The Middle Ages and America Today | Prompted by Trump DC, We Examine the Crusades

/Columbia University in New York City, October 9, 2023 following the deadly Hamas October 7, 2023 attacks. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license

In 2021, as a US Senator, JD Vance proclaimed “the universities are the enemy” in America. Republicans have waged a war on America’s most prestigious universities for years, without inflicting serious pain. Weeks after Donald J Trump’s second inauguration as US president, the new administration is coming for academia with Elon Musk chainsaw-style.

American universities are not intellectual spaces of innovation, Republicans argue. Rather, they are hotbeds of hate. I’ve had limited access to university campuses in recent years, but there is some evidence to the ‘hotbeds of hate” argument. And while AOC doesn’t support these heavy-handed tactics of the Trump administration, the lack of civility and willingness to debate is a big no-no on both sides of this argument. It takes very little in the form of disagreement to send students — at least the women — to their safe spaces on campuses.

When students at Rutgers demanded that former Secretary of State Condoleezza "Condi" Rice not be allowed to make their 2014 commencement address, Rice herself eventually declined the invite, which promised to result in student protests and sit-ins every day until graduation.

Is America Retreating to the Middle Ages?

It’s shocking to understand that in America, MAGA Republicans want to dial back the rights of women, LGBTQ rights; any and all references to achievements by people of color or women on federal government websites; the defunding of our scientific and medical research institutions . . . The list is stunning.

In trying to sort out what is happening in America and around the world, it’s difficult for liberal-minded people like myself to process just how deeply the MAGA movement detests our current culture. “They want to take us back to the Middle Ages!” I’ve exclaimed to friends and AOC readers both.

My protests come from someone who is not a Marxist or Communist or left-wing radical — no matter what Trump says. My mind is as entrepreneurial as they come — although I have empathy, a quality unknown to Chainsaw Massacre Elon Musk.

I am not weak to accepting new ideas or retesting old ones.

In this moment, my own self-education has taken a strong 180°turn after filtering my assumptions around the Middle Ages through my set of three AI programs. One is dramatically superior in interpreting historical events, and the other two are used as fact checkers against my AI for scholars program.

My first stop was double-checking myself on the facts of the Crusades.

The Mixed Record of the Violent and Bloody Crusades

In recent years, many macho men like US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth have embraced a combative brand of Christianity. Hegseth wrote that people who enjoy the benefits of Western civilization should “thank a Crusader.”

Politico Magazine did a deep dive into Hegseth’s philosophy in this December 6, 2024 article by Jasper Craven: Pete Hegseth’s Crusade to Turn the Military into a Christian Weapon.

On his arm, Hegseth has a tattoo with the words ‘Deus Vult,’ which he has described as a “battle cry” of the Crusades.

“Voting is a weapon, but it’s not enough,” the Defense Secretary wrote in a 2020 book ‘American Crusade’. “We don’t want to fight, but, like our fellow Christians one thousand years ago, we must.”

The historical facts of the Middle Ages do not support this long period of human history as being profound or enlightening. Many would call it gruesome, and it was the most violent period in human history to that date.

And yet, it’s the guiding North Star of many believers in the MAGA movement because religious beliefs around redemption and ‘one God’ — the Christian God . . . their God — lay at its core. Of course, Christians won the Crusades. It was God’s will.

Few MAGA Members Even Know the History of The Crusades

During the eleventh century, Arab governance was split among three main regions: Spain, Egypt, and Iran/Iraq, with the Fatimids of Egypt ruling over Jerusalem. Concurrently, various Islamic leaders commanded their own armies and were engaged in dynastic conflicts and power struggles. By the year 1027, the Byzantine emperor had successfully negotiated improved conditions for Christians living in Jerusalem, leading to the resumption of European pilgrimages to sacred locations. However, the subsequent emergence of the Islamic Seljuk Turks disrupted this period of tranquility, becoming a significant factor that led to the initiation of the First Crusade.

It’s true that the Christians were initially successful in The First Crusade, launched in 1096 and achieving the capture and liberation of Jerusalem. On July 15, 1099, almost two years into their expedition to the Holy Land, the Crusaders managed to capture Jerusalem. Sadly, the papal legate who had traveled with them passed away before this event. His presence had helped to maintain some level of moderation during the journey to Jerusalem, but without him, the crusading forces breached the city walls and carried out widespread killings among its inhabitants. The slaughter of a city’s residents who resisted forces overtaking them was common.

This is not the article for a blow-by-blow history of the Crusades. The Second Crusade resulted in Christian defeats against the growing powers of better-prepared Muslim forces.

The Third Crusade, known for figures like Richard the Lionheart and Saladin, resulted in a compromise, granting Christian pilgrims access to Jerusalem but leaving the city under Muslim control. Further investigation reveals the complex dynamics and shifting allegiances during this era.

The bitter relations throughout the Crusades, culminating in the sack of Constantinople in the Fourth Crusade, put an end to any sense of possible reconciliation between the East and West. It’s plausible to argue that we live with this reality even today.

Despite moments of triumph, the Crusaders ultimately failed to establish a lasting Christian dominion in the Holy Land, underscoring the transient nature of their victories. Does MAGA agree that they lost the Crusades? Hardly.

Fascinated with this history lesson, Anne dug deeper into the intellectual mindset of the Middle Ages — was it as upside down and backwards as I thought. Unafraid to admit when my assumptions were all wrong, let me tell you that Anne was clueless about scholarship in the Middle Ages. I actually blew off an article last year making this exact point that the Middle Ages weren’t as hopelessly backwards as we think.

Universities in the Middle Ages Were Enlightened in Spite of Crusades and Battles for Christian Dominance

European Universities

During the Middle Ages, European universities were vibrant centers of intellectual debate, where theology and philosophy played pivotal roles in shaping academic controversies. These fields provided the framework to explore profound questions concerning existence, ethics, and the divine nature.

The University of Bologna [1088], often regarded as the first university, became renowned for its study of law. Its model attracted scholars and students from across Europe, leading to the spread of similar institutions. Paris followed suit, with The University of Paris [1150] known as the Sorbonne, a university system excelling in theology, philosophy, and the arts. Paris also set standards for curriculum and degree structures.

Further north in England, the University of Oxford [1096] and the University of Cambridge [1209] also emerged as important centers of learning, as did University of Salamanca [1218] in Spain and the University of Padua [1222] in Italy.

Arab World Universities

In the Arab world, Al-Qarawiyyin University, located in Fez, Morocco, was founded in 859 AD by Fatima al-Fihriya, making it the official record holder as the oldest university in the world. AOC cannot validate that claim without researching China. The scholarly activities at Al-Qarawiyyin played a crucial role in preserving and transmitting the accumulated wisdom of ancient civilizations, which would later feed into the European Renaissance.

The University of Al-Mustansiriya, established in 1227 by the Abbasid Caliph Al-Mustansir in Baghdad, stands as a significant landmark in the history of education in the Arab world.

These early Arab institutions fostered a culture of rigorous debate and critical thinking, which encouraged the cross-pollination of ideas between different cultures and civilizations. They were instrumental in translating and preserving ancient Greek and Roman texts, which would later be transmitted to Europe and spur the Renaissance. The methodologies and curricula developed in these universities influenced the establishment of later educational institutions in Europe and the Islamic world.

Just as Jewish and Islamic traders worked well together along the trade routes and in Venice, in particular, it seems that quite a lot of intellectual synergy existed between the Arab universities and scholars and its counterparts in Europe. The saddest examples of a lack of cooperation seem to fall into the category of religious institutions. . . Having this thought, I will run a check against it tomorrow, probing for respect — or lack of it — among university scholars in North Africa and Europe.

Interplay of Faith and Reason at Universities

The intricate interplay between faith and reason was frequently at the heart of medieval scholarly discourse. University scholars engaged vigorously in dialectical exercises, debating the nature of God, the immortality of the soul, and the relationship between divine omniscience and human free will.

These discussions often drew upon the works of classical philosophers like Aristotle, whose ideas were scrutinized alongside Christian doctrine.

The Crusades, emblematic of the era's religious fervor, provided fertile ground for academic debate, illustrating the intersection of theology, politics, and morality. Scholars argued over the ethical justification of these military campaigns. Some defended the Crusades as righteous wars sanctioned by God to reclaim holy lands and protect Christendom, while others criticized them as contrary to Christian teachings on peace and charity.

This controversy reflected broader philosophical questions about the role of violence in achieving moral ends and the responsibilities of Christian rulers and knights. Thus, theology and philosophy not only guided intellectual inquiry but also offered a robust platform for considering the ethical dimensions of contemporary events, such as the Crusades, within the broader tapestry of medieval scholarship.

One of the major controversies centered on the works of Aristotle, which had been preserved and expanded upon by Islamic scholars. This history lesson warrants its own post.

Conflicting interpretations of Aristotle's texts led to debates regarding the nature of the cosmos, motion, and matter. Some argued for a naturalistic explanation of phenomena, seeking to explain events through observable and rational principles. Others maintained that biblical interpretation should guide understanding, emphasizing divine intervention and scriptural authority. This tension was exemplified in discussions about the eternality of the world—whether it had existed forever or had a divine beginning.

Islamic Scholars Had Studied Aristotle Long Before Christians

Bayt al-Hikmah, also known as the House of Wisdom, played a pivotal role during the Abbasid Caliphate, serving as a beacon of intellectual pursuit and scholarly activity in Baghdad. Founded during the reign of Caliph Harun al-Rashid and expanded under his successor, Caliph al-Ma'mun, this institution became a central hub for the translation and preservation of knowledge from diverse cultures and languages.

It symbolized the Abbasids' commitment to learning and innovation, making significant contributions to fields such as mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and philosophy.

The institution attracted scholars from various parts of the world, including Muslims, Christians, Jews, and others, fostering an environment of intellectual diversity and collaboration. Under its auspices, a remarkable translation movement flourished, where Greek, Persian, Indian, and other texts were translated into Arabic, making this knowledge accessible throughout the Islamic world. This period marked an era of enlightenment, where scholars like Al-Khwarizmi and Al-Razi made groundbreaking contributions that would later influence the European Renaissance.

Bayt al-Hikmah was not merely a library but a vibrant center for research, discussion, and experimentation. It epitomized the Abbasid Caliphate's emphasis on intellectual exploration and cultural integration, laying foundations for scientific and philosophical advancements. The legacy of Bayt al-Hikmah underscored the transformative power of knowledge, demonstrating how cultural and intellectual exchange can drive progress across civilizations.

Islamic scholars had engaged with Aristotelian texts much earlier, through translations and commentaries that were heavily influenced by the intellectual dynamism of the Islamic Golden Age. Figures such as Avicenna and Averroes offered interpretations that were deeply embedded in Islamic philosophical traditions. Unlike their Christian counterparts, Islamic philosophers frequently explored Aristotle's natural philosophy and metaphysics on their own terms, occasionally challenging orthodoxies but generally incorporating Aristotelian ideas into a broader Islamic intellectual framework that emphasized reason as a means to understanding divine truths.

Scientific inquiry at European universities was spurred by figures such as Roger Bacon and later, Thomas Aquinas, who aimed to integrate reason with faith. They acknowledged the potential of empirical observation while maintaining theological boundaries. These intellectual battles laid foundational stones for future scientific explorations, showcasing the complex interplay between faith, reason, and the growing awareness of natural law during the medieval period.

Defining Natural Law

Natural law is a philosophical concept that suggests there is a set of moral and ethical principles inherent in human nature, which can be discerned through human reason. These principles are thought to be universal and unchanging, providing a foundation for human conduct that transcends individual cultures and societal norms. The idea is predicated on the belief that there exists a natural order to the universe, governed by reason and logic, which can guide human actions towards what is inherently right and just.

This last paragraph is profound, especially in the context of today’s university debates — which are not debates at all. Nor are meetings in Congress the source of intellectual debate.

I am eager to get to the Renaissance, but we cannot skim over the Black Plague or Black Death which preceded this exciting time for humanity — and also one that created themes that are repugnant to most of us today. AOC tries hard to never omit the totality of what was going on in the world at any given time.

As theories of dismissing vaccinations and a disregard for the possibility of another plague dominate the Trump Administration, it’s important to understand the Black Plague or Black Death because it decimated an estimated one-third of Europe’s population.

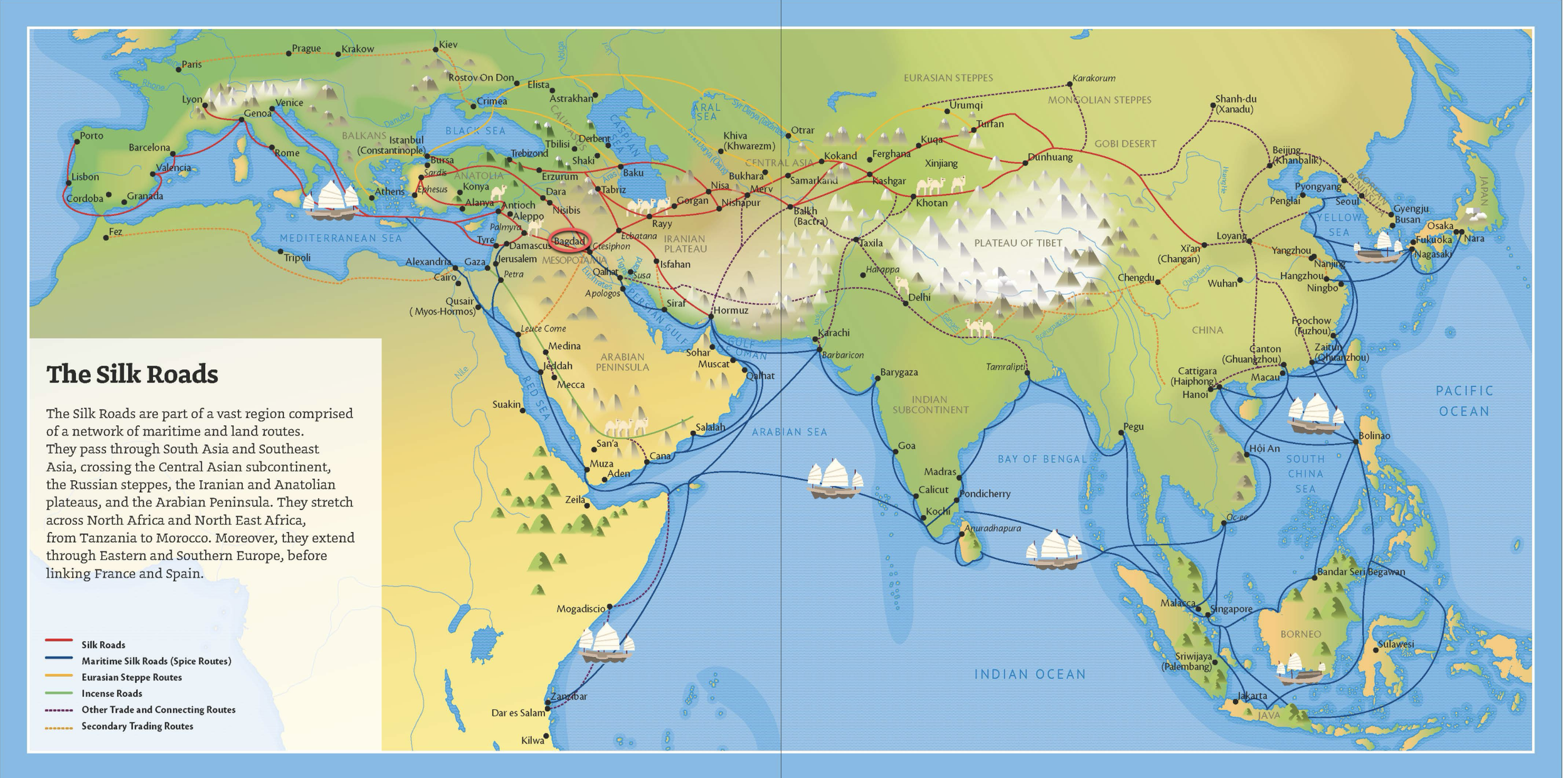

Following the path of the famous Silk Road Routes, we will outline exactly who was impacted and who not so much by the plague.

As an aside, one of the most interesting facts AOC discovered a couple years back was the trade routes that existed pre-colonization of Africa between India and East Africa. You can see the routes in this map.

I don’t speak of this alleged fact often, because I only have a single source of the ‘scientific’ discovery that women merchants were on those boats moving between India and East Africa. Presumably, they were traveling with their husbands or family members. But it’s a radical thought, if true.

Now that AOC uses this scholars AI program, it’s much easier for me to pursue the facts of the original report on Science Daily. ~ Anne