3 New Books | Diane Arbus Life and Images 40 Years Later

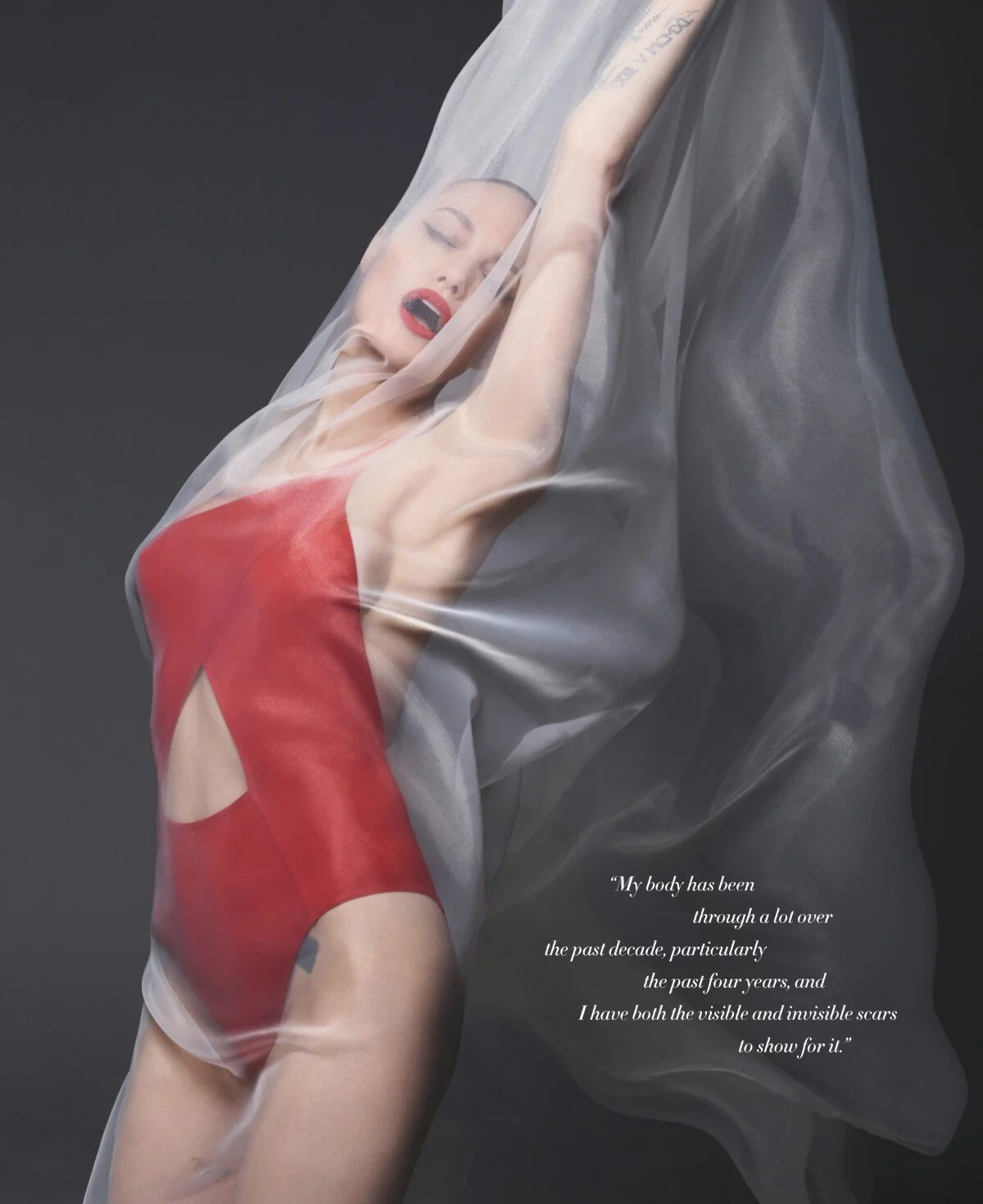

/ Diane Arbus self portrait w/daughter Doon

Diane Arbus self portrait w/daughter Doon

On the 40th anniversary of her suicide this fall, Diane Arbus is front and center in the photography world.

Diane (pronounced Dee-Ann) Arbus was one of the most revered photographers in the history of American art. Her unsettling portraits, in stark black and white, seemed to reveal certain psychological truths of their subjects and humanity in general.

Whether Arbus was a humanist or nihilist has been the subject of much debate since her death.

After Arbus followed the path of Sylvia Plath, committing suicide in 1971, at the age of forty-eight, her own seemingly chaotic and dark inner life became inextricable from her work for many viewers of her work.

Written in the spirit of Janet Malcolm’s classic examination of Sylvia Plath, The Silent Woman, William Todd Schultz’s An Emergency in Slow Motion digs deeply into the creative and personal struggles of Diane Arbus.

William Todd Schultz is now a professor of psychology at Pacific University in Portland, Oregon, specializing in personality research and ‘psychobiography.’

It’s within this genre that the author tries to make sense of what he terms Arbus’s “oceanic” personality. Schultz does so without the cooperation of Arbus’ estate who seeks to have her art speak for itself without the psychoanalysis.

Schultz examines Arbus’s life through the prism of four central mysteries: her outcast affinity, her sexuality, the secrets she kept and shared, and her suicide.

He seeks not to diagnose Arbus, but to discern some of the private motives behind her public works and acts. In this approach, Schultz not only goes deeper into Arbus’s life than any previous writer, but provides a template with which to think about the creative life in general.

Two more new books shed light on the images of Diane Arbus.

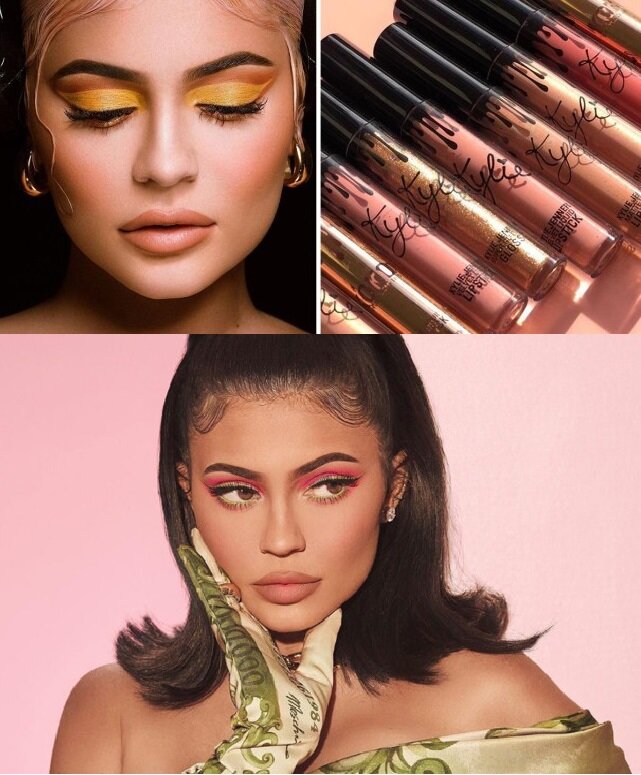

Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph

Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph: Fortieth-Anniversary Edition was originally published in 1972, one year after the artist’s death. The book was published in conjunction with a retrospective of her work at the Museum of Modern Art. Edited and designed by Arbus’s daughter, Doon, and her friend and colleague, painter Marvin Israel, the monograph contains eighty of her most masterful and well-known photos.

Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph: Fortieth-Anniversary Edition was originally published in 1972, one year after the artist’s death. The book was published in conjunction with a retrospective of her work at the Museum of Modern Art. Edited and designed by Arbus’s daughter, Doon, and her friend and colleague, painter Marvin Israel, the monograph contains eighty of her most masterful and well-known photos.

The images in this newly published edition, marking the twenty-fifth anniversary of the collection’s original publication, were printed from new three-hundred-line-screen duotone film, allowing for startlingly clear reproduction. The impact of the collection is heightened by the introduction, which contains excerpts of audio tapes in which Arbus discusses her experiences as a photographer and her feelings about the often bizarre nature of her subjects. Diane Arbus’s work has indelibly impacted modern visual sensibilities, evidenced by the intensely personal moments captured in this powerful group of photographs.

Diane Arbus: Untitled

Diane Arbus: Untitled is devoted to images taken between 1969 and 1971, when Diane Arbus focused her lens on residents in homes for the mentally retarded. Diane Arbus’ daughter Doon writes that her mother’s photographs remind “us that facts lie at the root of what we’re looking at,” yet it takes us a moment to realize or even come to terms with those facts.

Morality and the Diane Arbus Gaze

Even an ‘average’ or ‘normal’ person looks off-kilter in Arbus’ lens, as if her camera becomes both a voyeuristic keyhole and also a great leveler or democratic instrument. Arbus images, jarring yet magical, arrive from the past to give a lyrical poke at our collective subconscious, to wake us up—and remind us to look, writes Raul Nino in an out of print version of ‘Diane Arbus: Untitled’.

We confront our own shame, our prejudices and the challenges to our own preconceived vision of orderly reality. Susan Sontag wrote scathingly of Diane Arbus’ style of showing us “people who are pathetic, pitiable, as well as repulsive”.

Diane Arbus 1949In perhaps the most angry essay in her book On Photography, Sontag insists that Arbus’s gaze is “based on distance, on privilege, on a feeling that what the viewer is asked to look at is really other”.

Diane Arbus 1949In perhaps the most angry essay in her book On Photography, Sontag insists that Arbus’s gaze is “based on distance, on privilege, on a feeling that what the viewer is asked to look at is really other”.

Sandra S Philips, curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco, told the Smithsonian magazine in 2004. “To cast Arbus in the role of a tragic figure who identified with ‘freaks’ is to trivialise her accomplishment … She was a great humanist photographer who was at the forefront of a new kind of photographic art.”

Talking about growing up in the Depression as a privileged child, Arbus told Studs Terkel “I grew up feeling immune and exempt from circumstance. One of the things I suffered from was that I never felt adversity. I was confirmed in a sense of unreality.”

Arbus’ photos are so undeniable in their effect that, even when the response is approving, it’s expressed in similarly troubled terms. Janet Malcolm, whose The Journalist and the Murderer is the definitive meditation on the parasitic relationship between an artist and her subject, describes Arbus, in Diana & Nikon , as “a straight woman from a rich Jewish family that made its money in fur [who] has penetrated a sordid closed world and, through her journalist’s too-niceness, become privy to its exciting and pathetic secrets.”

Thurman writes that Diane Arbus was ‘nubile’ and captivating, possessed with an inescapable sexual charge.

In today’s world where all have a camera and being a ‘photographer’ is a calling for many, the words of Douglas Davis, written in Newsweek 1984 resonate.

“I have never seen pictured like them before, and I am sure I will never see their equal again. They are the product of something beyond the camera, the result of a long, complex and intensely human process. No one can go into the street tomorrow and take a Diane Arbus photograph. That would be merely adjusting a lens and pressing a button. What made her pictures great was everything that happened before she pressed the button.”

Diane Arbus biography Jewish Virtual Library