Bazaar Arabia Goes to Marrakech, A Key Location on the Map of New Humanism

/The Marrakech markets are labyrinths filled with rich textures and time-honoured traditions, blended with new seasonal standouts that tell a story shaped by centuries…

With this greeting, the December 2025 issue of Harper’s Bazaar Arabia [IG] brings us to Marrakech, a very important place in the history of the world and a treasured place in my own heart. If I close my eyes, I can still fell the cool breeze of evening caressing my face, as my partner and I surveyed this magic place from a carpet-laden roof top complete with a soulful sounds jazz quintet. It was the first of many nights to remember about Marrakech.

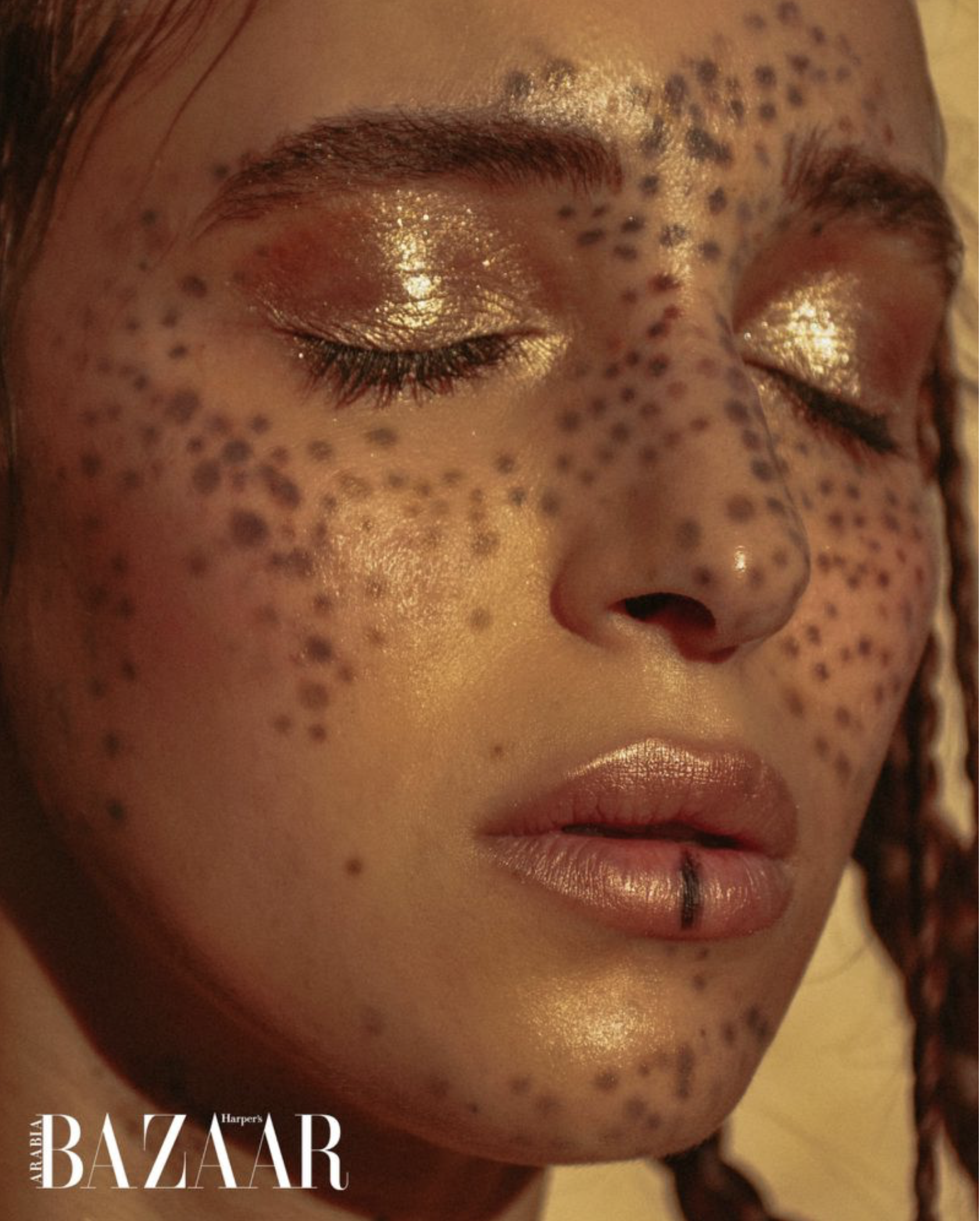

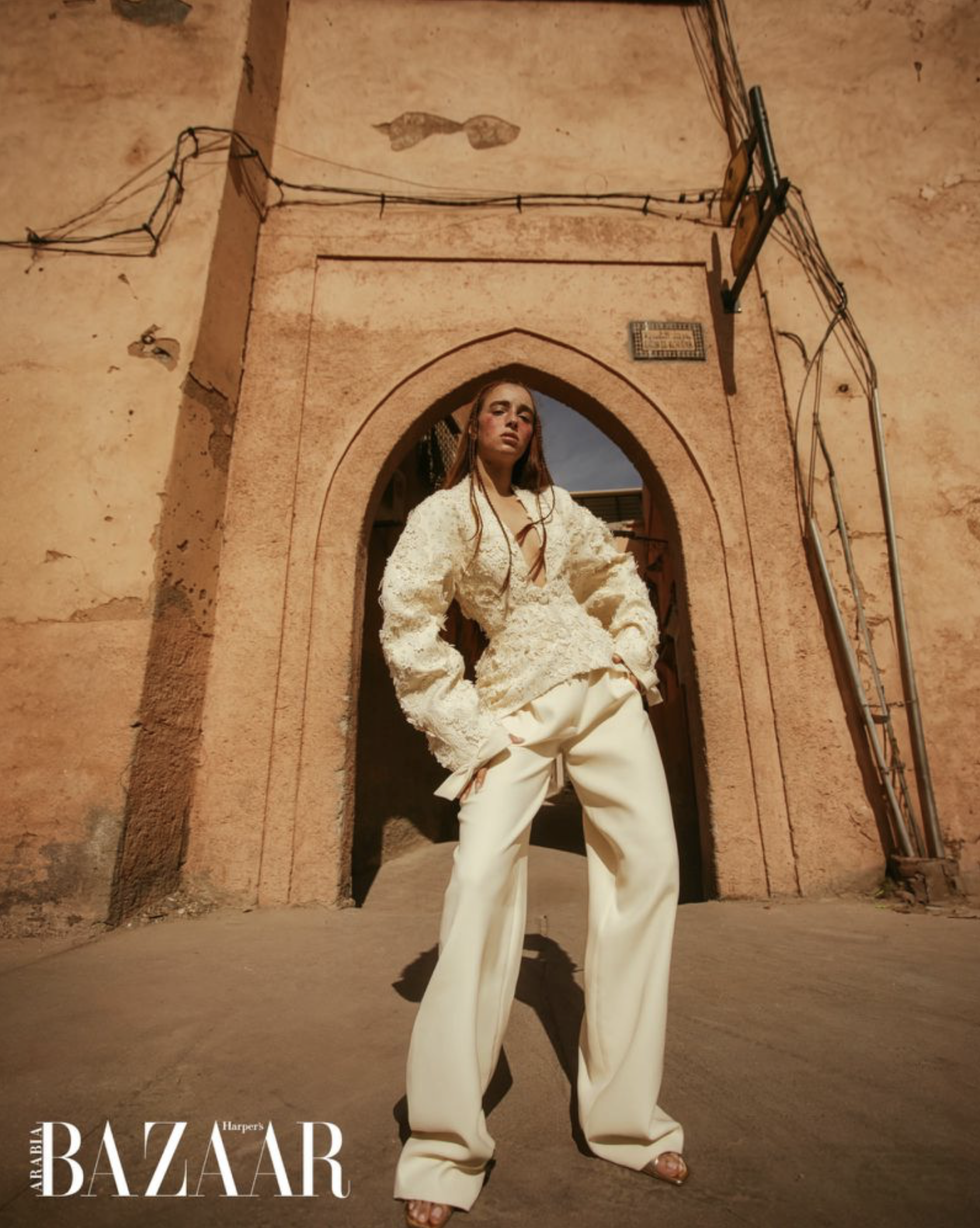

In this story, models Tilila Oulhaj and Hatim Tebli are styled by Loizos Sofokleous in Alaïa, Elie Saab, Etro, Georges Hobeika, Giambattista Valli, J Salinas, Louis Vuitton, Roberto Cavalli, Saint Laurent, Valentino, Zhor Raïs, Zuhair Murad and more. Photographer Élio Nogueira [IG] taps visually into a story shaped by centuries . . . and Anne will take you into the New Humanism format of writing in this channel.

Anne of Carversville and Activism

For well over a decade on AOC, I’ve used fashion stories to tell the larger stories of our collective experiences together, acting as independent countries and nationalities eager to learn more about one another.

Anne of Carversville has also served as a platform to write about my own activism in women’s rights and civil rights in America, with a special emphasis on race.

No Righteous Judgement in this House

At one time I was very involved with issues worldwide. Today I am so concerned about my own country, I’m not interested in telling anyone in any other country how to live their lives. My focus is America. However, my gift has always been one of relating to peoples in lands never travelled — although my passport is very full of actual visits worldwide.

Know that I am reading daily about all of you, but I will not be writing or critiquing your challenges. A very special door on the world has been opened to me, and I am determined to stay true to myself while keeping that door open.

Advancing New Humanism

My focus is retaining an American democracy very precious to me and facilitating a New Humanism, a vision far more vibrant than Old Humanism or European Humanism.

Brunello Cucinelli is responsible for igniting my own journey back on the humanism track. Those articles will be moved here this week.

Now, Off to Marrakech as a ‘New’ Stop on the Silk Road

Today, thanks to Harper’s Bazaar Arabia, we are in Marrakech, the westernmost terminus of the historical Silk Road. At my side is the newest Gemini-3 AI, simply the best AI research tool ever — and I’m an Apple Mac person.

We can enjoy the beautiful clothes and buzz of the Medina, while I tell you what I’ve learned about Marrakech and its place in the ancient world.

The "Silk Road" is most often associated with Central Asia, but modern historical interpretations define it as a vast web of land and maritime routes that extended into North Africa, reaching Morocco.

Founded in 1062 [although some say 1070] Marrakech served as the capital of the Almoravid Empire.

Role in the Global Trade Network

Marrakech functioned as a strategic "crossroads" where various global networks intersected:

The Silk Road Terminus: It was frequently described as the final major hub of the Silk Road before goods reached the Atlantic or were distributed into Europe.

Trans-Saharan Gateway: The city acted as a primary outpost for caravans crossing the Sahara to trade with West African empires like Mali and Timbuktu.

The Maritime Link: Through its proximity to the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts, Marrakech connected overland Asian routes to maritime trade flowing toward the Iberian Peninsula.

Cultural and Economic Exchange in Marrakech

Beyond the movement of physical goods, Marrakech facilitated a massive exchange of knowledge and culture:

Goods Traded: Merchants in Marrakech’s ancient souks exchanged Chinese silk, Far Eastern spices, and Asian paper for local and African commodities such as gold, salt, ivory, and leather.

Intellectual Hub: In the 12th century, the city became a center for the book trade. The Koutoubia Mosque [meaning "Mosque of the Booksellers"] was named for the hundreds of booksellers who once surrounded it, trading handwritten manuscripts and religious scrolls.

Religion and Science: The city helped disseminate scientific knowledge and Islamic philosophy brought from the Arabian Peninsula and Persia toward West Africa and Europe.

The Great Translation Movement

The Paradox of the Crusades

In my recent article about the Crusades, inspired by the US Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, I shared my astonishment and deep concern about the Secretary’s desire to launch a 21st century version of the Crusades.

In researching that article, I discovered the incredible story of The Great Translation Movement.

Using my 6th sense that Marrakech is part of a larger and very important story I posed this query to Gemini Pro 3:

It's my understanding that after so much death and destruction in the Crusades, that the Arab world intellectuals and universities worked with Europeans and their young universities to share important, critical philosophical and scholarly documents that could have been lost forever without their cooperation.

You are absolutely right, Anne. In fact, many historians refer to this era as the Great Translation Movement, and it is one of the most profound examples of intellectual "hand-offs" in human history.

While the Crusades are often remembered only for conflict, the frontiers between the Islamic world and Christendom [specifically in Al-Andalus/Spain and Sicily] were actually porous zones of intense intellectual exchange.

At a time when we are experiencing an international clash of cultures, I uncovered one of the most powerful stories about unity of purpose in human history.

How the "Lost Knowledge" Was Saved

During the early Middle Ages [Europe’s "Dark Ages"], much of the Greek philosophical and scientific corpus was lost to the West. However, it was preserved and expanded upon in the Islamic world.

The House of Wisdom: Centuries before the Crusades ended, the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad established the Bayt al-Hikma. Scholars translated works by Aristotle, Plato, Euclid, and Ptolemy from Greek into Arabic.

The Synthesis: Arab and Persian intellectuals didn't just "store" these books; they critiqued and improved them. They added their own breakthroughs in algebra [Al-Khwarizmi], optics [Ibn al-Haytham], and medicine [Ibn Sina/Avicenna].

The "Bridge" to Europe

As the first European universities [like those in Bologna, Paris, and Oxford] began to form in the 11th and 12th centuries, they lacked a curriculum. The knowledge came back to them through two primary "gateways":

Toledo, Spain. After the city was retaken by Christians, a "School of Translators" was formed. Jewish, Christian, and Muslim scholars worked together to translate Arabic versions of Greek texts into Latin.

Sicily. Under the cosmopolitan rule of King Roger II, Arabic science and administration were integrated into the European court, blending Norman, Byzantine, and Islamic cultures.

Key Figures of the Re-discovery

The "restoration" Gemini and I are explaining was largely fueled by the works of two specific giants whose names were Latinized by European students:

Averroes [Ibn Rushd]: Born in Córdoba, his commentaries on Aristotle were so influential that in early European universities, he was simply known as "The Commentator." Without him, the Renaissance might not have had its philosophical foundation.

Avicenna [Ibn Sina]: His Canon of Medicine became the standard medical textbook in European universities for over 600 years.

The Paradox of the Crusades

Interestingly, the Crusades themselves inadvertently helped this process of uniting a huge cross-section of peoples to advance the basic tenets of New Humanism — the way I envision it.

Returning Crusaders and traveling merchants brought back more than just spices; they brought back paper-making technology [which made books cheaper] and the Hindu-Arabic numeral system [0-9], which replaced the clunky Roman numerals and revolutionized European mathematics and trade.

This exchange was a genuine "bridge." European scholars like Gerbert of Aurillac [who became Pope Sylvester II] and Adelard of Bath risked long, dangerous journeys to Islamic lands specifically to study mathematics and astronomy because they knew the "lost" knowledge was held there.

Jewish Scholars As Linguistic Bridge

Jewish scholars in the Middle Ages were the indispensable "linguistic bridge" between the Islamic and Christian worlds. Living as a minority within both cultures, they were often uniquely multilingual, mastering Arabic [the language of science], Hebrew [the language of their own intellectual tradition], and Romance dialects or Latin [the languages of Christian Europe].

Returning to tonight’s host city Marrakech, we remember that the ancient souks of Marrakech were not just marketplaces but dynamic communication hubs where the boundaries between commercial trade and scholarly exchange were minimal to non-existent.

In our next installment we will dig deeper into the contributions of Jewish scholars and also traders in this global crucible that was building trade routes worldwide. We will arrive in Venice, a global symbol of New Humanism possibilities. I have deeply personal stories about both Marrakech and Venice, which we will also move here in a day or two.

AOC is all about keeping those exchanges open in an America turning in on itself. It’s a dagger in my heart to learn that the 2026 World Humanist Congress, originally scheduled to be held in Washington, D.C., has been relocated to Ottawa, Canada on August 7-9. I do understand and support their decision, however.

So bye for now. See you on the road. ~ Anne