Supreme Court Says Gerrymandering Fix Up To Voters, Not Judges

/US Supreme Court Justices June 2019 gerrymandering decision: Front row, left to right: Associate Justice Stephen G. Breyer, Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Associate Justice Samuel A. Alito. Back row: Associate Justice Neil M. Gorsuch, Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Associate Justice Elena Kagan, Associate Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh.. Credit: Fred Schilling, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

By John Rennie Short, Professor, School of Public Policy, University of Maryland, Baltimore County. First published on The Conversation.

In a 5-4 decision the Supreme Court has ruled that partisan gerrymandering is not unconstitutional.

The majority ruled that gerrymandering is outside the scope and power of the federal courts to adjudicate. The issue is a political one, according to the court, not a legal one.

“Excessive partisanship in districting leads to results that reasonably seem unjust,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts in the majority decision. “But the fact that such gerrymandering is incompatible with democratic principles does not mean that the solution lies with the federal judiciary.”

So for now, partisan gerrymandering, in which politicians get to choose their voters rather than voters choose their representatives, will remain a fact of American political life.

What is the background to this decision? And what does the decision mean for democracy in the U.S.?

Cracking and Packing

State legislatures have the constitutional responsibility to draw up the boundaries of congressional seats after the results of the census, which is conducted every 10 years.

In many states, if one party is in the majority at that time, they can use their power to manipulate the boundaries to their advantage. That’s called partisan gerrymandering, and it involves what’s referred to as “cracking and packing.”

Cracking spreads opposition voters thinly across many districts to dilute their power. Packing concentrates opposition voters in fewer districts to reduce the number of seats they can win.

Just one example: In 2012, Republicans in Ohio drew up congressional boundaries that packed most Democratic voters into just four of the 16 congressional districts. The 9th District was referred to as the “snake on the lake” as it slithered along the edge of Lake Erie from Cleveland to Toledo to pack in as many Democratic voters as possible.

The gerrymandered 9th Ohio US Congressional District, known as ‘the snake on the lake.’ US Department of the Interior via Wikipedia

It worked. In the 2018 election, Ohio Republicans won just 52% of the votes but picked up 11 of 16 of the congressional seats.

I have researched the U.S. voting system, analyzed Supreme Court rulings and shown why gerrymandering is now more prevalent since the 1990s. Sophisticated computer programs and ever more detailed information on voters’ location and preferences now allow politicians to crack and pack with surgical precision.

In 2004, the Supreme Court effectively sanctioned gerrymandering. In Vieth v. Jubelirer, the court ruled 5-4 not to intervene in a case brought by Democrats in Pennsylvania over a redistricting plan they claimed was unconstitutionally gerrymandered.

After the ruling, partisan gerrymandering increased, especially in the redistricting round after the 2010 census.

In 2017, and again in 2018, the Supreme Court passed up opportunities to decide upon the constitutional legality of gerrymandering by effectively punting on the cases.

In other cases, the court actively intervened.

Republican-controlled Shelby County, Alabama filed a case against the constitutionality of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. The act had protected minority voters’ rights in the South from being diluted by gerrymandering and other methods. In the 2013 case Shelby v. Holder, the court overturned key elements of the act, in a 5-4 ruling. The ruling encouraged partisan gerrymandering in the states – Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina and Virginia – previously under federal scrutiny for their legacy of discriminatory voting practices.

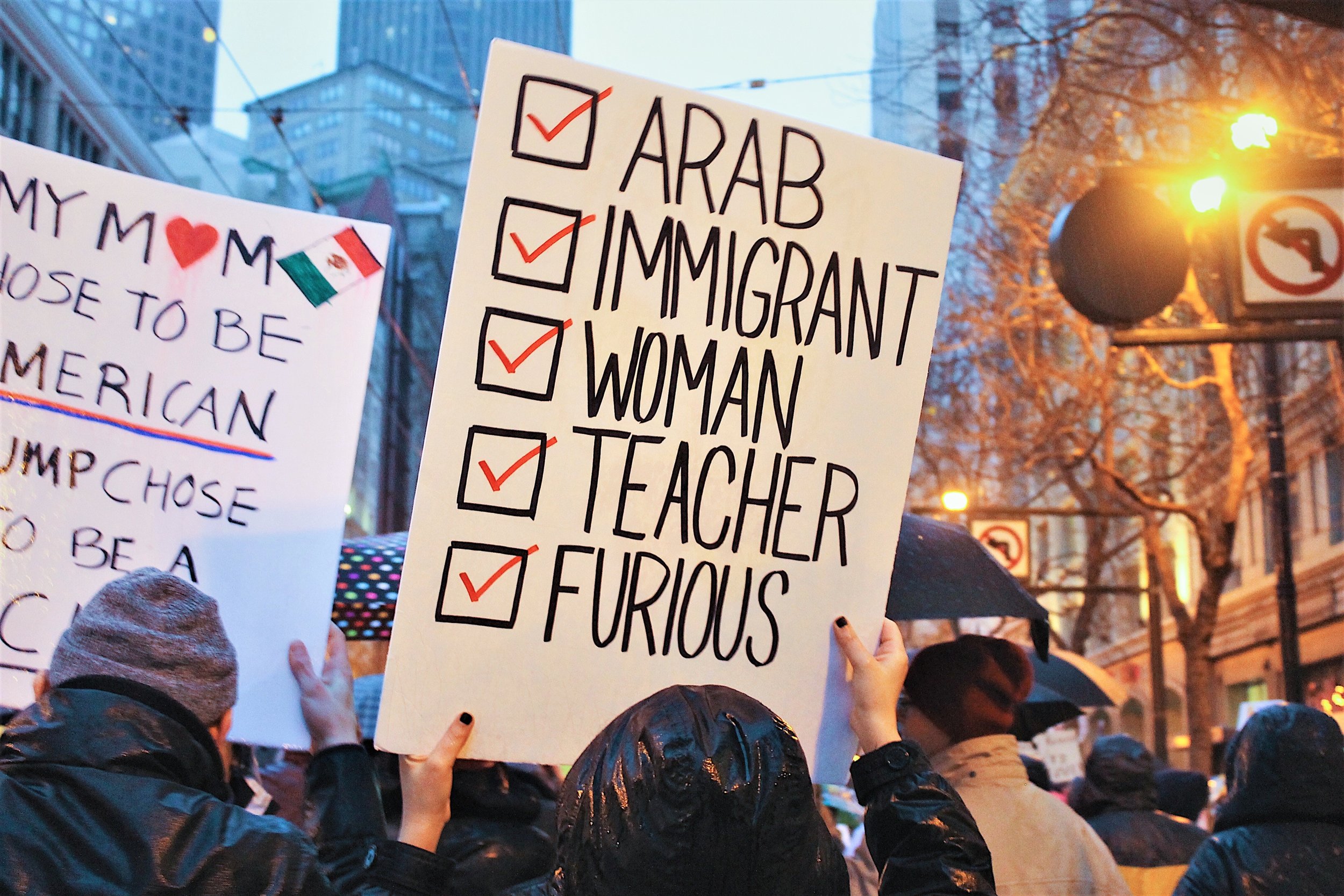

Photo by Elliott Stallion on Unsplash

Mounting Legal Challenges

There have been other legal challenges to partisan gerrymandering.

In Virginia a Republican map drawn up in 2011 that packed many African American voters into just 11 of the state’s 100 House of Delegates districts was challenged. A federal judge saw racial gerrymandering at work and ordered a new map. A Republican challenge to that ruling came before the Supreme Court. The Republican challenge was dismissed on June 17, 2019.

The court’s decision in the Virginia case was not about whether the gerrymandering was unconstitutional. Instead, a 5-4 majority of the court ruled that the Virginia Republicans had no legal standing to mount the appeal when the state senate and the state attorney general had decided against appealing. The new map stood.

In Ohio, a three-judge federal panel ruled that the Republicans attempted to cement a Republican majority of congressional seats when they drew up new districts. The state legislature was ordered by the court to draw a new map for the 2020 election.

And in Michigan a panel of federal judges ruled that many of the state’s legislature districts were unconstitutional, drawn up to ensure a partisan advantage. No more snake on the lake.

The Supreme Court set aside these last two lower court rulings on May 24, 2019 in preparation for this recent decision. The two cases are now sent back to lower courts for dismissal. The snake on the lake lives on for another election cycle.

Maryland and North Carolina

Gerrymandering is especially rampant in Maryland and North Carolina. In both states powerful politicians admitted that their plan was to solidify their party’s control.

Republicans in North Carolina drew a map in 2016 to ensure control of 10 of the state’s 13 congressional districts. Democratic voters were overwhelmingly packed into three districts with the remainder cracked across the remaining 10.

Democrats in Maryland drew a map with gyrating boundaries in order to cement their 7-1 advantage in congressional seats.

When lower federal courts struck down these gerrymandered congressional district maps, politicians in both states appealed to the Supreme Court.

Arguments were heard on these cases in March 2019.

From the questioning, it appeared that the liberal justices – Breyer, Ginsburg, Kagan and Sotomayor – would rule against gerrymandering and the more conservative justices – Roberts, Alito, Thomas and Gorsuch and Kavanaugh – were against the court getting involved.

The votes predictably split along the ideological divide.

In the majority opinion, combining the Maryland and North Carolina cases into one decision, the court’s conservative majority noted that existing measures of gerrymandering do not provide precise and judicially discernible standards. The opinion was authored by Chief Justice Roberts, who has long held the opinion that it is impossible to measure, let alone overcome, partisan gerrymandering.

Responding for the liberal minority, Justice Kagan read her dissent in open court – a sign of her intense disagreement with what she saw as the court’s unwillingness to uphold fair and free elections. She wrote that the decision “debased and dishonored our democracy.”

Now what?

Partisan gerrymandering will continue. But so will resistance against it, I believe.

There is a way for states to avoid gerrymandering. Newly formed, nonpartisan redistricting commissions, working outside the influence of the legislature to draw legislative district lines, already exist in Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Michigan, Montana and Washington.

These commissions resulted from citizen initiatives to reform the process. But most states east of the Mississippi, for instance, do not have a ballot initiative process that would allow voters to initiate reform.

Gerrymandering has a pernicious impact on the electoral system and on the wider democratic process. It encourages long-term incumbency and a consequent polarization of political discourse.

But now the Supreme Court has made it clear that the solution does not lie with federal judges.

It is up to the voters.