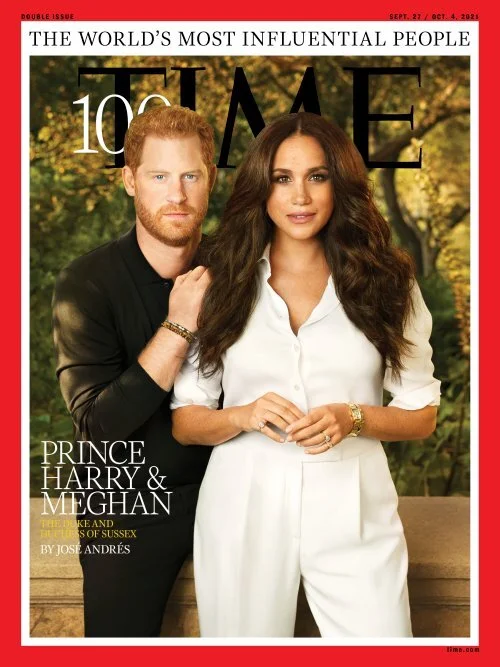

TIME 100 Icons Meghan and Harry Call Global Citizens to Action in Central Park

/Harry and Meghan head the list: TIME 100 Most Influential People

Prince Harry and Meghan, The Duke and Duchess of Sussex, are headliners in this year’s TIME 100. Their own narrative was written by Spanish chef José Andrés, founder of World Central Kitchen, a non-profit devoted to providing meals in the wake of natural disasters.

The trio combined their activist energies in December 2020, when José Andrés and his non-profit, World Central Kitchen, became the first major charitable contribution of Harry and Meghan’s Archwell charity.

Harry and Meghan | Dr. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweaka | UN Ambassador Linda Thomas Greenfield

AOC wrote about Harry and Meghan’s activist work on COVID vaccinations worldwide in our introduction of TIME 100: Dr. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, Director General of the World Trade Organization. Prince Harry and Meghan asked the question: what will it take to vaccinate the world? “Unity, cooperation and Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala,” is their answer.

As Chair of the Board of Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (2016 – 2020) and also AU COVID-19 Special Envoy and WHO COVID-19 Special Envoy, Okonjo-Iweala has existing skills and knowledge around global vaccine efforts.

Writing about the Trump administration’s blocking of Okonjo-Iweala’s rise to head of the WTO, we noted her close relationship with Linda Thomas-Greenfield, now US President Biden’s UN Ambassador. As we predicted, one of the very first initiatives in the new Biden Administration was to end the Trump blockade against Dr. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala.

Global Citizens Held Hands September 24th in Central Park

AOC’s dot-connecting came full circle on Saturday with the truly epic Global Citizen concert that ran for 24 hrs. moving around the globe. The New York City Central Park action went live post-Paris at about 5pm. An hour or two in to the concert, it was clear that someone was in the house. Cries of glee, clapping — some rock star had arrived.

Well, they are rock stars — Meghan and Harry — and it was our chance to claim them as our own. The crowd was in love with the couple — as is AOC. Are they perfect? No, for heavens sake. And who is? We are so happy to have these global activists making their home now in America. We need them here, as America tries to get our act together once again.

“My wife and I believe that where you’re born should not dictate your ability to survive,” Prince Harry said. “So Global Citizens, we ask you tonight: Do you think we should start treating access to the vaccine as a basic human right?

“When we start making decisions through that lens, where every single person deserves equal access to the vaccine, then we can achieve what is needed together for all of us,” he added.

And then who did Harry and Meghan introduce next at the Global Citizen ? UN ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield, who they met for the first time earlier in their New York City visit.

Harry and Meghan: Glamping in Botswana to Hollywood Royalty

The Wall Street Journal wrote last week Prince Harry and Meghan Hustle to Become Royalty — in Hollywood. Like the Obamas, the couple has media deals with Netflix and Spotify and have already produced a six-segment mental health series for Apple TV.

29 Million US viewers watched Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s 2018 wedding, compared to 23 million US viewers for Prince William and Kate Middleton. Our own postings about Harry and Meghan’s wedding remain high in Google search results.

In fact, it wasn’t the wedding that was on my mind last week, when thinking about Harry and Meghan pre-Global Citizens Concert. I’ve always been interested in the trend towards glamping. My partner’s children thought it was hilarious that I once wore kitten heels on a camping trip and took about 100 pics of my feet.

It was then that I knew glamping, not camping, was in my future. Writing about an imaginary wedding proposal on a glamping trip — inspired by a real life wedding featured in British Vogue — triggered my memory of writing about Harry and Meghan’s third date — when they flew to Botswana in Africa.

As Harry put it: “We camped out with each other under the stars, sharing a tent and all that stuff. It was fantastic.”

In the AOC article Harry was promoting the National Geographic documentary ‘‘Into the Okavango’ . I couldn’t help thinking about Harry and Meghan and Harry’s profound attachment to Africa. Harry described his pre-Meghan relationship to Africa as one in which he loses himself in the bush. “This is where I feel more like myself than anywhere else in the world. I wish I could spend more time here….”

Writing about energy vortexes on AOC’s imaginary glamping trip to the American Southwest, I knew that Harry and Meghan would share the same enthusiasm, based on their third date at Botswana’s sustainable Meno a Kwena safari lodge.

Botswana’s sustainable Meno a Kwena safari lodge. Courtesy