Explaining Critical Race Theory: What It Is and What It Is Not

/By David Miguel Gray, Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Affiliate, Institute for Intelligent Systems, University of Memphis. First published on The Conversation

U.S. Rep. Jim Banks of Indiana sent a letter to fellow Republicans on June 24, 2021, stating: “As Republicans, we reject the racial essentialism that critical race theory teaches … that our institutions are racist and need to be destroyed from the ground up.”

Kimberlé Crenshaw, a law professor and central figure in the development of critical race theory, said in a recent interview that critical race theory “just says, let’s pay attention to what has happened in this country, and how what has happened in this country is continuing to create differential outcomes. … Critical Race Theory … is more patriotic than those who are opposed to it because … we believe in the promises of equality. And we know we can’t get there if we can’t confront and talk honestly about inequality.”

Rep. Banks’ account is demonstrably false and typical of many people publicly declaring their opposition to critical race theory. Crenshaw’s characterization, while true, does not detail its main features. So what is critical race theory and what brought it into existence?

The development of critical race theory by legal scholars such as Derrick Bell and Crenshaw was largely a response to the slow legal progress and setbacks faced by African Americans from the end of the Civil War, in 1865, through the end of the civil rights era, in 1968. To understand critical race theory, you need to first understand the history of African American rights in the U.S.

The History

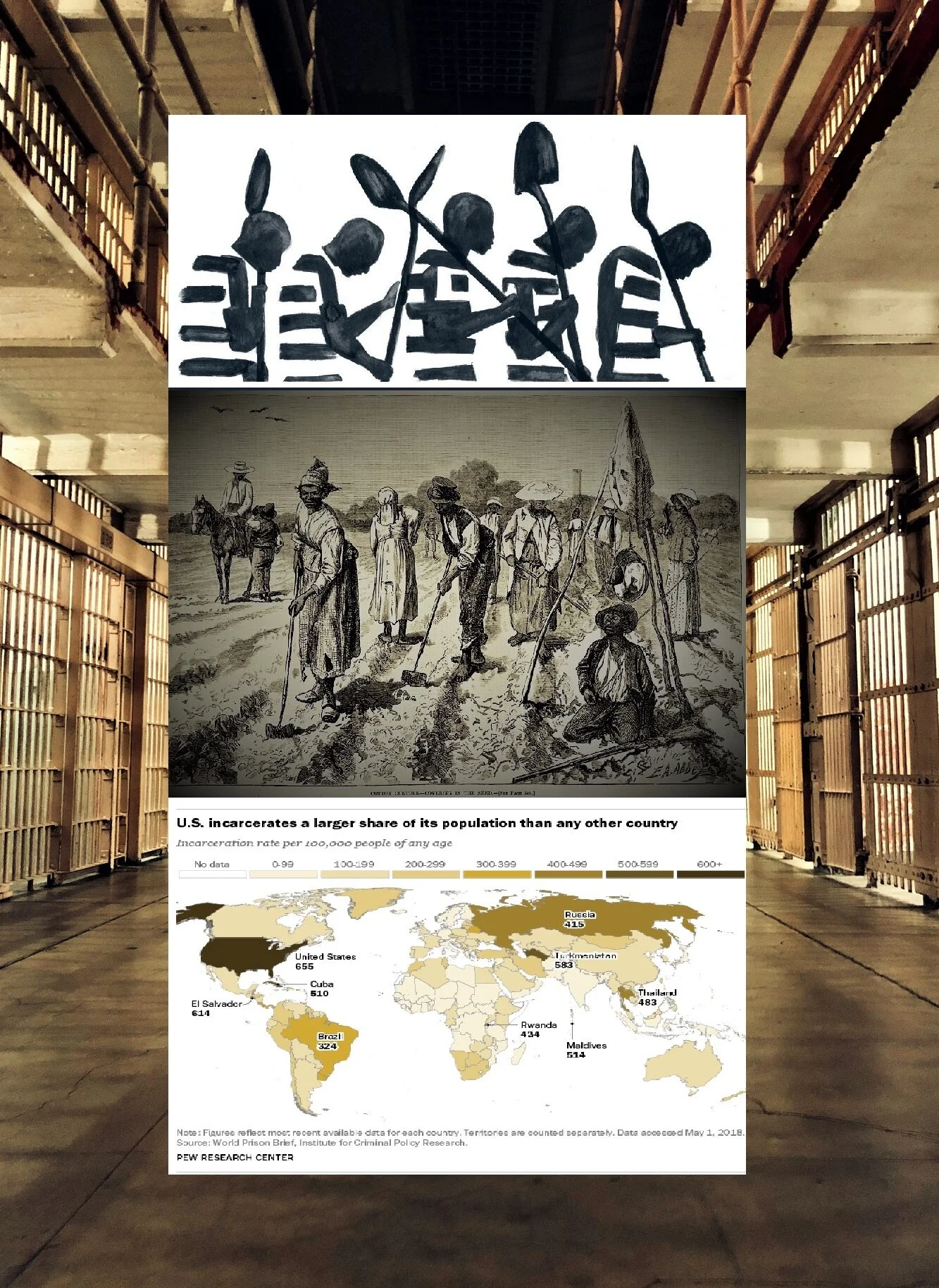

After 304 years of enslavement, then-former slaves gained equal protection under the law with passage of the 14th Amendment in 1868. The 15th Amendment, in 1870, guaranteed voting rights for men regardless of race or “previous condition of servitude.”

Between 1866 and 1877 – the period historians call “Radical Reconstruction” – African Americans began businesses, became involved in local governance and law enforcement and were elected to Congress.

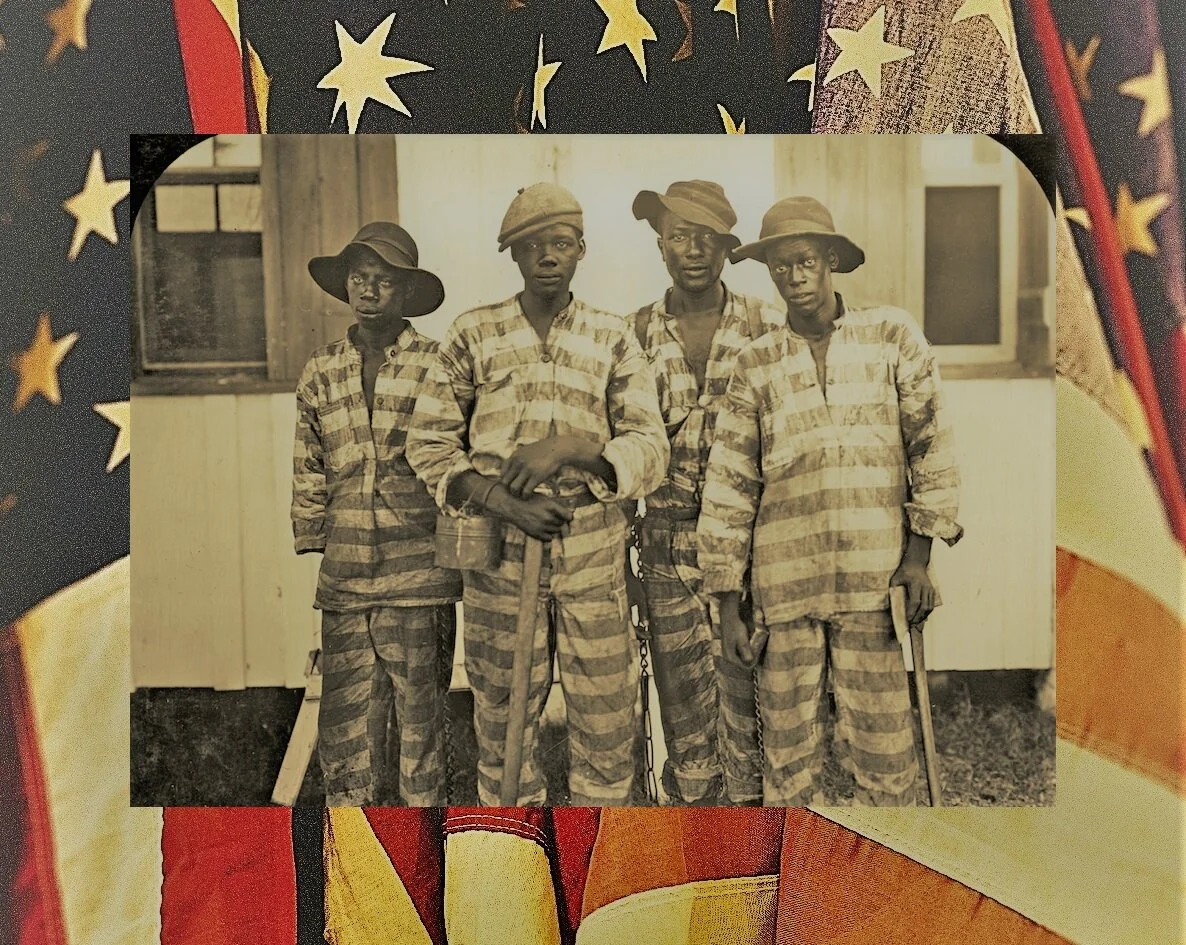

This early progress was subsequently diminished by state laws throughout the American South called “Black Codes,” which limited voting rights, property rights and compensation for work; made it illegal to be unemployed or not have documented proof of employment; and could subject prisoners to work without pay on behalf of the state. These legal rollbacks were worsened by the spread of “Jim Crow” laws throughout the country requiring segregation in almost all aspects of life.

Grassroots struggles for civil rights were constant in post-Civil War America. Some historians even refer to the period from the New Deal Era, which began in 1933, to the present as “The Long Civil Rights Movement.”

The period stretching from Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, which found school segregation to be unconstitutional, to the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which prohibited discrimination in housing, was especially productive.

The civil rights movement used practices such as civil disobedience, nonviolent protest, grassroots organizing and legal challenges to advance civil rights. The U.S.’s need to improve its image abroad during the Cold War importantly aided these advancements. The movement succeeded in banning explicit legal discrimination and segregation, promoted equal access to work and housing and extended federal protection of voting rights.

However, the movement that produced legal advances had no effect on the increasing racial wealth gap between Blacks and whites, while school and housing segregation persisted.

What critical race theory is

Critical race theory is a field of intellectual inquiry that demonstrates the legal codification of racism in America.

Through the study of law and U.S. history, it attempts to reveal how racial oppression shaped the legal fabric of the U.S. Critical race theory is traditionally less concerned with how racism manifests itself in interactions with individuals and more concerned with how racism has been, and is, codified into the law.

There are a few beliefs commonly held by most critical race theorists.

First, race is not fundamentally or essentially a matter of biology, but rather a social construct. While physical features and geographic origin play a part in making up what we think of as race, societies will often make up the rest of what we think of as race. For instance, 19th- and early-20th-century scientists and politicians frequently described people of color as intellectually or morally inferior, and used those false descriptions to justify oppression and discrimination.

Second, these racial views have been codified into the nation’s foundational documents and legal system. For evidence of that, look no further than the “Three-Fifths Compromise” in the Constitution, whereby slaves, denied the right to vote, were nonetheless treated as part of the population for increasing congressional representation of slave-holding states.

Third, given the pervasiveness of racism in our legal system and institutions, racism is not aberrant, but a normal part of life.

Fourth, multiple elements, such as race and gender, can lead to kinds of compounded discrimination that lack the civil rights protections given to individual, protected categories. For example, Crenshaw has forcibly argued that there is a lack of legal protection for Black women as a category. The courts have treated Black women as Black, or women, but not both in discrimination cases – despite the fact that they may have experienced discrimination because they were both.

These beliefs are shared by scholars in a variety of fields who explore the role of racism in areas such as education, health care and history.

Finally, critical race theorists are interested not just in studying the law and systems of racism, but in changing them for the better.

What critical race theory is not

“Critical race theory” has become a catch-all phrase among legislators attempting to ban a wide array of teaching practices concerning race. State legislators in Arizona, Arkansas, Idaho, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas and West Virginia have introduced legislation banning what they believe to be critical race theory from schools.

But what is being banned in education, and what many media outlets and legislators are calling “critical race theory,” is far from it. Here are sections from identical legislation in Oklahoma and Tennessee that propose to ban the teaching of these concepts. As a philosopher of race and racism, I can safely say that critical race theory does not assert the following:

(1) One race or sex is inherently superior to another race or sex;

(2) An individual, by virtue of the individual’s race or sex, is inherently privileged, racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or subconsciously;

(3) An individual should be discriminated against or receive adverse treatment because of the individual’s race or sex;

(4) An individual’s moral character is determined by the individual’s race or sex;

(5) An individual, by virtue of the individual’s race or sex, bears responsibility for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race or sex;

(6) An individual should feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or another form of psychological distress solely because of the individual’s race or sex.

What most of these bills go on to do is limit the presentation of educational materials that suggest that Americans do not live in a meritocracy, that foundational elements of U.S. laws are racist, and that racism is a perpetual struggle from which America has not escaped.

Americans are used to viewing their history through a triumphalist lens, where we overcome hardships, defeat our British oppressors and create a country where all are free with equal access to opportunities.

Obviously, not all of that is true.

Critical race theory provides techniques to analyze U.S. history and legal institutions by acknowledging that racial problems do not go away when we leave them unaddressed.