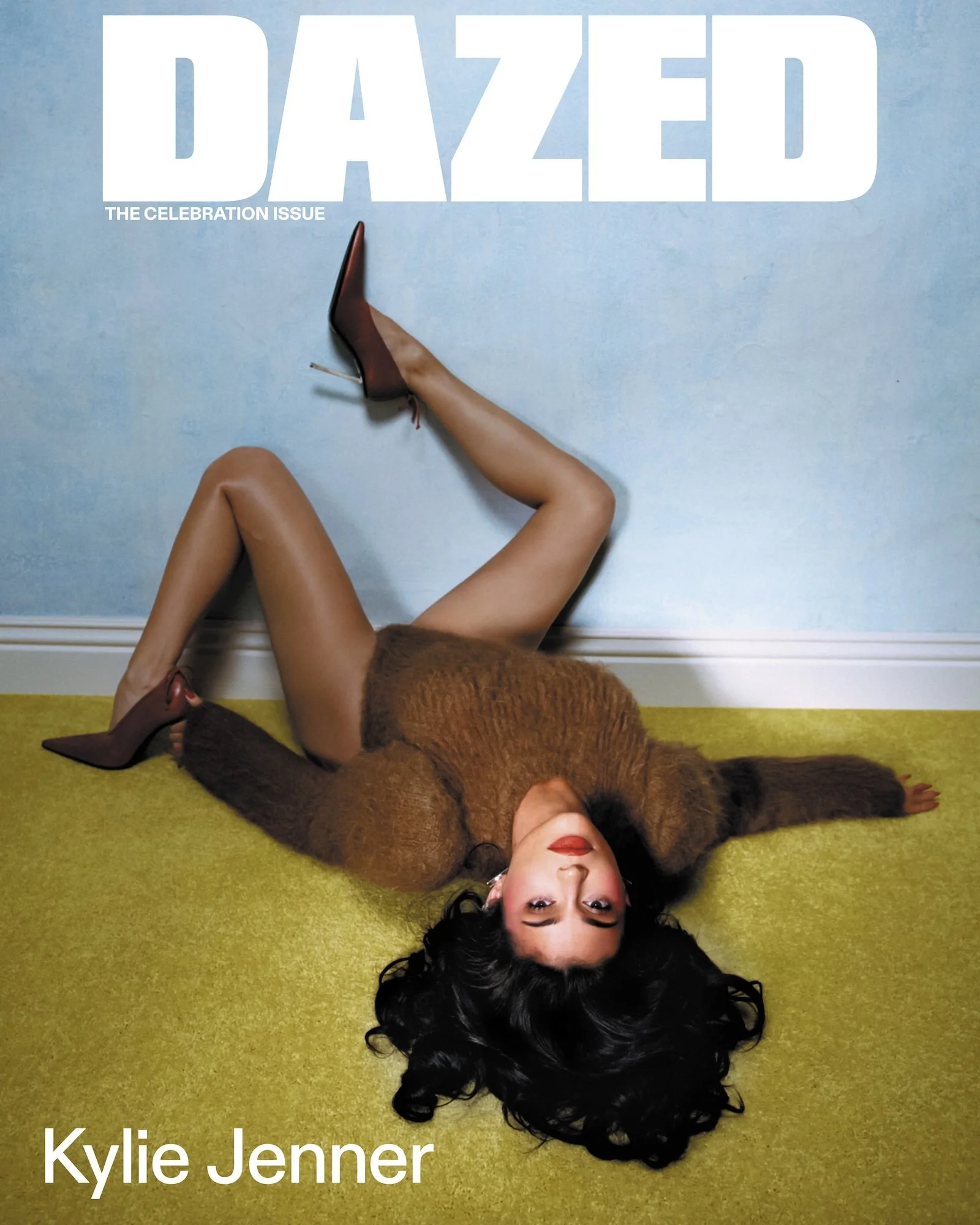

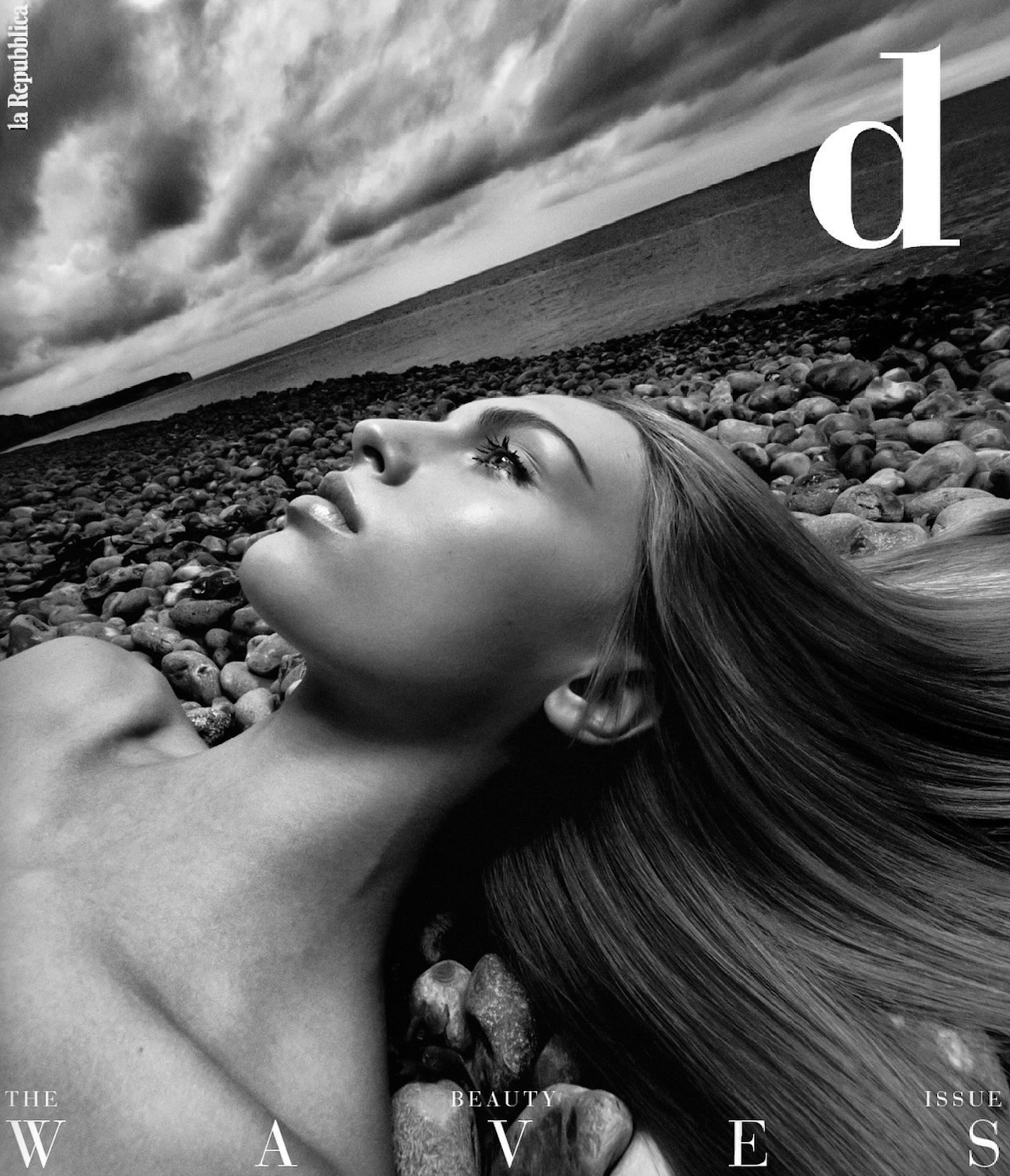

A Brief Art History of Female Sexuality and Flowers Lensed by Alina Gross

/German-Ukrainian photographer Alina Gross [IG] knows that for thousands of years, flowers have been used as divine symbols in art and literature. In other eras of significant censorship, flowers thrived as unspoken symbols of erotism and sensuality.

Gross caught AOC’s attention with her Vogue Portugal June 2024 story with body-paint artist Mia Einat Dan. We also loved Alina’s images shot for Schiaparelli in Spring 2023.

In these lucious images, Aline Gross shares two collections from her ‘Endless Spring’ series, which dovetail with AOC’s desire to discuss flowers as cultural symbols, and particularily as symbols of erotic desire.

The Origins Of Floral Imagery In Ancient Civilizations

In ancient Egypt, the white lotus was considered the original sacred lotus, existing as a transcendent symbol of creation, fertility and rebirth in the continuous cycle of life.

Similarly, in Greek and Roman mythology, goddesses like Aphrodite and Venus were frequently depicted with roses and other flowers, chosen not only to enhance their beauty but also as symbols of divine allure and sexuality.

In India, the Kama Sutra and related texts often employed floral imagery to describe the aesthetic beauty of female anatomy. The intricate descriptions using blossoms like jasmine or the lushness of a blooming lotus invoke a sensual appreciation of the human form, inviting viewers and readers to explore positively the connection between nature and human sexuality.

Chinese poetry and art from ancient dynasties also embraced similar themes, intertwining floral motifs with human beauty and emotion. Flowers populate both the Old and New Testaments with such abundance and diverse meanings that they warrant their own post.

Renaissance Art And Literature: Blossoming Erotic Symbolism

During the Renaissance, a period spanning three evolutions of European culture from 1400 - 1600, European life witnessed a profound revival in art and literature. Writers, poets, and painters began exploring themes of beauty, nature, and human anatomy with increased vigor and creativity. This era witnessed a blossoming of erotic symbolism, where the interplay between human and botanical forms became a prominent artistic signature.

The comparison of female anatomy with flowers can be attributed to the Renaissance's fascination with the natural world, as well as the revival of classical ideals that emphasized beauty and the harmonious proportions of nature. The writings of poets like Petrarch and Shakespeare, William Wordsworth and John Keats, drew upon floral imagery to convey the allure and mystique of the feminine form, while also exploring themes of love and desire.

Renaissance artists sought realism in their depections of all subject matter. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci dissected bodies to understand human anatomy, which influenced their artistic representation of the human form.

Renaissance artists across multiple disciplines moved away from primarily religious subjects and symbols. Nature was often used as a symbol for human emotions and experiences.

Eroticism got a boost in the 18th century, when botanist Carl Linneaus classified the world’s organisms based on the means of reproduction. Linneaus’s Species Plantarum of 1753 gave Latin names to all the known world’s vegetation. Linneaus concluded that plants reproduced sexually, thereby offering a scientific, rational synergy between humans [usually women] and flowers.

The Romantic Era: Sensual Nature And Feminine Allure

During the Romantic Era, which flourished from the late 18th to the mid-19th century, artists were focused on individual experiences and emotions. Prioritizing their own identities, artists sought to express their innermost feelings through their work.

Romantic artists were interested in capturing the sublime, the mysterious, and the irrational, and their works were characterized by a sense of emotion, spontaneity, and passion.

Writers, poets, and painters began to draw parallels between the delicate, unfolding petals of flowers and the sensuality of the female form, creating a rich tapestry of metaphoric language and imagery. Flowers, with their vivid colors, intoxicating scents, and transient nature, served as perfect metaphors for female beauty and sexuality—both alluring and elusive, embodying the intensity and fragility of human emotion.

Poets like William Wordsworth and painters such as John William Waterhouse captured this connection through their work, celebrating the feminine in nature and vice versa.

Romantic artists sought to transcend the mundane and reach deeper truths through the lens of nature, using flowers to express the intimate and the erotic. This era laid the groundwork for later artistic movements, where the sensual and the natural would continue to intertwine in expressions of feminine allure.

Victorian Censorship And Subtle Allusions

During the Victorian era, Britain was characterized by strict codes of morality and rigorous standards of behavior, which often translated into a comprehensive approach to censorship. This period, spanning from 1837 to 1901 during Queen Victoria's reign, was marked by a zealous pursuit of modesty and propriety, reflecting deep-seated societal values and a desire to maintain public decorum. British authorities implemented stringent controls over literature, theater, and art to prevent what was deemed offensive or inappropriate content from reaching audiences.

This desire to uphold certain standards aligned with broader efforts to reinforce social hierarchies and moral norms.

The era saw the rise of institutions such as the Society for the Suppression of Vice and legislation like the Obscene Publications Act, which granted the government powers to seize and destroy works considered obscene. Censorship extended to plays, books, and even newspapers, with content being carefully scrutinized to ensure conformity to moral expectations. The broader intent was to protect society from influences thought to corrupt morals and challenge the status quo.

While Britain's strict approach to censorship was deeply rooted in its societal values and religious sentiments, it also reflected a belief in the moralistic duty of shaping public consciousness. The Victorian ethos prioritized the protection of community standards, often at the expense of personal freedoms, highlighting the complex relationship between moral integrity and cultural expression during this era.

Simultaneously, this period was also marked by a flourishing of creativity in circumnavigating these restrictions.

Writers, poets, and painters began to employ subtle allusions and metaphorical language to explore themes of sensuality and femininity, often using nature as a coded language to depict the female anatomy.

This creative approach allowed artists to probe the mysteries of the body and intimacy without inviting the wrath of strict moral codes or censorship laws. The complexity of flowers—their delicate structures and vivid, organic beauty—offered a rich palette of imagery that could communicate intricate messages of desire and allure.

Petals, stamens, and blossoms became stand-ins for the curves and mysteries of the human form, allowing Victorian creatives to engage in a dialogue about female sexuality within the confines of decorum.

Through such subtle allusions, artists could critique, interpret, and celebrate the human experience, pushing the boundaries of what was considered acceptable and paving the way for more open discussions of human sexuality in the years to come.

Modernist Movements: Breaking Boundaries With Bold Comparisons

During the modernist movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, artists, writers, and poets sought to break away from traditional forms and explore new paradigms of thought and expression. This era was characterized by an experimental approach that pushed boundaries, often delving into subjects previously considered taboo or overly sentimental. It was within this context that comparisons between female anatomy and erotic flowers began to flourish.

Writers like D.H. Lawrence and poets such as Sylvia Plath began to experiment with flowery imagery that encapsulated the rich complexity and beauty of femininity. These comparisons were not merely decorative but laden with meaning, symbolizing both the allure and the inherent mystery of feminine forms.

Painters like Georgia O’Keeffe pushed the envelope with bold depictions that drew parallels between floral shapes and the female body.

It’s noteworthy that O’Keeffe’s painting ‘Jimson Weed / White Flower No. 1’ was sold at Sotheby’s in November 2014 for $44.4 million as the highest auction ever recorded for a female artist. That record still holds today.

Far from mere titillation, their work invited viewers to explore a deeper understanding of nature's eroticism, challenging societal norms about modesty and obscenity. Through these daring comparisons, modernist artists sought to redefine how beauty and desire were represented and understood.

Contemporary Reflections: Evolving Interpretations In Art And Literature

Modern writers and artists explore the flower as a symbol of resilience, empowerment but also contradictions that question the passive connotations previously associated with femininity. This reinterpretation aligns with broader feminist movements that seek to reclaim and redefine female sexuality on their own terms. Artists frequently use floral imagery to evoke a sense of beauty that embraces complexity and imperfection, moving away from idealized notions of womanhood.

Frida Kahlo’s 1943 painting ‘Roots’ sold for $5.62 at Sotheby’s in May 2006. In this case, the visual effects of nature were not erotic but binding — or grounding — with leafy roots and vines growing out of her prone body, then wrapping around her. The painting captures the competing, feminist duality of women’s lives.

Thanks again to Aline Gross for sharing her beautiful, provocative images that prompted me to refresh my own memory about the historical use by artists and creators of flowers and other forms of botany as symbols of the primarily female condition. ~ Anne