Camp Explained In Gucci's Pre-Fall 2019 Ad Campaign In Advance Of May 6 Met Gala + Art Exhibit

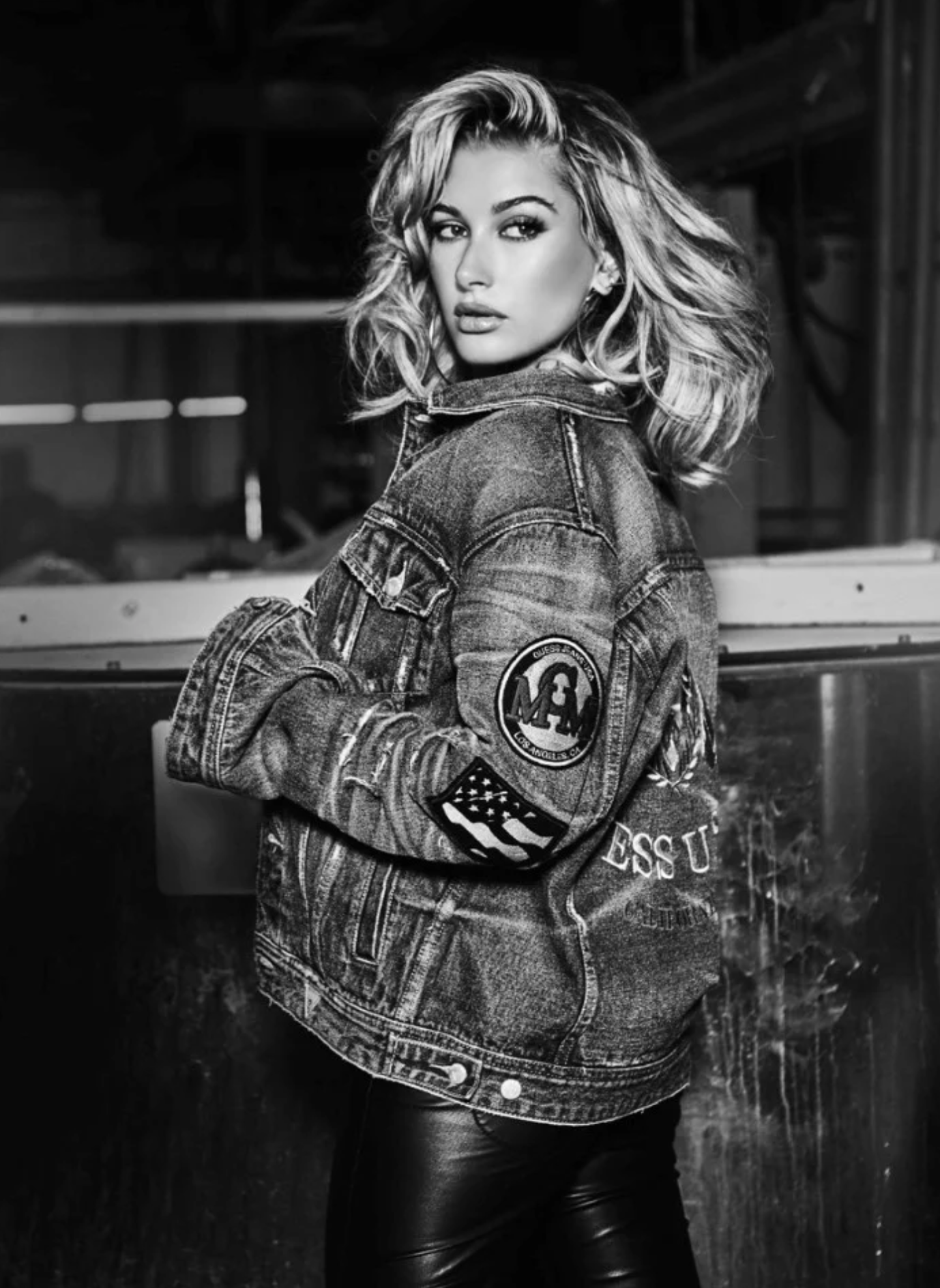

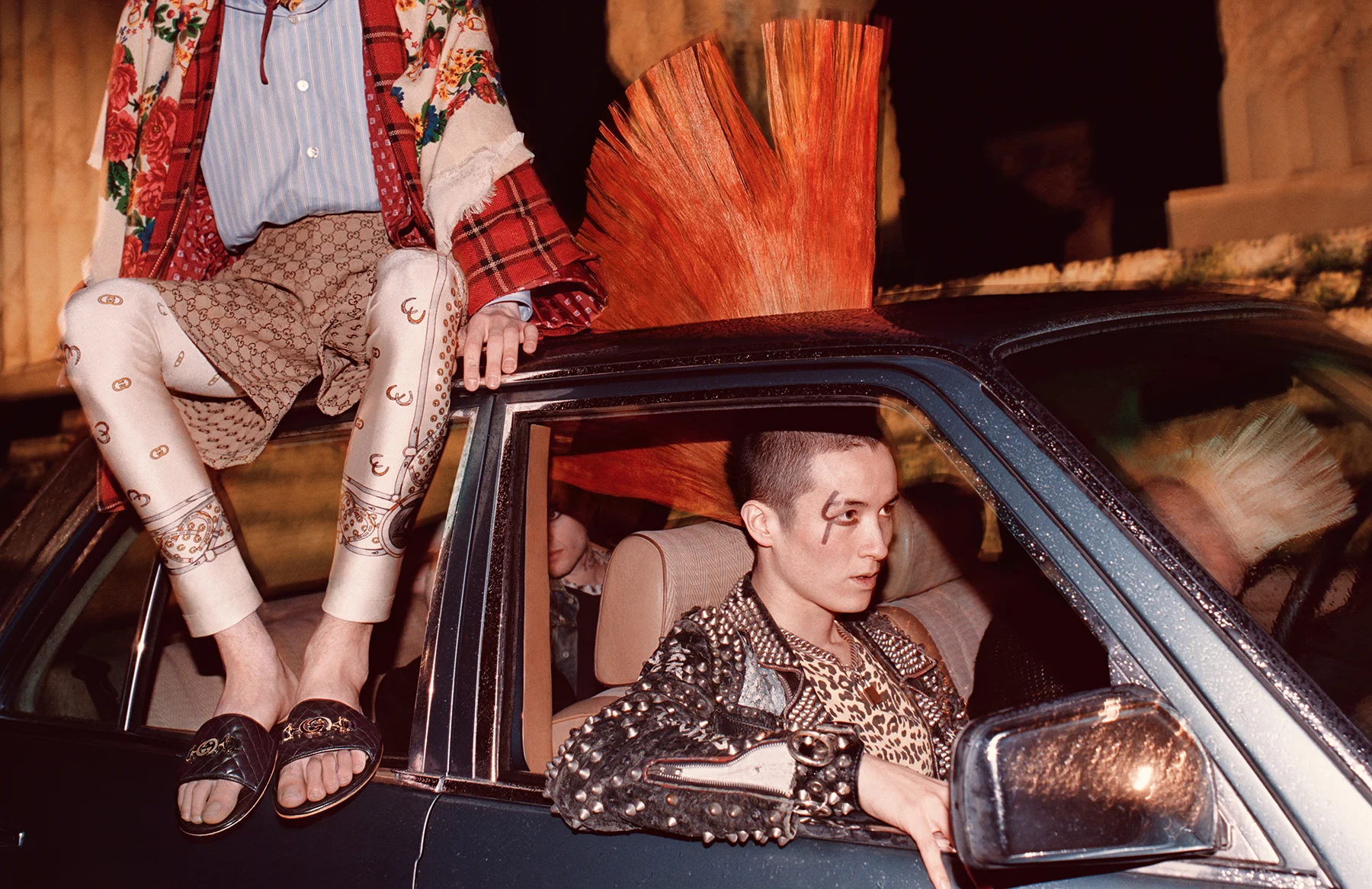

/Photographer Glen Luchford shoots Gucci’s pre-fall 2019 ad campaign, continuing with the brand’s wildly successful camp approach to fashion under creative director Alessandro Michele. Jonathan Kaye styles models Delphi Mcnicol, Dwight Hoogendijk, Emmanuel Adjaye, Matïss Rucko, Matthew Petersen, Paul Hendrik Piho, Unia Pakhomova, Walter Pearce, and William Valente against the backdrop of old-world Italian traditions.

In advance of the Gucci-sponsored May 6 Met Gala in New York, Alessandro Michele has explained that ‘Camp: Notes on Fashion’, open to the public May 9 through September 8, 2019, is inspired by Susan Sontag’s seminal 1964 essay ‘Notes on Camp’. Sontag’s essay “perfectly expresses what camp truly means to me: the unique ability of combining high art and pop culture.”

Andrew Bolton, Wendy Yu Curator in Charge of the Costume Institute explains camp’s core elements that include “irony, humor, parody, pastiche, artifice, theatricality, excess, extravagance, nostalgia, and exaggeration”—all of which can, by turns, be discovered in Michele’s playful Gucci oeuvre.

Sontag argued that camp is the “love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration . . . style at the expense of content . . . the triumph of the epicene style”. For Bolton and Michele, Sontag’s vision has enormous resonance at this moment in our cultural and political affairs.

Camp, as Bolton notes, “has become increasingly more mainstream in its pluralities—political camp, queer camp, Pop camp, the conflation of high and low, the idea that there is no such thing as originality.” Camp, he continues, has been described as style without content. “But I think you’ve got to be incredibly sophisticated to understand camp—look at Yves Saint Laurent and Marc Jacobs.”

Bolton has traced the origins of camp back to the French verb se camper meaning to strike an exaggerated pose, and its origins in the flamboyant posturing of the French court under Louis XIV. Artsy speculates that ‘camp’ is derived from K.A.M.P., which stood for “Known As Male Prostitute.”

In AOC’s opinion, one can’t think of camp without considering the golden palace apartment of Donald Trump, sitting atop Trump Tower in Manhattan, about 30 blocks south of the Met. Trump himself is a cariacture in the world of camp. He admits to fashioning his Trump Tower apartment and Mar-a-Lago in South Beach, inspired by the flamboyant posturing of the French court under Louis XIV.

Artsy writer Jackson Arn suggests that ‘camp’ “is now applied to everything under the sun”, with the result that the concept of camp is no longer subversive because all the meaning has been squeezed out of it.

Alessandro Michele’s wildly-successful vision for Gucci, reflected in his ad campaigns and fashion shows, seem to reflect his understanding of camp in this Trumpian moment. But he’s also playing a role in emptying camp of its subversive quality by making it mainstream and influential as the key ingredient in the Gucci brand’s DNA.

Within this watered-down vision of camp, it’s easy to understand the collision of camp with American outrage over both Gucci’s and Prada’s blackface cultural moments. Blackface originated in America and quickly became popular in Europe, but it became largely taboo in America after the civil rights movement. In fact, Wikipedia has a heavily-annotated list of resources on this subject for further reading.

Alessandro Michele easily taps into the sexual history of camp, including its roots in crossdressing and gender fluidity.

For Bolton, the first mention of camp appears to have been in a letter dated 1869, sent by Lord Arthur Clinton to his lover Frederick Park, a cross-dresser known as Fanny. “My campish undertakings are not at present meeting with the success they deserve,” Lord Clinton notes. “Whatever I do seems to get me into hot water.” Fanny and his partner in cross-dressing, Ernest Bolton (known as Stella), were indeed sent to the courts for gross indecency but ultimately cleared of wrongdoing, to the delight of the crowds. Their story—documented in Neil McKenna’s riveting 2013 book Fanny and Stella—inspired Erdem Moralioglu so much that he based his recent Spring 2019 collection on them, including trans beauties in his runway casting.

Bolton concludes his Vogue interview on a roll, trying in earnest to help us understand camp. “Chanel was camp as a person but her clothes weren’t camp,” he explains, “whereas Schiaparelli was camp as a person and so were her clothes. You end up seeing camp everywhere!”