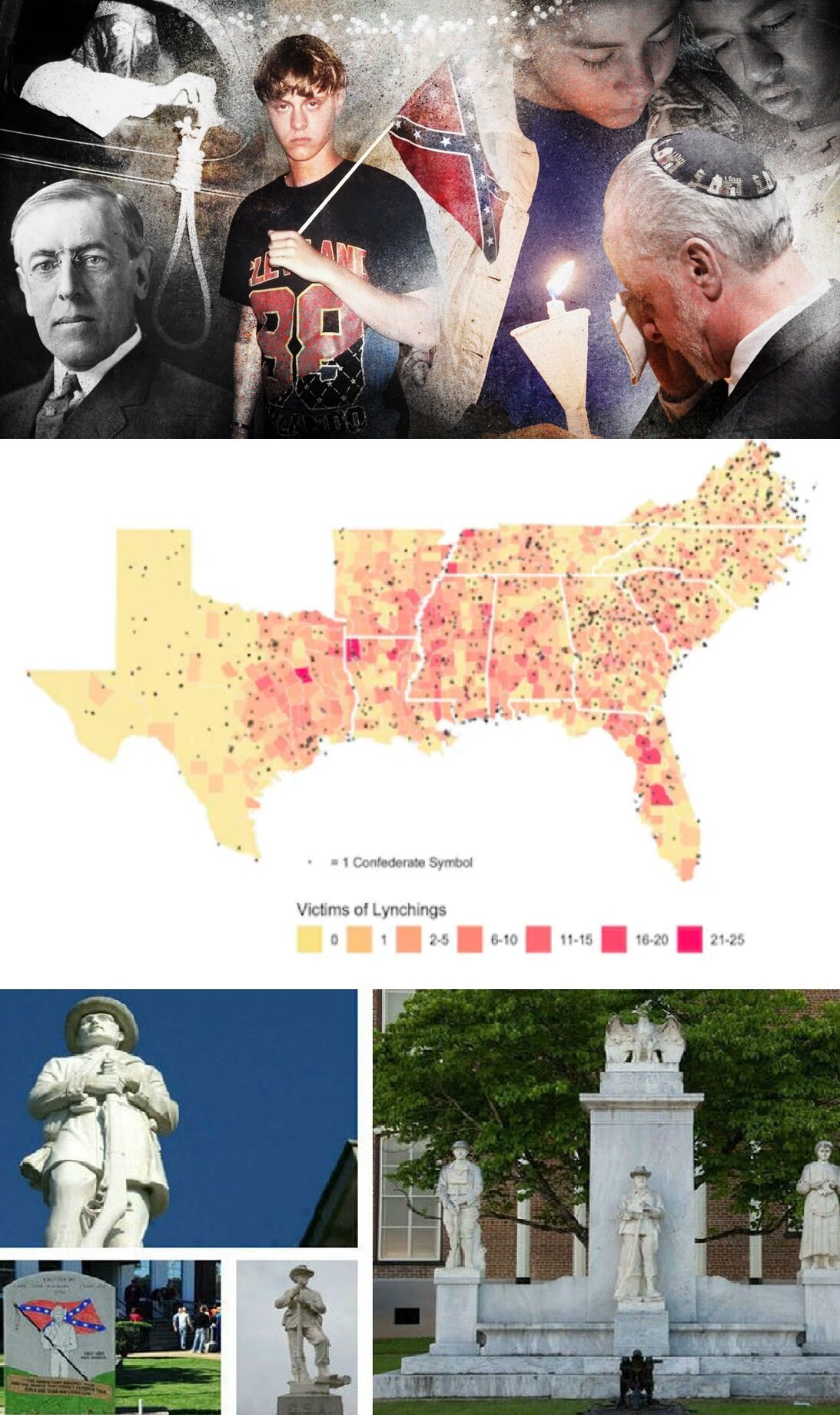

Charlottesville, VA Will Donate Robert E Lee Statue for Meltdown into New Art

/The Jefferson School African American Heritage Center is a cultural arts and history center whose mission is to honor and preserve the rich heritage and legacy of the African-American community of Charlottesville-Albemarle, Virginia. Additionally, the heritage center promotes a greater appreciation for and understanding of the contributions of African Americans and peoples of the Diaspora locally in Charlottesville, across America and globally as well.

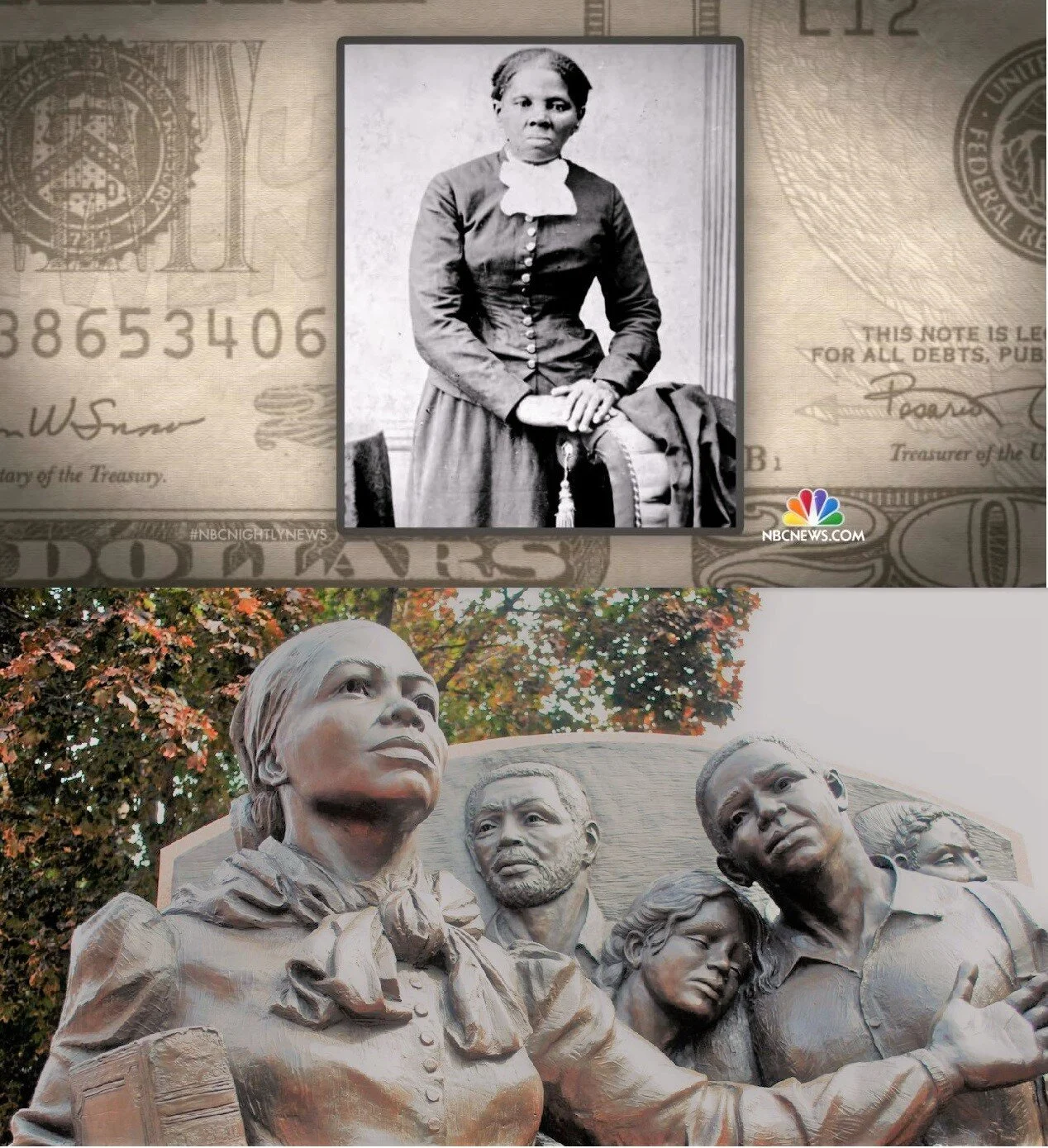

In a modern-day Confederate statue cremation, the controversial statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee will be donated to the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center. Plans are for the statue, which lived at the center of the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, to be melted down into materials for a new piece of public art.

Support Indie-GoGo Fundraising Campaign

An Indiegogo campaign page for the project said that its leaders wanted to “transform a national symbol of white supremacy into a new work of art that will reflect racial justice and inclusion.”

Related: Charlottesville’s Statue of Robert E. Lee Will Be Melted Down New York Times

Charlottesville’s Robert E. Lee statue will be melted down by city’s African American history museum Washington Post

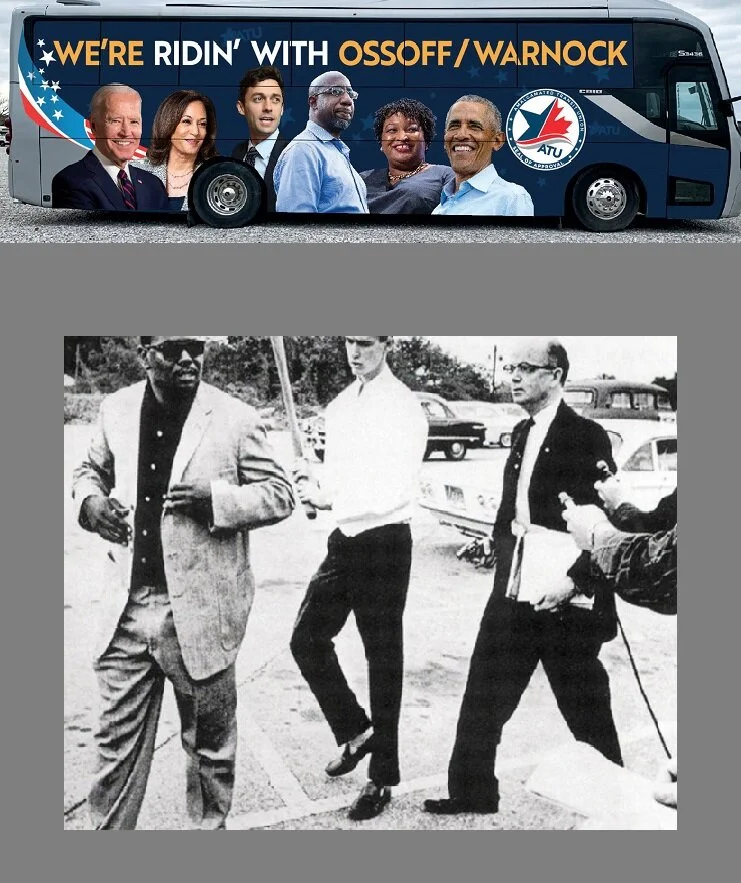

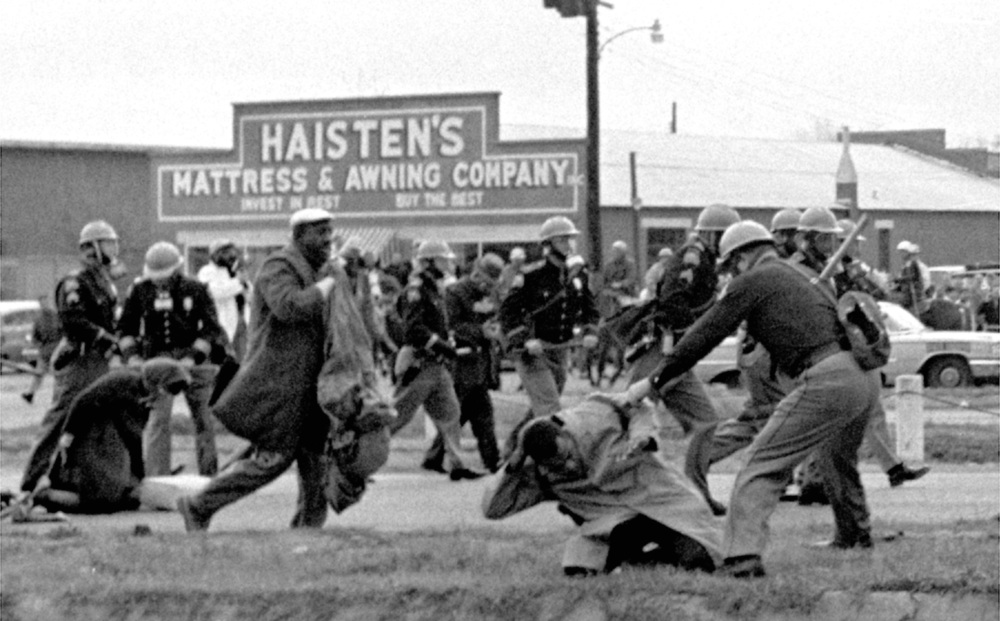

Correlation Exists Between Lynching Events and Confederate Statues by US County

/A map [middle image’ highlights the correlation between lynchings and Confederate monuments in America. The darker, redder colors indicate higher numbers of lynching victims; with each dot representing a Confederate monument (courtesy of the University of Virginia)

Republish via AOC at FeedBurner CC 3.0 License Attribution Required: Daily Fashion Design Culture News

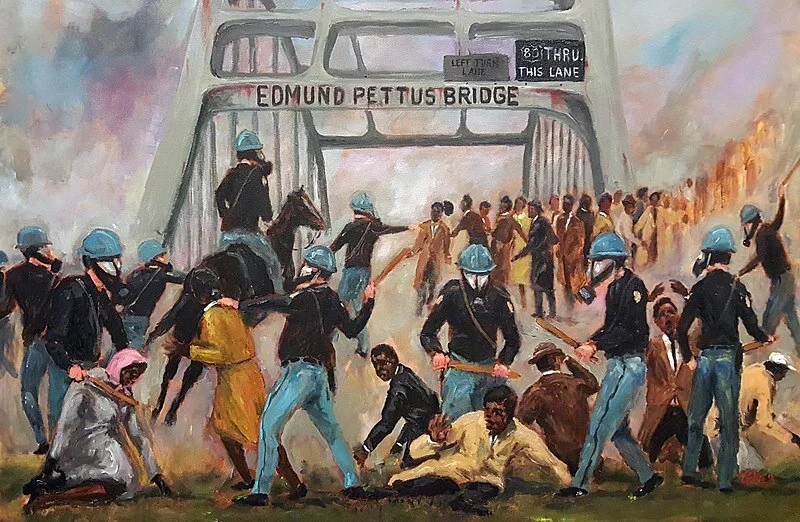

Large numbers of white southerners have long argued that Confederate monuments exist exclusively as symbols of southern pride and a proud history of rebellion against America’s federal government.

Led by United Daughters of the Confederacy, supporters of Confederate monuments refuse to acknowledge that there is any psychological damage to nonwhite people living their daily lives in the shadows of these relics to the days of slavery.

Former slave families should also celebrate the honor of the Old South, say white southerners while waving their Confederate flags in their faces. If people of color are bothered by these towering monuments of famed Confederate generals, they should praise God’s creation of an ideal society and way of life. Otherwise, people of color can hop the first boat back to Africa. Easy peasy.

A new study by researchers at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville challenges the noble premise of Confederate monuments.

Led by Kyshia Henderson of UVA’s Social Psychology Program, who worked with data scientist Samuel Powers and professors Sophie Trawalter, Michele Claibourn, and Jazmin Brown-Iannuzzi at the university’s Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy, the researchers documented a significant correlation between the numbers of Confederate monuments in an area and the number of documented lynchings from 1832 to 1950.

Published by the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers do not assert that the existence of Confederate monuments causes or provokes lynching. Their private beliefs — and those of the majority of researchers working in this area of study — do believe that Confederate statues are symbols of hate and also dominant power. But this study only concludes that there is a positive correlation between the two data sets: lynchings by county and Confederate statues by country.

“We can’t pinpoint exactly the cause and effect. But the association is clearly there,” Trawalter wrote. “At a minimum, the data suggests that localities with attitudes and intentions that led to lynchings also had attitudes and intentions associated with the construction of Confederate memorials.”

The researchers referenced another study associated with dedication speeches for Confederate memorials, finding that nearly half of the 30 dedication speeches reviewed involved “explicit racist language,” including phrases like “love of race” and “your own race and blood.”