5 Ways MacKenzie Scott's $5.8B Commitment to Social and Economic Justice Is a Model for Other Donors (Copy)

/By Elizabeth J. Dale, Assistant Professor of Nonprofit Leadership, Seattle University. Forst published on The Conversation.

The author and philanthropist MacKenzie Scott announced on Dec. 15 that she had given almost US$4.2 billion to hundreds of nonprofits. It was her second announcement of this kind since she first publicly discussed her giving intentions in May of 2019.

In July 2020, Scott revealed that she’d already given away nearly $1.7 billion to 116 organizations, many of which focused on racial justice, women’s rights, LGBTQ equality, democracy and climate change. All told, her 2020 philanthropy totals more than $5.8 billion. Scott directed her latest round of giving to 384 organizations to support people disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. She made dozens of gifts to food banks, United Way chapters, YMCAs and YWCAs – organizations that have seen increased demand for services and, in some cases, declines in philanthropic gifts.

In the two blog posts she has written to break the news, Scott has encouraged donors of all means to join her, whether those gifts are money or time.

Previously married to Amazon founder and CEO Jeff Bezos, the philanthropist announced in July that from now on she’ll be using her middle name as her new last name. She left it up to the causes she’s funding to reveal precise totals for each gift.

Morgan State University and Virginia State University, two of several historically Black colleges and universities receiving her donations, said these were the biggest gifts they’d ever gotten from an individual donor. A number of her gifts are also funding tribal colleges as well as community colleges.

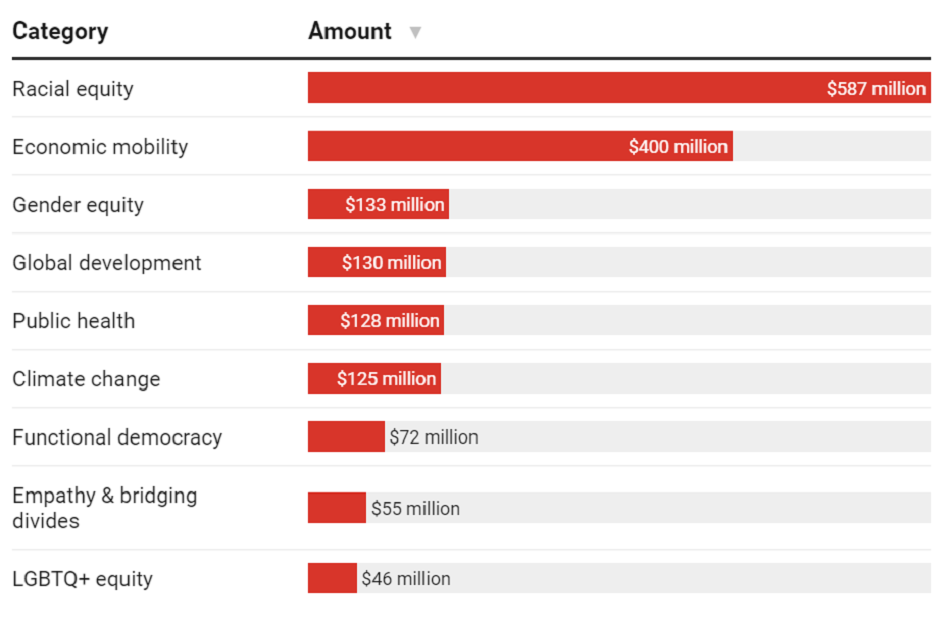

MacKenzie Scott's Philanthropy Priorities

MacKenzie Scott announced in 2019 that she would give away at least half of her fortune, which is worth tens of billions of dollars. In July 2020, she disclosed an initial round of gifts totaling nearly $1.7 billion.

As a scholar of philanthropy, I believe that Scott is modeling five best practices for social change giving.

Amounts shown do not reflect the $4.2 billion in additional giving Scott announced in December 2020.

Table: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND Source: MacKenzie Scott

1. Don’t attach strings

All of Scott’s gifts – many in the millions or tens of millions, like the $30 million she gave Hampton University and the $40 million to the Local Initiatives Support Corporation, which advocates for and builds affordable housing – were made without restrictions. Rather than specify a purpose, as many large donors do, Scott made it clear that she trusts the organizations’ leaders by providing absolute flexibility in terms of how to use her money to pursue their missions. This hands-off approach gives nonprofits an unusual amount of freedom to innovate while equipping them to weather crises like the coronavirus pandemic without stringent restrictions imposed by donors.

2. Champion representation

According to Scott, 91% of the racial equity organizations she funded in her initial round of massive giving, such as the Movement for Black Lives and LatinoJustice, are run by leaders of color. All of the LGBTQ equity organizations, such as the National Center for Lesbian Rights and the Transgender Law Center, that she’s backing are led by LGBTQ leaders. And 83% of the gender equity organizations, such as the Indian nonprofit Educate Girls, are run by women. She says this approach brings “lived experience to solutions for imbalanced social systems.” Backing groups led by people directly affected by an issue is a common tenet of social justice giving at a time when organizations led by people of color receive less funding than white-led groups.

In addition, some of her other gifts to grassroots organizations like Southerners on New Ground, an LGBTQ community-organizing nonprofit, and Southern Partners Fund direct support to a region of the U.S. that is often overlooked by donors and foundations.

3. Act first, talk later

Rather than making lengthy announcements about her plans, Scott chose to distribute this money rapidly and directly. Unlike philanthropic peers like Priscilla Chan and Mark Zuckerberg, or Bill and Melinda Gates, Scott’s first round of giving wasn’t channeled through a large-scale foundation or other entity, like the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, bearing her own name or that of another billionaire. And when she made her public announcement, the gifts were already made.

4. Don’t obsess about scale

Many of the organizations receiving these gifts are relatively small in scale and lack widespread name recognition. The multiracial justice group Forward Together and the Campaign for Female Education, a global aid group often called CAMFED, for example, until recently operated on annual budgets of $5.5 million or less, while the Millennial Action Project had an even smaller budget.

5. Leverage more than money

Philanthropy that’s intended to bring about social change inherently expresses the donor’s values, Scott acknowledged in her announcement. She also recognized her immense privilege, highlighting the need to address societal structures that sustain inequality. And like the many women donors I’ve interviewed and studied, she is using her position as the world’s second-wealthiest woman to amplify the voices of the leaders and groups she supported. Her goal is to encourage others to give, join or volunteer to support those same causes.

As Scott noted, the issues her philanthropy addresses are complex and will require sustained and broad-based efforts to solve.

This is an updated version of an article published on July 30, 2020.