The Horrors of the 'Great Slave Auction': Mar. 2 1859 at Butler Island and Hampton Plantations

/By Kat Eschner. First published on Smithsonianmag.com

On the eve of the Civil War, 158 years ago, the largest sale of enslaved people in the U.S. ever to occur took place.

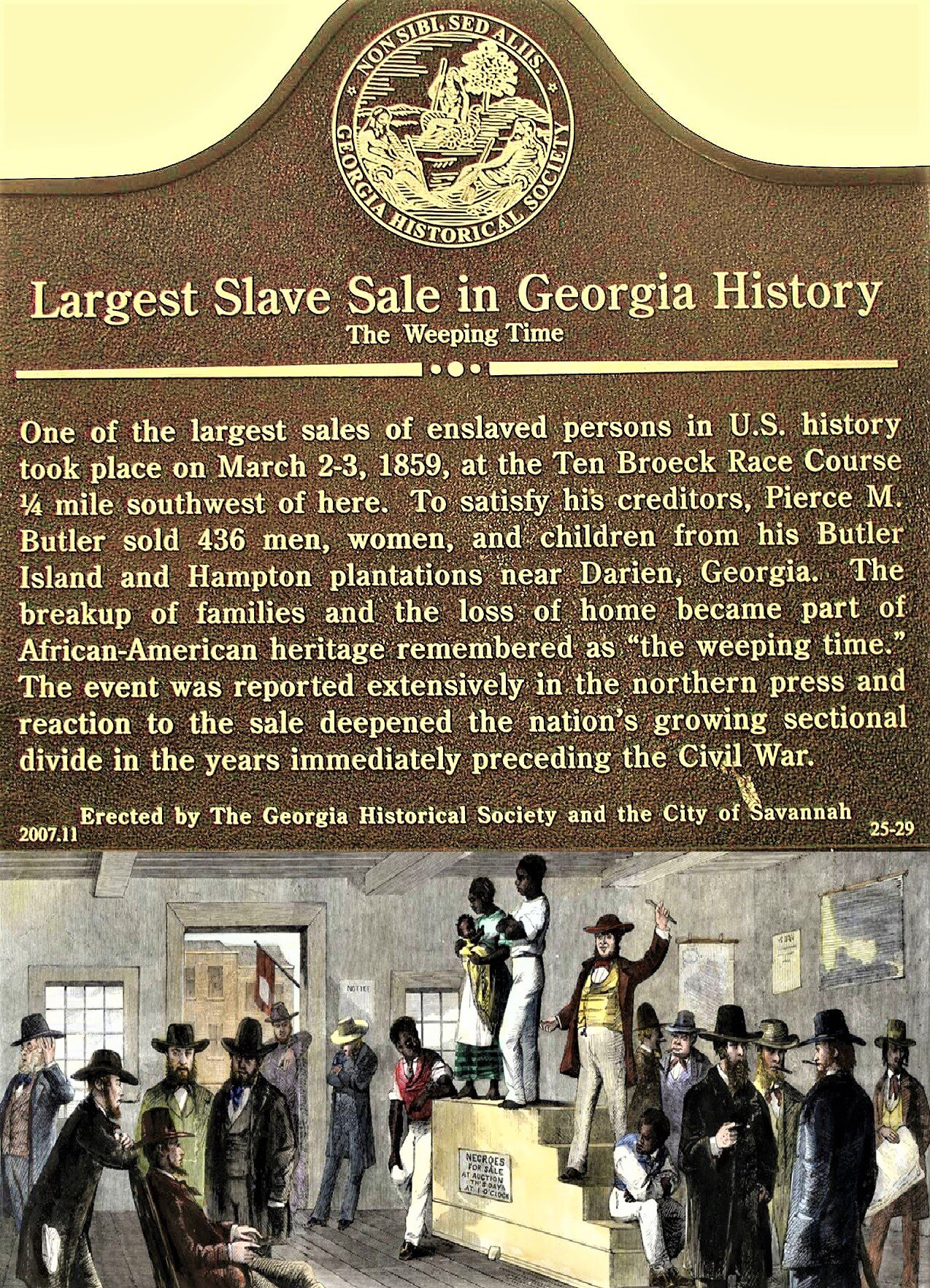

A plaque erected by the Georgia Historical Society on the Savannah, Georgia, racetrack where the sale took place—and which is still used to this day—offers a brief synopsis of what happened, excerpted here:

"To satisfy his creditors, Pierce M. Butler sold 436 men, women and children from his Butler Island and Hampton plantations near Darien, Georgia. The breakup of families and the loss of home became part of African-American heritage remembered as 'the weeping time.'"

The story has a lot of layers, writes Kristopher Monroe for The Atlantic, and it’s telling that only a single, recent plaque remembers the Weeping Time while Savannah is home to a “towering monument to the Confederate dead” erected a century ago.

The man who owned the slaves that were sold at the “Great Slave Auction,” called such particularly by Northern reporters who covered the sale, inherited his money from his grandfather. Major Pierce Butler was one of the country’s largest slaveholders in his time, Monroe writes, and was instrumental to seeing that the institutions of slavery were preserved. “One of the signatories of the U.S. Constitution, Major Butler was the author of the Fugitive Slave Clause and was instrumental in getting it included under Article Four of the Constitution,” he writes.

His grandson was less politically active and less able to manage money or property, resulting in the need for the sale. It was advertised for weeks in advance in newspapers across the south, Monroe writes, and attracted Northern notice as well. Journalist Mortimer Thomson of the New York Tribune went undercover posing as a buyer to write about the event. His article was eventually published under a pseudonym that’s the only funny thing about this story: Q. K. Philander Doesticks.

But the contents of that article are deadly serious. Writing from a politicized Northern perspective, Thomson still describes the circumstances of the auction with a degree of accuracy. And unlike the plaque erected by the city, he talks about the plight of the individuals whose fates were determined by the sale.

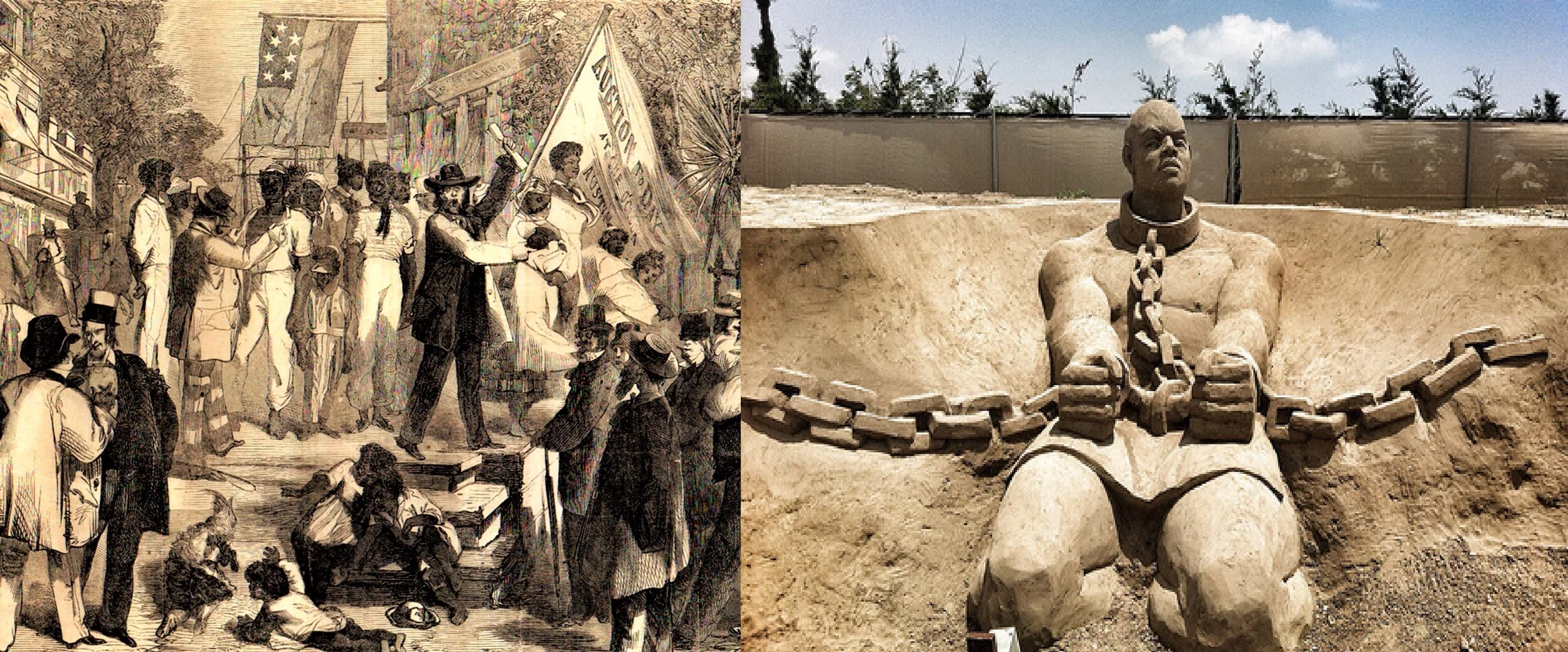

Although a stipulation in the auction was that the enslaved persons had to be sold “in families,” as Thomson discovered, that certainly didn’t mean they were able to stay with the people they wanted to, writes Emory University’s Kwasi DeGraft-Hanson. “Parents were separated from children, and betrothed from each other,” writes DeGraft-Hanson. Brought to the Ten Broeck Race Course on the outskirts of Savannah, and kept in the carriage-stalls, the enslaved men, women and children endured four days of “inspection” by possible buyers before the two-day sale.

“Among the many wrenching stories Doesticks describes is that of a young, enslaved man, Jeffrey, twenty-three years old, who pleaded with his purchaser to also buy Dorcas, his beloved,” he writes. Jeffrey even tries to market Dorcas himself in hopes of convincing the other man to keep them together. “Given the uncertainty of slavery, with is immanence of impending loss and unpredictable futures, Jeffrey felt that his best odds were to help broker his sweetheart’s sale and to suggest her market value,” he writes.

Jeffrey’s purchaser did not buy Dorcas in the end because she was part of a “family” of four slaves who had to be bought together, and the lovers were separated. They certainly weren’t the only ones to suffer this indignity and many others during the two-day auction. A woman named Daphne was also named in Thomson's story. She had given birth only fifteen days previously. She stood on the auction block wrapped only in a shawl. She, her husband, and her two children sold for $2,500.