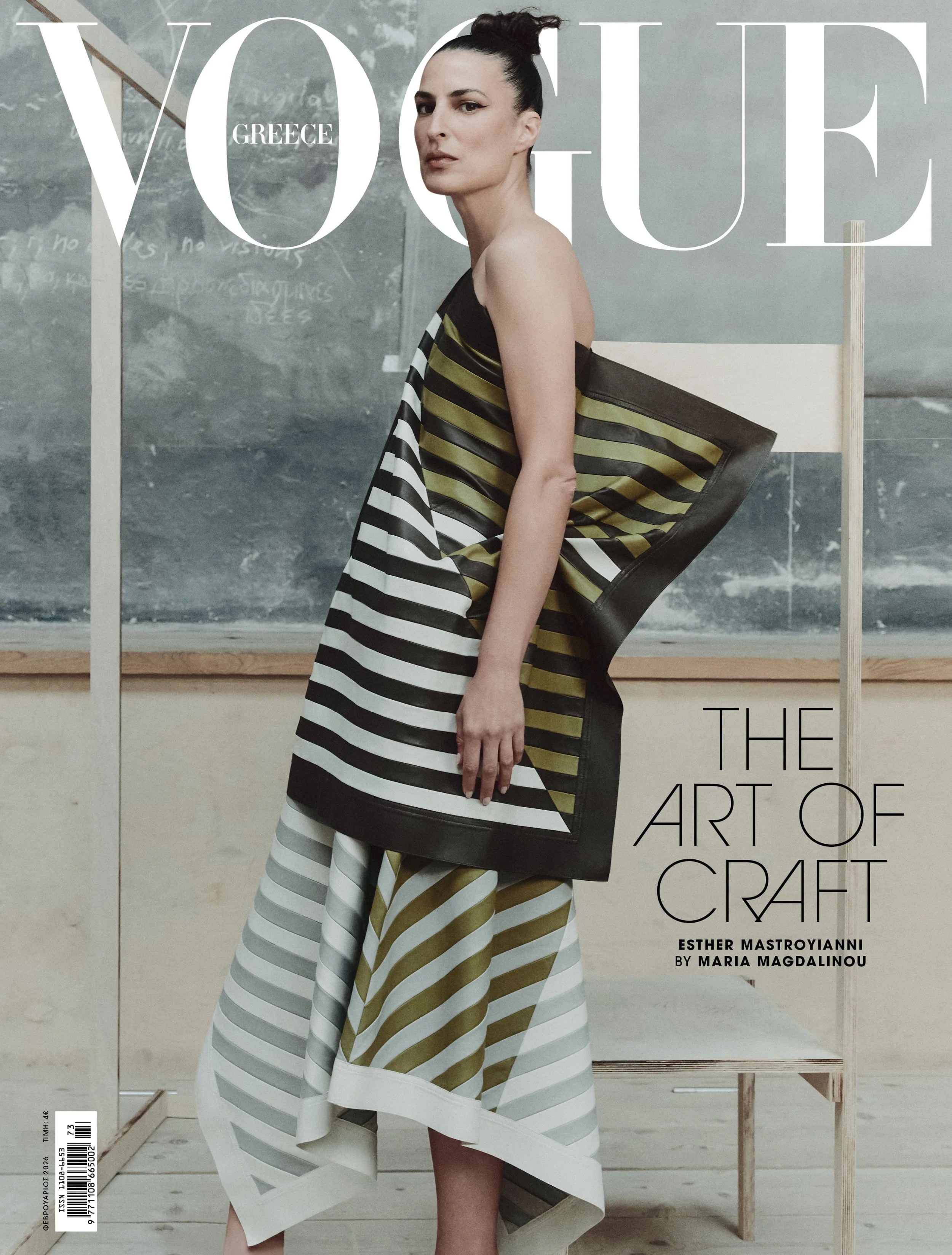

However, within the context of this moment — how my brain is operating on July 15, 2021 — it’s impossible for me not to comment on the visceral response I’m having to the ‘take my breath away images’ of Cherokee Jack by Richard Phibbs.

When high-integrity images are so beautiful that they move me to tears, I must respond to the gift.

When through its exquisite beauty, a fashion story quietly addresses the brutal facts of American history and the suffering meted out to native peoples in America, my words cannot possibly do that fashion story justice.

When images prompt me to apologize on behalf of OUR [Cherokee Jack’s and mine in 2021] country to his ancestors, the pictures have impact way beyond their initial exposure in a high-quality, men’s lifestyle magazine.

The editorial serves as a reminder of how a model and a stylist and a photographer can work together in perfect synchronicity — with an editor who shares the same vision. It also helps that the photographer has the technical and artistic vision of Richard Phibbs.

Images like these of Cherokee Jack by Richard Phibbs trigger different memories for all of us. Many have nothing to do with Cherokee Jack, or his lineage. I don’t connect Cherokees with Minnesota in any way, to be honest. But I am know-nothing on the topic.

My track record on racial justice is a high-integrity one. It’s in my DNA, and while I’m certain that I’ve faltered in small ways, I’ve been present for the fight for racial justice in America, almost since the day I could breath.

My concern is the story of America’s native peoples. I will never remember what I wrote in a play that was presented by my eighth-grade American history class in Mankato, Minnesota. We were supposed to write some essay, answer a question — I don’t remember.

Yours truly wrote a play about Minnesota and statehood for our history class. Next thing I knew, the teachers had reviewed my play and decided that it was worthy of being presented to the entire school.

Overnight, Peony Girl [my young girl self] became a eighth-grade playwright, basking in my new role as director. We even had historical costumes, as the teachers went all out for my little production.

All I can say is “I am so profoundly sorry” about the Mankato Hangings

What bothers me is that I don’t remember what I said in the play about America’s indigenous peoples — we called them Indians then — people whose ancestors surrounded us everywhere in Minnesota.

My home state of Minnesota was admitted to the union in 1858, four years before 38 Dakota men were hanged on December 26, 1862 in Mankato. I moved to Mankato from a tiny town called Lake Benton, not far from a Sioux reservation in South Dakota.

I remember General Sibley, who had a major role in my play. But my mind is blank on his decision regarding the hangings. I learned this story a couple years ago, as it wasn’t taught in the Mankato schools back then. Researching lynching in the US for the last five years, I came upon the Mankato hangings history in my research as part of The US-Dakota War of 1862.

4000 people crammed the streets of Mankato to watch the lynching of 38 Dakota men. It was common for large numbers of white people to turn out for a public lynching all over America.

Today’s Republicans would condemn it as unfair and biased, anti-white, critical race theory, but I wonder if anyone has written a book on the “public spectacle of lynching”. They were not moments of anguish and horror for the spectators. Rather, white people cheered at hanging the ‘savages’, as if they were at the Roman Colosseum.

These images of Cherokee Jack prompted me to tell the story of my little sixth-grade play about the founding of my home state of Minnesota. That proud event in my life is forever tied to this moment decades later when I admit publicly — and not only on Facebook which I did a couple years ago — but here on AOC, that I am somewhat tormented over the possibility of romancing the history of what was going on in what would become the state of Minnesota.

I was always ‘adopting’ the unfortunate, even in second grade. But I can’t tell you that the lives of 11 indigenous tribes in Minnesota had any significant part in my proud-girl play. That fact really bothers me.

Make no mistake, I was assertive and fearless enough to have told the story of the Mankato hangings. I would not have buried the history if I knew about it, even at that young age. For certain I would have included the hangings in the narrative and refused to participate if my teachers wanted the scene cut from my play.

My concern is whether or not the history of the Mankato hangings was taught in my Mankato school. I believe it was not, or I wouldn’t have been so horrified over discovering the story decades later. Now I am taking the opportunity to share one moment in Minnesota’s history, four years after it joined the union as a free state.

I close with this nod to the nobility of the Dakota men who were lynched the day after Christmas in Mankato, Minn., taken from The US-Dakota War of 1962. I know the exact location.

On December 26, 1862, 38 Dakota men were hanged at Mankato.

At 10:00 am on December 26, 38 Dakota prisoners were led to a scaffold specially constructed for their execution. One had been given a reprieve at the last minute. An estimated 4,000 spectators crammed the streets of Mankato and surrounding land. Col. Stephen Miller, charged with keeping the peace in the days leading up to the hangings, had declared martial law and had banned the sale and consumption of alcohol within a ten-mile radius of the town.

As the men took their assigned places on the scaffold, they sang a Dakota song as white muslin coverings were pulled over their faces. Drumbeats signalled the start of the execution. The men grasped each others’ hands. With a single blow from an ax, the rope that held the platform was cut. Capt. William Duley, who had lost several members of his family in the attack on the Lake Shetek settlement, cut the rope.

After dangling from the scaffold for a half hour, the men’s bodies were cut down and hauled to a shallow mass grave on a sandbar between Mankato’s main street and the Minnesota River. Before morning, most of the bodies had been dug up and taken by physicians for use as medical cadavers.

I apologize to Cherokee Jack and Richard Phibbs and Seth Travis of Man of Metropolis magazine, for taking such lavish liberties with this fashion story. Then again, we live in extreme times, don’t we.

I think the universe will bestow good energy on my action, as will Richard Phibbs when he finds out about it. Hopefully Cherokee Jack will benefit from this shout-out as well. This isn’t the first time Phibbs has prompted my personal narration skills with his photography. But today he has me by the throat, and he didn’t bring any tissues for my tears. ~ Anne