Michael Steinhardt, a Leader in Jewish Philanthropy, Is Accused of a Pattern of Sexual Harassment

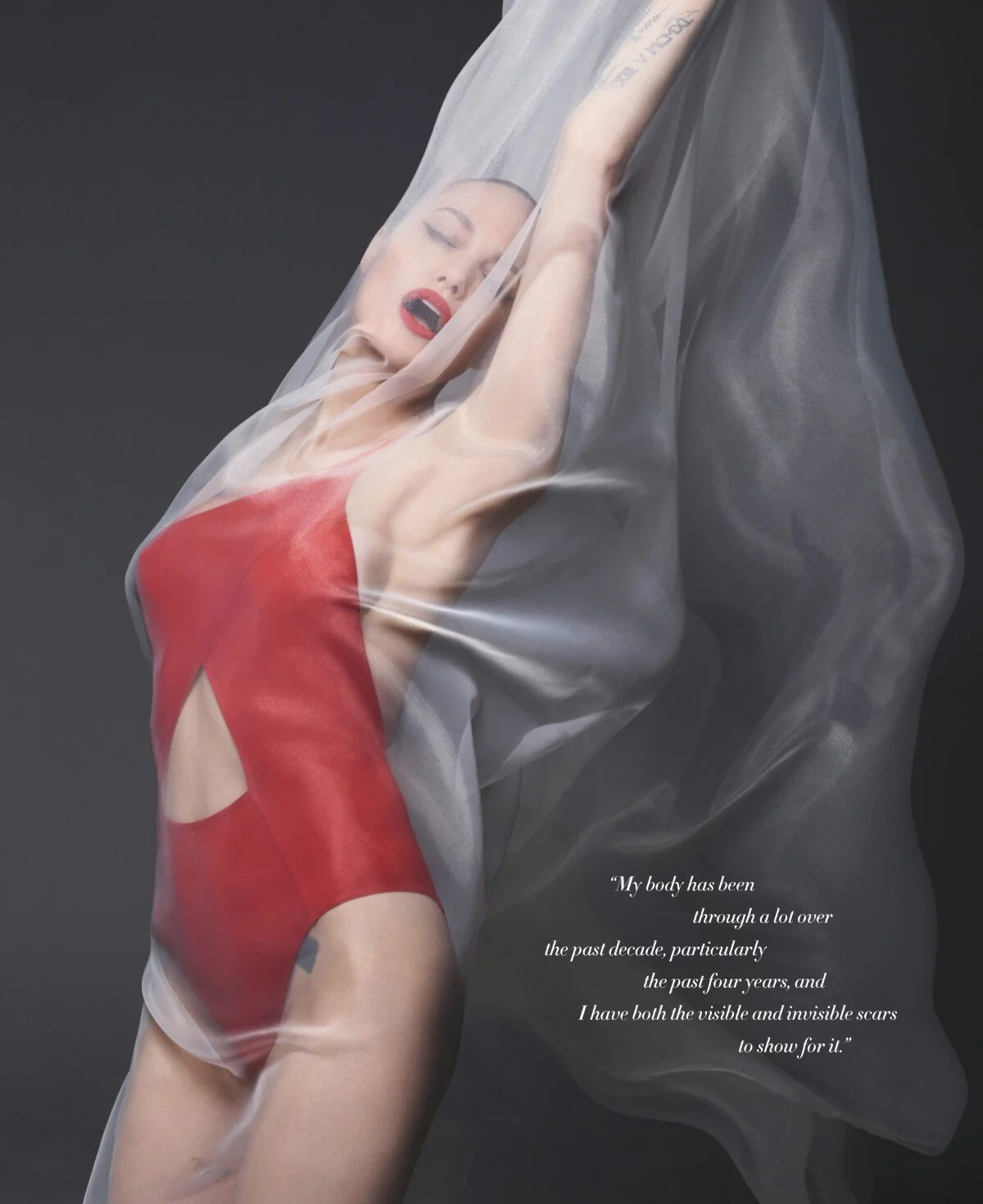

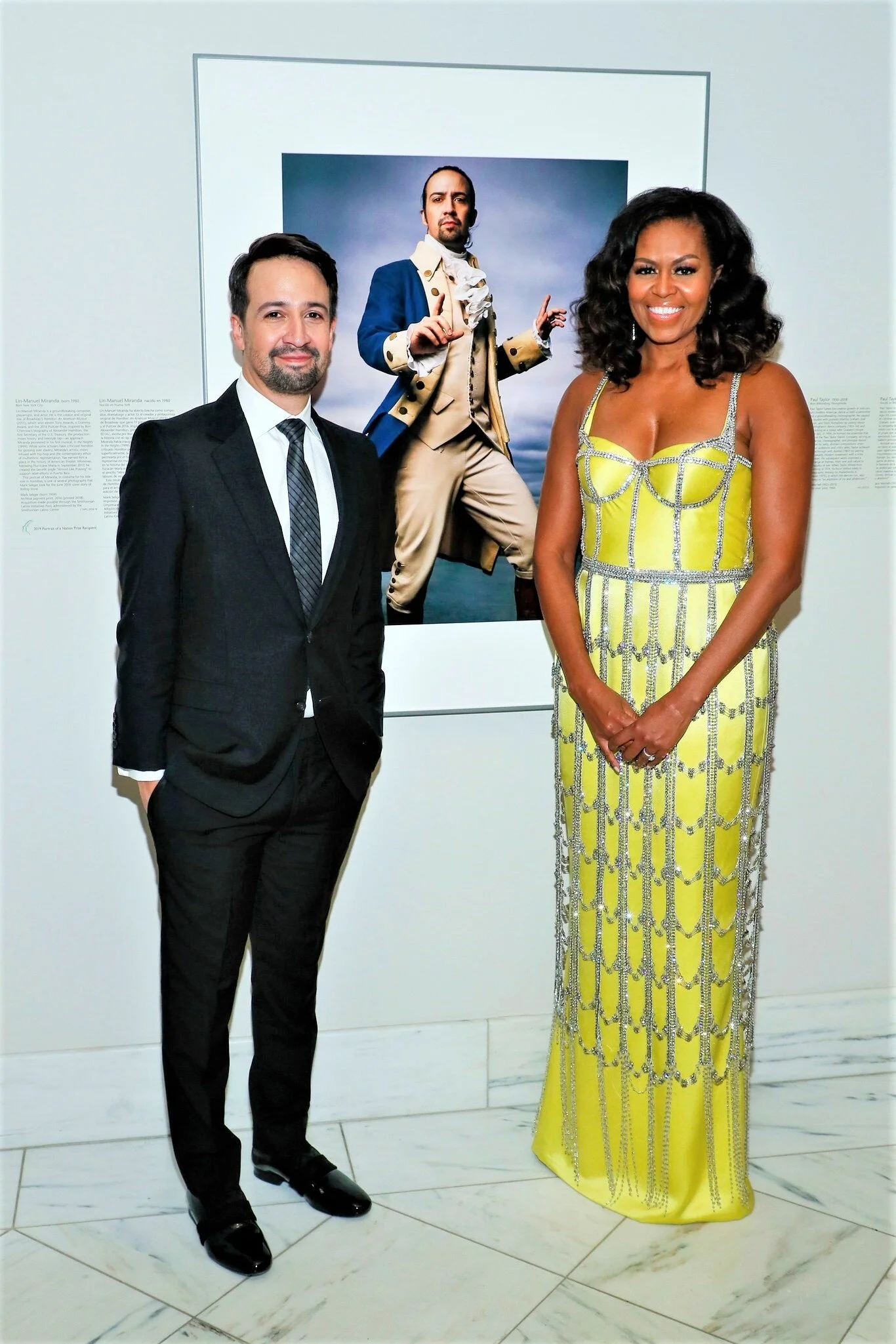

/“Institutions in the Jewish world have long known about his behavior, and they have looked the other way,” said Sheila Katz, a vice president at Hillel International in New York. (Gabriella Demczuk for The New York Times)

By Hannah Dreyfus for ProPublica and Sharon Otterman, The New York Times

Sheila Katz was a young executive at Hillel International, the Jewish college outreach organization, when she was sent to visit the philanthropist Michael H. Steinhardt, a New York billionaire. He had once been a major donor, and her goal was to persuade him to increase his support. But in their first encounter, he asked her repeatedly if she wanted to have sex with him, she said.

Deborah Mohile Goldberg worked for Birthright Israel, a nonprofit co-founded by Steinhardt, when he asked her if she and a female colleague would like to join him in a threesome, she said.

Natalie Goldfein, an officer at a small nonprofit that Steinhardt had helped establish, said he suggested in a meeting that they have babies together.

Steinhardt, 78, a retired hedge fund founder, is among an elite cadre of donors who bankroll some of the country’s most prestigious Jewish nonprofits. His foundations have given at least $127 million to charitable causes since 2003, public filings show.

But for more than two decades, that generosity has come at a price. Six women said in interviews with The New York Times and ProPublica, and one said in a lawsuit, that Steinhardt asked them to have sex with him, or made sexual requests of them, while they were relying on or seeking his support. He also regularly made comments to women about their bodies and their fertility, according to the seven women and 16 other people who said they were present when Steinhardt made such comments.

“Institutions in the Jewish world have long known about his behavior, and they have looked the other way,” said Katz, 35, a vice president at Hillel International. “No one was surprised when I shared that this happened.”

Steinhardt declined to be interviewed for this article. In a statement, he said he regretted that he had made comments in professional settings through the years “that were boorish, disrespectful, and just plain dumb.” Those comments, he said, were always meant humorously.

“In my nearly 80 years on earth, I have never tried to touch any woman or man inappropriately,” Steinhardt said in his statement. Provocative comments, he said, “were part of my schtick since before I had a penny to my name, and I unequivocally meant them in jest. I fully understand why they were inappropriate. I am sorry.”

But through a spokesman, Steinhardt denied many of the specific actions or words attributed to him by the seven women.

A lifelong New Yorker, Steinhardt has given millions to city institutions. NYU Steinhardt is New York University’s largest graduate school, with programs in education, communication and health. There is a Steinhardt conservatory at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, and a Steinhardt gallery at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

But he wields his widest influence in the tight-knit world of Jewish philanthropy.

Along with Charles Bronfman, a billionaire heir to the Seagram liquor fortune, Steinhardt founded Birthright Israel, which has sent more than 600,000 young Jews on free trips to Israel. He spearheaded the creation of a network of Hebrew charter schools. A new natural history museum in Tel Aviv bears his name.

While Steinhardt has been celebrated for his largess, interviews with dozens of people depict a man whose behavior went largely unchecked for years because of his status and wealth.

None of the women interviewed by the Times and ProPublica said Steinhardt touched them inappropriately, but they said they felt pressured to endure demeaning sexual comments and requests out of fear that complaining could damage their organizations or derail their careers. Witnesses to the behavior said nothing or laughed along, women said.

“He set a horrifying standard of what women who work in the Jewish community were expected to endure,” said Rabbi Rachel Sabath Beit-Halachmi, a Jewish scholar. She said that Steinhardt suggested that she become his concubine while he was funding her first rabbinical position in the mid-1990s.

The spokesman, Davidson Goldin, said Steinhardt had never “seriously, credibly” asked anyone for sex.

Michael Steinhardt, a retired hedge fund founder, has donated millions to Jewish nonprofits, New York City institutions and other causes in his career as a philanthropist. (Desiree Navarro/WireImage)

Rabbi Irving Greenberg, who was the president of the Steinhardt Foundation for Jewish Life for a decade, said he repeatedly rebuked Steinhardt for using belittling language toward both men and women. That tension was a factor in his deciding to leave the job in 2007.

Steinhardt could be harsh with men, but his comments to women focused on their appearance and fertility, Greenberg said. When Steinhardt talked to women, the rabbi said, “the implication was that they were not on par with men.”

He said that the comments were made in a bantering, not threatening, tone and that he never saw Steinhardt directly proposition anyone. Still, he said, “I understand that the women felt more shaken or threatened than I recognized at the time.”

Katz said she was hoping Steinhardt would become a funder of her work at Hillel when she met with him in his Fifth Avenue office in 2015 to interview him for a video Hillel had commissioned about Jewish entrepreneurs. But she said that as the filming got underway, he repeatedly asked if she would have sex with the “king of Israel,” which he had told her was his preferred title for the video. He then asked her directly to have sex with him, she said.

When she turned him down, he brought in two male employees and offered a million dollars if she were to marry one of them, she said. After the filming ended, Steinhardt told her it was an “abomination” that a woman who looked like her was not married and said he would not fund her projects until she returned with a husband and child, said Katz, who has not previously spoken publicly about the incident.

Through his spokesman, Steinhardt denied most of the details of Katz’s story and said he did not “proposition” anyone. Goldin said Steinhardt was not aware that Katz was courting him as a donor when they met.

Katz said she was shaken and reported the comments the next day to Eric D. Fingerhut, the chief executive officer of Hillel. He apologized and promised that she would not have to meet with Steinhardt again, she said. Hillel confirmed generally that Katz reported the incident but would not comment on specifics.

Hillel continued to accept donations from Steinhardt until last year, when it hired a law firm to conduct an investigation, according to a person familiar with the matter.

The investigation, which ended in January, concluded that Steinhardt had sexually harassed Katz and another employee in a separate incident. The findings, which were communicated to Hillel staff in an internal memo that did not name Katz or Steinhardt, were first reported in The New York Jewish Week, a community newspaper that has reported on some allegations against Steinhardt.

A Brash Boss. A Big Benefactor.

Steinhardt, who grew up in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, was known for his intelligence and a combative management style when he ran his hedge fund, Steinhardt Partners, which he closed in 1995. In interviews, Steinhardt’s supporters acknowledged he could sometimes be brash and crude, especially when talking about a signature interest: the survival of the Jewish people.

Some of Steinhardt’s most prominent philanthropic efforts are centered on encouraging Jews to marry other Jews and strengthen their ties to the community. He has said his efforts have been driven by the losses of the Holocaust as well as by more contemporary concerns about the effects of intermarriage and secularization.

Steinhardt, who is married with three adult children, is known to goad single Jews into kissing, dating or marrying, and to insist that Jewish women have children, sometimes offering money or the use of a Caribbean home as an incentive, dozens of people said.

“Michael is very passionate, and he is passionate in everything,” Abraham H. Foxman, a longtime friend of Steinhardt’s and the former head of the Anti-Defamation League, said of Steinhardt’s matchmaking. “Call it a passion, call it an obsession, call it a perversion. Some may. I don’t — I understand it. It’s just the way it comes out, which may disturb people.” He said he had never witnessed Steinhardt asking women to have sex and would not expect it of him.

But the behavior described by the women in interviews went well beyond matchmaking.

Goldberg, the director of communications for Birthright from 2001 to 2010, said she was used to Steinhardt being “inappropriate.” Still, she was shocked when Steinhardt suggested that she and a co-worker at a donor reception in Jerusalem join him in an intimate encounter.

Goldberg recalled Steinhardt asking for a threesome; her former colleague, who asked not to be identified, recalled Steinhardt inviting her and Goldberg to leave with him, but did not recall his referring to a threesome.

“We were working Joes, pretty vulnerable, and here he is with all his authority, coming over and propositioning us,” Goldberg, who is now 48, said.

Steinhardt’s spokesman called the account “simply not true.”

Two women who worked at a small Jewish nonprofit recalled Steinhardt using similar language in 2008. They both said that during a meeting at his office to make a pitch for funding, Steinhardt suggested that they all take a bath together, in what he called a “ménage à trois.” One of the women, the executive director of the organization, asked that her identity be withheld because she feared that people on her board would pull their donations if she spoke publicly.

Her former colleague asked that her identity be withheld to protect the executive director.

Steinhardt did not recall this meeting, his spokesman said.

Michael Steinhardt showing anti-Israel, anti-Birthright protesters what he really thinks. Source: Twitter photo capture. via JNS

Goldberg said she believed her encounter took place in 2005. She said that soon after, she shared her account with Shimshon Shoshani, who was then Birthright’s chief executive officer.

Shoshani, who later became the director general of Israel’s Education Ministry and is now retired, said in an interview that he did not recall Goldberg’s allegations. He said he had heard “rumors” that Steinhardt had made inappropriate comments, but said he never heard Steinhardt make such comments.

He praised Steinhardt for his commitment to Birthright. “I appreciate him very, very much. Even if there were some comments, about sex, about women, I wouldn’t take it seriously,” Shoshani said, “because he made important decisions in other areas concerning Birthright.”

Steinhardt has given about $25 million to Birthright, public filings show.

Out of Bounds

While Hillel and Birthright are among the nation’s most well-known Jewish nonprofits, Steinhardt also has given millions of dollars to smaller organizations. Some women who worked at these places described being particularly dependent on his favor.

Goldfein, now 58 and a Chicago-based consultant to nonprofits, said Steinhardt repeatedly made inappropriate comments to her between 2000 and 2002, when she worked as the national program director of Synagogue Transformation and Renewal, a nonprofit he co-founded in 1999 and to which he was giving about $250,000 a year, public filings showed.

Still, she was surprised when, during one meeting at his office to brief him about the organization, he suggested that he could set her up in a Park Avenue apartment and that they could have redheaded babies together, Goldfein said.

She said she felt demeaned by his treatment but tried to make light of the comments because Steinhardt was a director of her organization.

“I always felt that it was like a game to him and that I had to put up with it and play along. But it wasn’t an equal playing field,” Goldfein said. She said his behavior left her disillusioned with the job.

Steinhardt disputed her account. He denied “ever saying anything that was intended to ask anyone to have sex with him,” Goldin said.

After requesting an interview with Steinhardt, the Times received unsolicited praise for his warmth and generosity from former and current employees and some prominent friends, including Bronfman; Martin Peretz, the former owner of The New Republic; and Betsy Gotbaum, the former New York City public advocate.

Some acknowledged his tendency to make bawdy or inappropriate comments, but said Steinhardt was always speaking in jest.

“Michael has his unique sense of humour,” Bronfman wrote. “He loves to tease males and females, and certainly his very good friends. I can attest to that! Always has. But to conjure up intentions that he never had or has is more than a disservice. It’s downright outrageous!”

Shifra Bronznick, a consultant to nonprofits, said she was criticized by her colleagues in 2004 after publicly admonishing Steinhardt for commenting on a woman’s fertility at a conference. She said she believed that his comments were hurting women and their careers in a way that his supporters may not have realized.

“When people say bad things about Jews, our community leaders are on red alert about the dangers of anti-Semitism,” she said. “But when people harass women verbally instead of physically, we are asked to accept that this is the price we have to pay for the philanthropic resources to support our work.”

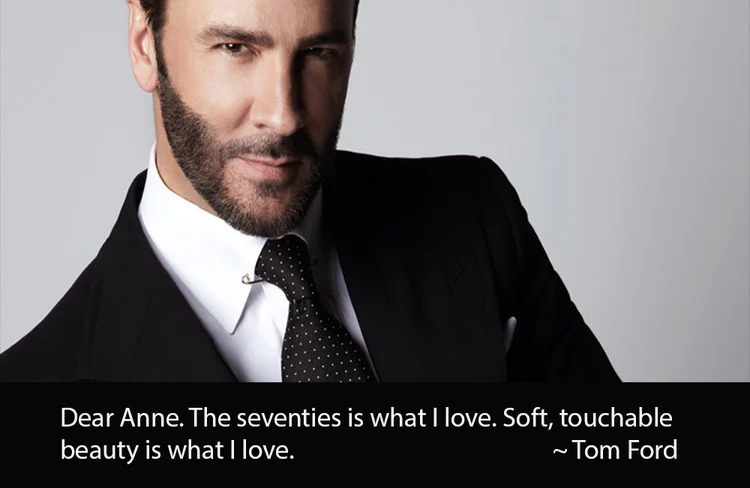

Rabbi Rachel Sabath Beit-Halachmi said she was 27 years old when Mr. Steinhardt, who was funding her first rabbinical position, suggested she should be his concubine.CreditWhitten Sabbatini for The New York Times

Steinhardt’s behavior stretches back to at least the mid-1990s, said Sabath, who recalled visiting him in his office during the 1995-96 academic year as one of the first Steinhardt Fellows at a rabbinical leadership institute.

She was 27 years old, and it was the first time she had met Steinhardt. He harangued her about being unmarried and said she should put her vagina and womb “to work,” Sabath said. He then suggested she become a “pilegesh,” an ancient Hebrew word for concubine, she said.

Taken aback, Sabath said she tried to engage Steinhardt in a discussion about the centuries-old practice of concubinage, which he said should be reinstituted. When an associate of Steinhardt’s walked into the office, Steinhardt told Sabath she should consider having sex with him, she said. Then Steinhardt proposed that she should become his own concubine.

“I have never uttered the word pilegesh, and don’t even know how to pronounce it,” Steinhardt said, through his spokesman. He also denied saying that Sabath should put her vagina and womb “to work.”

Another woman who was a fellow at the institute at the time, Rabbi Dianne Cohler-Esses, said she did not witness that conversation. But she said Steinhardt had separately suggested, in a meeting at his office that year, that she should date a married rabbi at the institute. She said she and Sabath complained to Greenberg about Mr. Steinhardt’s comments.

Greenberg, who at the time was president of the institute, recalled the conversation. He said he told Steinhardt that his behavior was “out of bounds.”

“It doesn’t excuse it and it doesn’t justify it, but I don’t believe that he seriously was recruiting Rachel to be his concubine,” Greenberg said. “It’s typical outlandishness.”

Sabath, who is now 50, went on to become a professor of Jewish thought and director of admissions at the nation’s largest Reform Jewish seminary, Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion. But the experience lingered. For more than two decades, she said, she avoided being in the same room with Steinhardt and could not bring herself to teach about the Torah’s concept of concubines.

She said she did not come forward earlier because she feared for her career and because Steinhardt was a “great benefactor” who supported values in which she believed. “But his being a megafunder can’t allow for, or excuse this behavior, and it has,” Sabath said.

External Scrutiny

None of the six women interviewed by the Times and ProPublica had ever spoken publicly about their experiences, but in recent years, Steinhardt’s behavior has faced some external scrutiny.

Though he was not named as a defendant, he appeared in two sexual harassment lawsuits filed in state court in Manhattan, in 2012 and 2013, against an Upper East Side art gallery.

Two women who worked at the gallery alleged that Steinhardt often made sexually loaded comments to them, which they were expected to endure because he was an important client. Steinhardt is a prominent collector of antiquities.

Steinhardt has been a major benefactor to New York City institutions, including the largest graduate school at New York University. (Gabriela Bhaskar for The New York Times)

Karen Simons, an employee, said in her 2013 lawsuit that in one instance, Steinhardt asked over the phone whether her husband satisfied her and asked her to have sex with him, the suit alleged. In a deposition taken in Simons’ case, Steinhardt said he did not remember making sexual remarks to the two women.

Court documents indicated that Simons’ lawsuit was discontinued in November 2017; the other was settled in 2014. Both suits “were resolved amicably with confidentiality agreements,” said the women’s lawyer, Jeffrey D. Pollack. A lawyer for the gallery, Electrum, which is also known as Phoenix Ancient Art, did not respond to requests for comment.

Goldin, the spokesman for Steinhardt, did not directly address the allegations in the lawsuits, but pointed out that a judge had sanctioned Simons for destroying evidence during the course of her suit. He added that Steinhardt had played no role in the resolution of either case.

Last year, as Hillel International conducted an investigation into Steinhardt’s behavior, the organization did not pursue a $50,000 donation he had pledged, and removed his name from its international board of governors, an advisory board for major donors, according to the person with knowledge of the investigation.

On Jan. 15, lawyers from Cozen O’Connor, the firm conducting the investigation, met with Katz to tell her they had found her complaint against Steinhardt justified, said Debra Katz, Katz’s lawyer, who attended the meeting. She is not related to her client.

The investigators also said a second Hillel employee had come forward during the investigation with a complaint that Steinhardt had made an inappropriate comment to her, Debra Katz said.

Steinhardt apologized “promptly” in 2011 when he found out he had offended this woman, his spokesman said. Steinhardt said in a statement that if he had been told at the time about Katz’s complaint, he would have apologized immediately.

“It pains us greatly that anyone in the Hillel movement could be subjected to any form of harassment,” said the organization’s Jan. 11 memo to employees, signed by Fingerhut and Tina Price, the chairwoman of the board of directors.

Katz, who still works for Hillel, said she decided to speak publicly in part because her role in the Hillel investigation had become known and she feared possible fallout. Her lawyer complained to Hillel in January that people using Katz’s name had called members of its board, upset about the investigation. Hillel declined to comment.

“I want to let other women who went through similar things to know that they are not alone,” Katz said. “And I want organizations, and in particular Jewish organizations who take his money, to consider the impact that’s had on people like me.”

This article is a collaboration between ProPublica and The New York Times. Hannah Dreyfus, who reported this story for ProPublica, is a staff writer for The New York Jewish Week, where she has written about some of the allegations recounted in this story. Sharon Otterman is a reporter for The Times and has covered sexual misconduct in the Roman Catholic church and the Orthodox Jewish community.

Related: Unfairly Pillorying Michael Steinhardt Letter to the Editor New York Times