Comparing the Cretan and Mediterranean Diets, Dorit Revelis Style in Harper’s Bazaar France June 2025

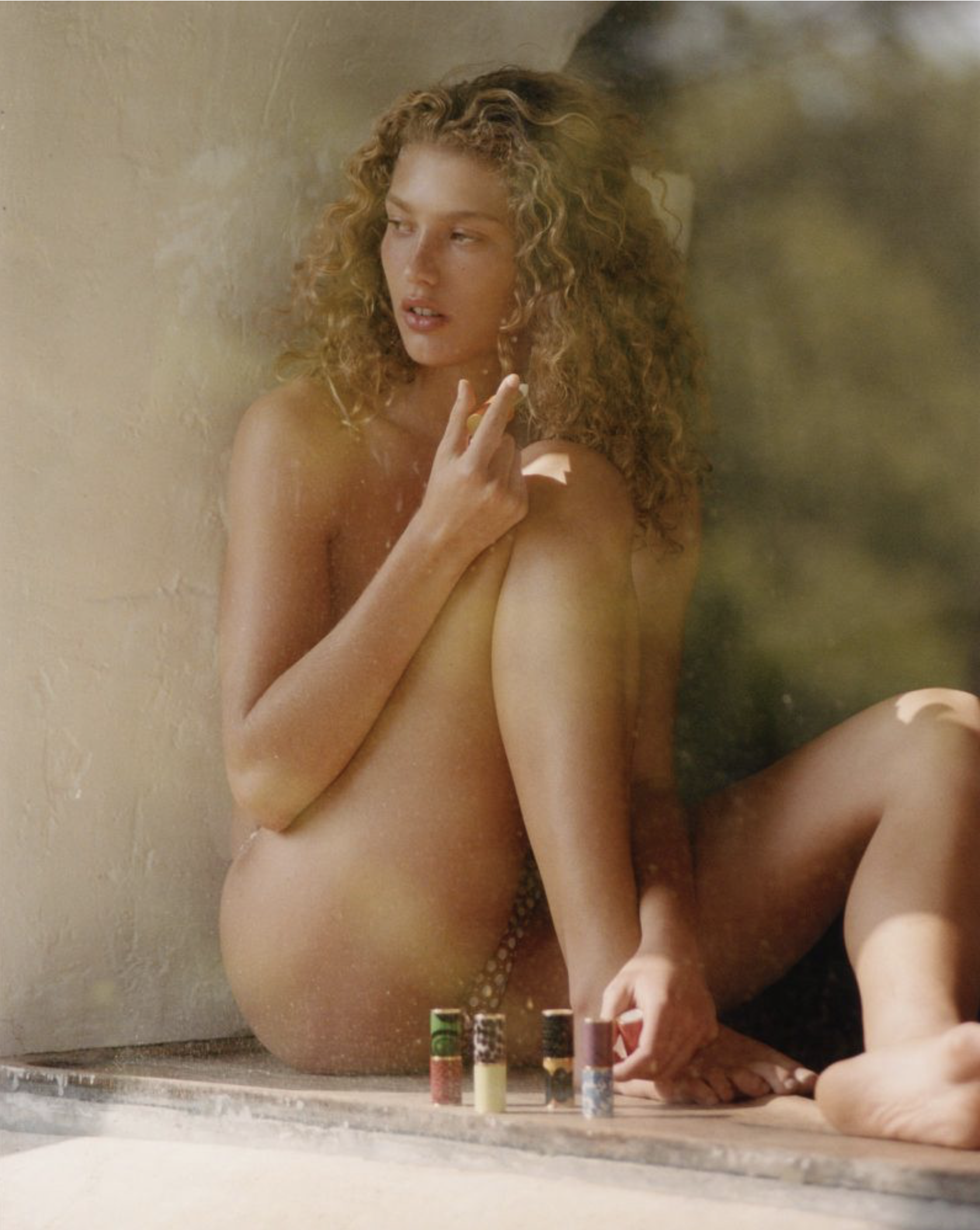

/Israeli model Dorit Revelis is among the most naturally-sensual of our young models; and the beauty industry has embraced her sensual DNA as well. Authenticity is a buzzword of the decade, but Dorit projects a beauty that is both ancient and modern, traits that make it authentic and not contrived.

These images by her ‘love’ Dudi Hasson [IG] for Harper’s Bazaar France [IG] June 2025 issue belong to a beauty story called ‘Le Nouveau Régime Crétois’. Franck Durand provides creative direction with styling by Javier De Pardo. / Makeup by Helene Vasnier; hair by Yuji Okuda; set design by Haleimah Darwish

Crete and The Dawn of Minoan Civilization

The Minoan civilization represents the dawn of Crete's history, flourishing during the Bronze Age from approximately 2600 to 1100 BCE. This civilization, named after the legendary King Minos, is considered Europe's first advanced society, showcasing a high degree of sophistication and complexity. The Minoans developed a remarkable culture characterized by its impressive architectural feats, intricate artworks, and robust trade networks. Central to their civilization were the grand palaces, most notably at Knossos, Phaistos, and Malia, which served as administrative and religious hubs, intricately designed with advanced engineering techniques, including complex plumbing systems and extensive storage facilities.

Around 1450 BCE, the powerful Mycenaean Greeks from mainland Greece began to exert considerable influence over Crete, marking the gradual decline of the once-flourishing Minoan society. This shift was likely accelerated by a series of cataclysmic events, including natural disasters such as earthquakes and the devastating eruption of the Thera volcano.

The volcanic eruption, in particular, severely impacted the Minoans and caused major social disruptions.

The Mycenaeans capitalized on this instability, extending their dominion over Crete and assimilating numerous aspects of its cultural and architectural heritage. They occupied key sites such as Knossos, transforming it into their administrative hub. The Linear B script, an adaptation of the earlier Minoan Linear A used by the Mycenaeans, became prevalent, underlining the depth of Mycenaean control. Despite the Mycenaeans' adoption of various Minoan elements, such as art styles and religious practices, the island saw a marked shift in priorities towards more militaristic and hierarchical societal structures.

Note this distinction, because it will appear in AOC’s commentary about the Mycenean diet.

Over time, the distinctive Minoan civilization faded, absorbed into the broader Mycenaean realm, marking the end of the Minoan era and setting the stage for the subsequent developments in Greek history.

What did not fade was the original Cretan diet lifestyle that helped define the Mediterranean diet.

Eating Fish v Meat in Ancient Crete

The ancient Cretan diet, heavily influenced by the island’s rich olive orchards, vineyards, and proximity to the sea, emphasized olive oil, wine, and a variety of seafood.

Fresh and dried fruits, especially figs and grapes, were staples, as were vegetables such as beans, lentils, and greens gathered from the countryside. The abundance of olives and grapes prominently distinguished the Cretan menu with a distinct emphasis on heart-healthy, plant-based components.

Conversely, the Mycenaean diet on the Greek mainland was characterized by a greater reliance on grain cultivation, reflecting the more expansive agricultural territories found there. Barley, wheat, and millet formed the foundation of their diet, complemented by domesticated livestock such as cattle, sheep, and goats, which provided dairy and meat. Hunting also contributed occasional game to their meals.

Both Cretan and Mycenaean societies shared common elements like bread, olives, and wine but diverged in their reliance on marine versus terrestrial resources. In distinguishing the Cretan diet from the Mediterranean, the lack of meat in original pre-Mycenean daily diet is key.

The Cretan diet was also distinguished by its incorporation of wild greens and herbs, which added essential nutrients and flavors to their meals. Further medical research has determined that often the wild greens were unique to Crete and not available elsewhere in the world. Honey was a primary sweetener, reflecting a diet that relied on natural sources for sweetness.

Influences from trade with ancient civilizations, such as Egypt and the Near East, introduced additional variety, including exotic spices. The combination of local produce and trade influences resulted in a diet that was unique in its emphasis on natural and varied ingredients, contributing to its distinctive place within the ancient Mediterranean dietary landscape.

Militarism and Meat Consumption

AOC has already called out the more militaristic, hierarchical and aristocratic influences that accompanied the Mycenaean conquest of Crete. The customs and mentality of that conquest appear to be deeply rooted in eating meat.

By 1600-1100 BCE in Greece, cattle, pigs, and sheep played a more prominent role in the daily diet, reflecting both pastoral activities and a social emphasis on feasting.

Warrior cultures, such as the Spartans, prioritized meat as a source of power and endurance. Meat, being calorie-dense and protein-rich, was ideal for maintaining soldiers' physical prowess, especially during intense campaigns.

Understanding and explaining accurately the connection between militarism and meat requires further study by AOC.

The Cretan Diet and Longevity

Beginning in the 1950s, Ancel Keys, a physiologist from the University of Minnesota, who was dedicated to learning about and combating heart-related health issues beginning to plague Americans, launched the ‘Seven Countries Study’.

Keys’ seven countries included Finland, Greece, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, United States and Yugoslavia [now Croatia and Serbia]. In launching the study, Keys knew that Finland had a high rate of chronic heart disease [CHD].

Crete was not included in study but Keys knew before launching his research that Crete had an astonishingly low rate of heart disease.

The main conclusions of the study were that animal food groups, with the exception of fish, were strongly positively related to 25-year CHD mortality and that plant food, with the exception of potatoes, were inversely related.

Of the individual foods, butter, hard margarines and meat were most strongly related to CHD mortality rates. The summary factor score was positive [pro CHD] for animal foods and negative for plant foods. This research explained the prestudy facts of astonishingly different rates of CHD between Finland and Crete.

Crete’s Emphasis on Nature-Based Products

In 2025 fake nails or talons have become an outrageous art form that often prevents the easy execution of simple tasks. Some women go so far as to argue that their highly fabricated nails are a political statement, one that translates into “I don’t do housework and definitely not your housework.”

The Cretan approach to nailcare is not driven by political statements. Consider a product like ‘Active glow’, featured above by Harper’s Bazaar France. Active Glow Cranberry is a nail polish from Manucurist that combines nail care and color, using a natural radiance approach.

The all-in-one perfector delivers a tinted glow with a mirror-like shine. With an 83% plant-based formula, it regenerates and nourishes nails, thanks to its blend of cranberry extracts and sweet almond oil. The vegan, made in France product provides nourishment and deep hydration for nails — making it the exact opposite of other very superficial nail art options.

Anne is so intrigued that I just ordered Active Glow cranberry from Amazon for $19 w/free delivery.