Louisiana Votes to Keep Slavery | Exploiting Black Labor after the Abolition of Slavery

/Update: On Election Day, Tuesday November 8, 2022, Louisiana voters chose to keep language in the state constitution that permits slavery and involuntary servitude as punishment for crime.

Four other states Alabama, Oregon, Tennessee and Vermont voted to adjust the language in their state constitutions that could curtail the use of prison labor.

The 13th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified by Congress on Dec. 6, 1865, states:

“Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

_____ Previously _____

AOC shares our earlier article dedicated to the rise of prison labor after slaves were freed across America.

Published December 5, 2020

By Kathy Roberts Forde, Chair, Associate Professor, Journalism Department, University of Massachusetts Amherst; Bryan Bowman, Undergraduate journalism major, University of Massachusetts Amherst. First published on The Conversation.

The U.S. criminal justice system is driven by racial disparity.

The Obama administration pursued a plan to reform it. An entire news organization, The Marshall Project, was launched in late 2014 to cover it. Organizations like Black Lives Matter and The Sentencing Project are dedicated to unmaking a system that unjustly targets people of color.

But how did we get this system in the first place? Our ongoing historical research project investigates the relationship between the press and convict labor. While that story is still unfolding, we have learned what few Americans, especially white Americans, know: the dark history that produced our current criminal justice system.

If anything is to change – if we are ever to “end this racial nightmare, and achieve our country,” as James Baldwin put it – we must confront this system and the blighted history that created it.

During Reconstruction, the 12 years following the end of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, former slaves made meaningful political, social and economic gains. Black men voted and even held public office across the South. Biracial experiments in governance flowered. Black literacy surged, surpassing those of whites in some cities. Black schools, churches and social institutions thrived.

As the prominent historian Eric Foner writes in his masterwork on Reconstruction, “Black participation in Southern public life after 1867 was the most radical development of the Reconstruction years, a massive experiment in interracial democracy without precedent in the history of this or any other country that abolished slavery in the nineteenth century.”

But this moment was short-lived.

As W.E.B. Du Bois wrote, the “slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery.”

History is made by human actors and the choices they make.

According to Douglas Blackmon, author of “Slavery by Another Name,” the choices made by Southern white supremacists after abolition, and the rest of the country’s accommodation, “explain more about the current state of American life, black and white, than the antebellum slavery that preceded.”

Designed to reverse black advances, Redemption was an organized effort by white merchants, planters, businessmen and politicians that followed Reconstruction. “Redeemers” employed vicious racial violence and state legislation as tools to prevent black citizenship and equality promised under the 14th and 15th amendments.

By the early 1900s, nearly every southern state had barred black citizens not only from voting but also from serving in public office, on juries and in the administration of the justice system.

The South’s new racial caste system was not merely political and social. It was thoroughly economic. Slavery had made the South’s agriculture-based economy the most powerful force in the global cotton market, but the Civil War devastated this economy.

How to build a new one?

Ironically, white leaders found a solution in the 13th Amendment, which ended slavery in the United States in 1865. By exploiting the provision allowing “slavery” and “involuntary servitude” to continue as “a punishment for crime,” they took advantage of a penal system predating the Civil War and used even during Reconstruction.

A new form of control

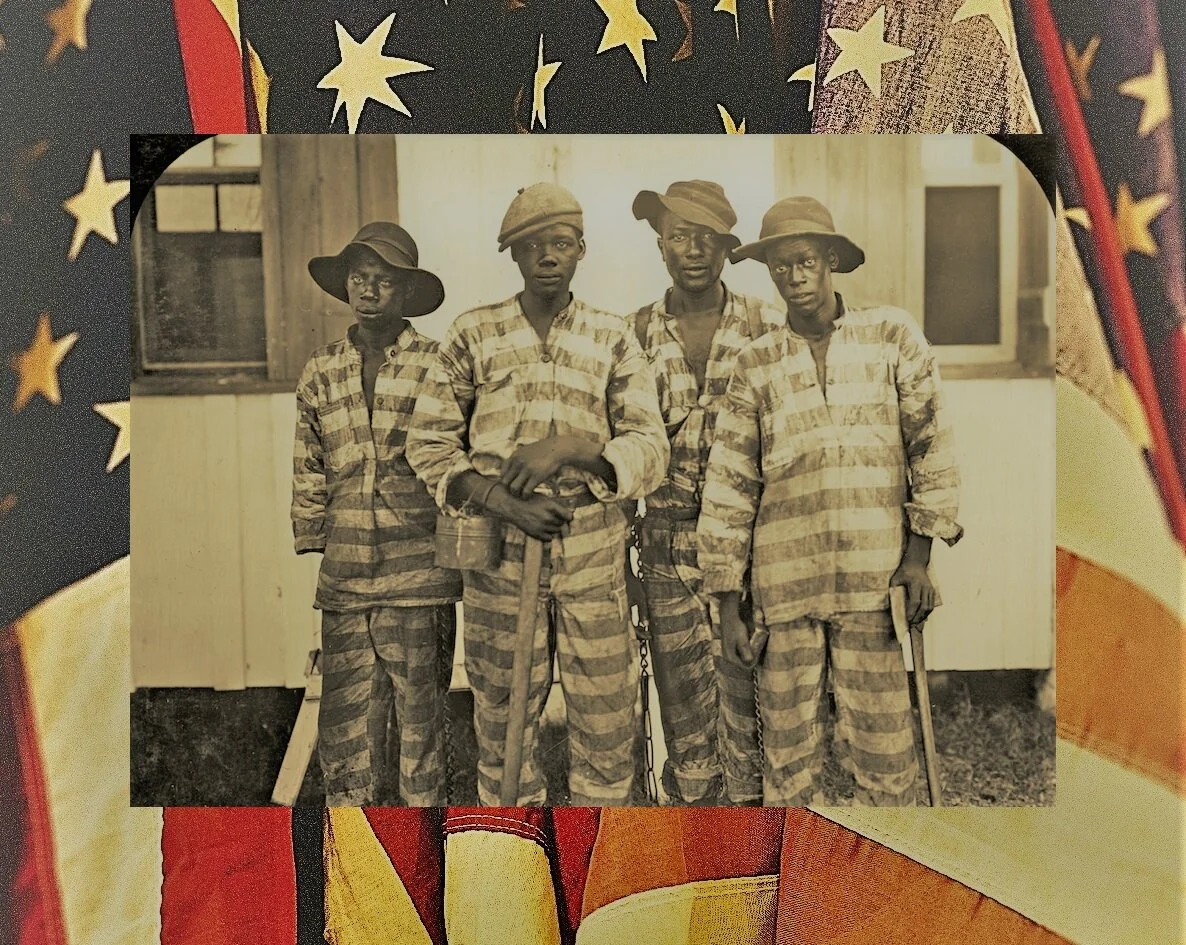

With the help of profiteering industrialists they found yet a new way to build wealth on the bound labor of black Americans: the convict lease system.

Here’s how it worked. Black men – and sometimes women and children – were arrested and convicted for crimes enumerated in the Black Codes, state laws criminalizing petty offenses and aimed at keeping freed people tied to their former owners’ plantations and farms. The most sinister crime was vagrancy – the “crime” of being unemployed – which brought a large fine that few blacks could afford to pay.

Black convicts were leased to private companies, typically industries profiteering from the region’s untapped natural resources. As many as 200,000 black Americans were forced into back-breaking labor in coal mines, turpentine factories and lumber camps. They lived in squalid conditions, chained, starved, beaten, flogged and sexually violated. They died by the thousands from injury, disease and torture.

For both the state and private corporations, the opportunities for profit were enormous. For the state, convict lease generated revenue and provided a powerful tool to subjugate African-Americans and intimidate them into behaving in accordance with the new social order. It also greatly reduced state expenses in housing and caring for convicts. For the corporations, convict lease provided droves of cheap, disposable laborers who could be worked to the extremes of human cruelty.

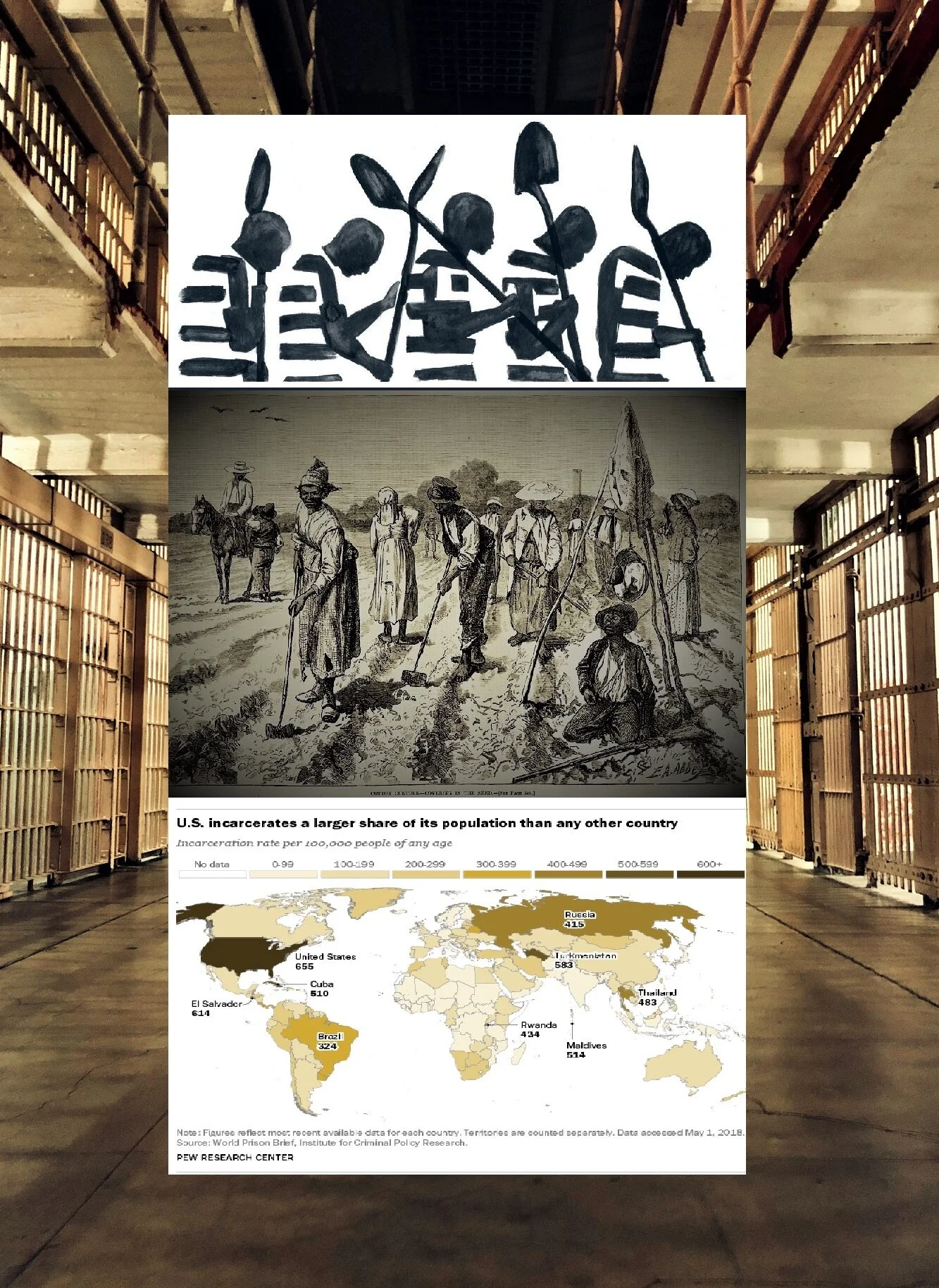

Every southern state leased convicts, and at least nine-tenths of all leased convicts were black. In reports of the period, the terms “convicts” and “negroes” are used interchangeably.

Of those black Americans caught in the convict lease system, a few were men like Henry Nisbet, who murdered nine other black men in Georgia. But the vast majority were like Green Cottenham, the central figure in Blackmon’s book, who was snatched into the system after being charged with vagrancy.

A principal difference between antebellum slavery and convict leasing was that, in the latter, the laborers were only the temporary property of their “masters.” On one hand, this meant that after their fines had been paid off, they would potentially be let free. On the other, it meant the companies leasing convicts often absolved themselves of concerns about workers’ longevity. Such convicts were viewed as disposable and frequently worked beyond human endurance.

The living conditions of leased convicts are documented in dozens of detailed, firsthand reports spanning decades and covering many states. In 1883, Blackmon writes, Alabama prison inspector Reginald Dawson described leased convicts in one mine being held on trivial charges, in “desperate,” “miserable” conditions, poorly fed, clothed, and “unnecessarily chained and shackled.” He described the “appalling number of deaths” and “appalling numbers of maimed and disabled men” held by various forced-labor entrepreneurs spanning the entire state.

Dawson’s reports had no perceptible impact on Alabama’s convict leasing system.

The exploitation of black convict labor by the penal system and industrialists was central to southern politics and economics of the era. It was a carefully crafted answer to black progress during Reconstruction – highly visible and widely known. The system benefited the national economy, too. The federal government passed up one opportunity after another to intervene.

Convict lease ended at different times across the early 20th century, only to be replaced in many states by another racialized and brutal method of convict labor: the chain gang.

Convict labor, debt peonage, lynching – and the white supremacist ideologies of Jim Crow that supported them all – produced a bleak social landscape across the South for African-Americans.

Black Americans developed multiple resistance strategies and gained major victories through the civil rights movement, including Brown v. Board of Education, the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act. Jim Crow fell, and America moved closer than ever to fulfilling its democratic promise of equality and opportunity for all.

But in the decades that followed, a “tough on crime” politics with racist undertones produced, among other things, harsh drug and mandatory minimum sentencing laws that were applied in racially disparate ways. The mass incarceration system exploded, with the rate of imprisonment quadrupling between the 1970s and today.

Michelle Alexander famously calls it “The New Jim Crow” in her book of the same name.

Today, the U.S. has the highest incarceration rate of any country in the world, with 2.2 million behind bars, even though crime has decreased significantly since the early 1990s. And while black Americans make up only 13 percent of the U.S. population, they make up 37 percent of the incarcerated population. Forty percent of police killings of unarmed people are black men, who make up merely 6 percent of the population, according to a 2015 Washington Post report.

It doesn’t have to be this way. We can choose otherwise.