'Black Swan' | George Balanchine | Battling BMI Beauty in Ballet

/

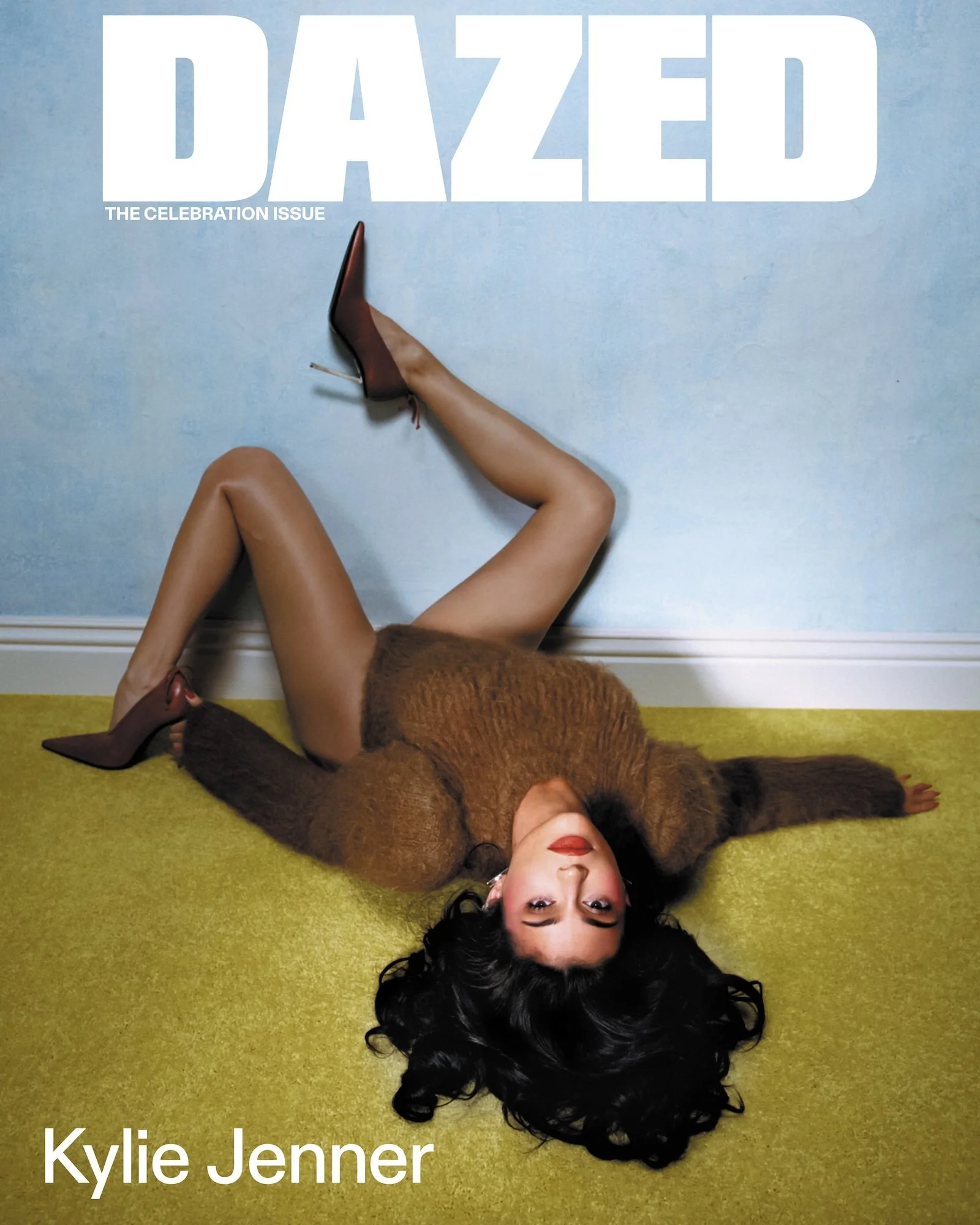

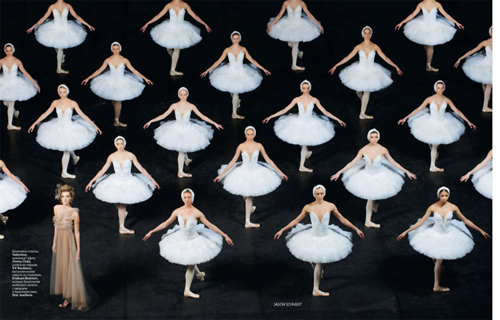

One assumed that Natalie Portman’s ‘Black Swan’ role would inspire magazine editorials like this one of Denisa Dvorakova, lensed by Jason Schmidt for Vogue Russia’s February 2011 issue, styling by Olga Dunina.

Concerns are mounting about the ‘Black Swan’ diet and getting into ‘Black Swan’ shape. Anne has written recently on this topic in our popular Pirelli Defines Sensuality & Fashion Bodies | Arthur Elgort | Karl Lagerfeld.

In May, 2008 The Guardian featured David Kinsella’s documentary that focused on The Kirov Ballet’s size 0 culture, one that requires a BMI of about 14.

A Beautiful Tragedy

Natalie Portman describes the agony she experienced preparing for her role in ‘Black Swan’, one that has garnered her an Academy Award nomination. To prepare for the role, Portman says she literally “starved” herself of food, to the point where some nights, she “literally thought I would die.”

The actress also trained up to 8 hours per day, increasing her body’s need for nourishment.

Our intellectual focus at Anne of Carversville isn’t debating the grueling, self-critical, tortured feet lifestyle that ballerinas go through to become successful. It is their right to do so.

We are focused on why the beauty standard is shrinking in size.

Anne’s years at Victoria’s Secret celebrated size 4-6 supermodels like Naomi Campbell, Stephanie Seymour, Christy Turlington, Cindy Crawford and Claudia Schiffer.

Claudia Schiffer’s 5’11” measurements today are generally estimated at 37-24-35/36 and her bust size is a C-cup. As all the great supermodels remind us, they would be plus-size models today.

Karl Lagerfeld gave Claudia her great start in modeling, and yes, the duo have worked together again these last few years. Lagerfeld now prefers a much thinner woman, as we’ve discussed many times, and she shouldn’t have breasts.

Yes, the Lara Stone love affair and also Crystal Renn’s rise, coupled with the Ralph Lauren photoshop debate, have caused Lagerfeld to soften his fat comments about potato-chip eating mommies.

In her article on the Pirelli Calendar, Anne quotes Lagerfeld extensively on the topic of self-discipline and denial of bodily pleasures.

Historical Evolution of Ballet Bodies

We wonder if the BMI’s of ballet dancers have changed also in the last decades.

It’s seems that before ballet became a nearly monastic disciplline, a more romantic ballet flourished. The public adored Pavlova, who often paid little heed to academic rules, performing with bent knees, bad turnout, misplaced port de bras and incorrectly placed tours.

Reading about Anna Pavlova, one of the greatest dancers in history was called both ‘La petite sauvage’ and ‘The broom’.

Britain’s Dame Margot Fonteyn is estimated by various sources to have had a BMI of 19.2-19.8.

The Balanchine Body

New York City Ballet’s George Ballanchine is credited with creating the current dancer’s body. Balanchine told his dancers that he wanted to “see their bones”. Note that former dancer Toni Bentley defends Balanchine against these charges.

A “Balanchine body” is one with narrow hips, little or no fat deposits, long, lean legs, a short slim torso, small breasts and delicate arms.

In her research paper Behind the Curtain: The Body, Control, and Ballet, Paula T. Kelse writes:

According to a research conducted by Benn and Walters (2001), dancers studied were found to only consume 700 to 900 calories per day. Many of the subjects were consuming less than 700. Surveys conducted in the United States, China, Russia, and Western Europe by Hamilton (1998) found that female dancers’ weights were 10 to 15 percent below the ideal weight for their height. According to the American Psychiatric Association’s official criteria for anorexia nervosa, the number one factor for diagnosis is if the person’s weight is more than 15 percent below the ideal weight for height. This is dangerously close to most dancers! Another factor for diagnosing anorexia nervosa is if the person has developed amenorrhea, that is, if they have missed three consecutive menstrual cycles (Hamilton, 1998). According to Suzanne Gordon’s research (1983), many dancers have ceased menstruating or have many cycle irregularities. Once someone stops menstruating, she may lose 4% of her bone mass annually for the next three to four years (Hamilton, 1998). This causes another set of problems: injury and osteoporosis. If dancers are not consuming enough calories, many times they are nutritionally deficient, which Hamilton (1998) supports in her arguments. If dancers are malnourished and continue to heavily exert themselves through dance, stress fractures, a common injury among dancers, are unavoidable (Hamilton, 1998; Gordon, 1983). Also, osteoporosis is common. One dancer took a bone density test and at 21 years old found she had the bones of a 70 year old (Hamilton, 1998). Dancers are not receiving crucial health and nutrition information, and they may not realize the harm they are inflicting on their bodies until it is too late. Benn and Walter (2001) found that only 18% of current dancers had received proper nutritional education.

Many people believe the myth that female dancers must be skeletal because of the male dancers who have to partner and lift them. This is simply not true. Gordon (1983) interviewed several professional male dancers, who said that they preferred to partner heavier dancers rather than dancers who fit the “anorexic look.” Patrick Bissell, a well-renowned dancer, says that “it’s not easy to partner very thin dancers…they scream out all of a sudden because you pick them up…it makes you very tentative about how you touch them” (Gordon, 1983, p. 151). Another famous dancer, Jeff Gribler, agrees. He says that “It’s easy to bruise a woman when you partner anyway, and if she seems too frail, you don’t want to grip too hard. It can be really painful for her to be partnered” (Gordon, 1983, p. 152). Vane Vest, another dancer, says “these anorexic ballerinas-I can’t bear to touch them…you partner a woman and lift her at the waist and you want to touch something. These skinny ballerinas, it’s awful…how can you do a pas de deux with one of those girls?” (Gordon, 1983, p. 152). Gordon found in her research that ballerinas in Europe and elsewhere weigh more than North American ballerinas, yet male dancers do not seem to have a problem partnering them (Gordon, 1983).

We deliver you back to Jason Schmidt’s editorial of Denisa Dvorakova for Vogue Russia’s February 2011 issue. In our minds, we’re reminded that monitoring and molding the female body by patriarchal forces has gone on for centuries.

Ballet is no different.

Anne is preoccupied with trying to understand why the vision of beauty among women requires them to be smaller and smaller, with vast changes in just 50 years. Is this beauty demand that women shrink in size a response to the second wave of feminism? In our hearts, we believe so.

To be continued …

images via FGR