2017 Whitney Biennial Curators Lew & Lockshave Stand Firm On 'Open Casket' Controversy

/2017 Whitney Biennial Co-Curator Responds To 'Open Casket' Controversy

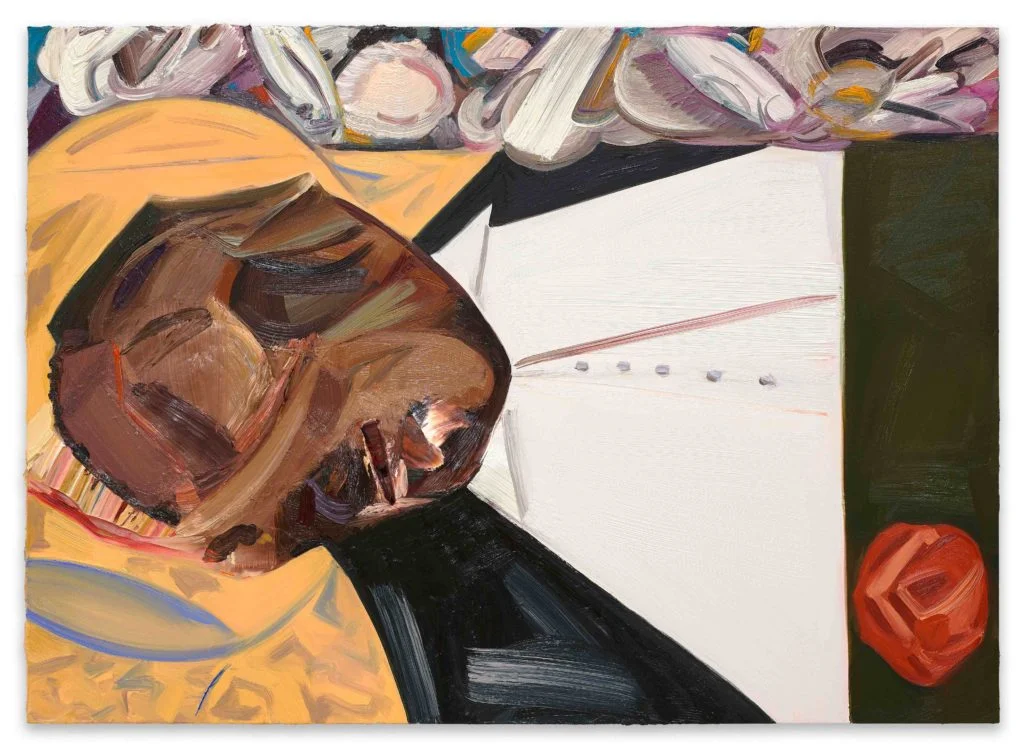

Not in recent memory has a single painting caused such controversy and furor in the contemporary art world as Dana Schutz's 'Open Casket' (2016), part of New York's current Whitney Biennial. The portrait focuses on the disfigured corpse of Emmett Till, murdered in 1955 at age 14 by a Mississippi lynch mob after conflicting stories about whistling -- or 'worse' according to suggestive innuendos in court testimony -- at a white woman.

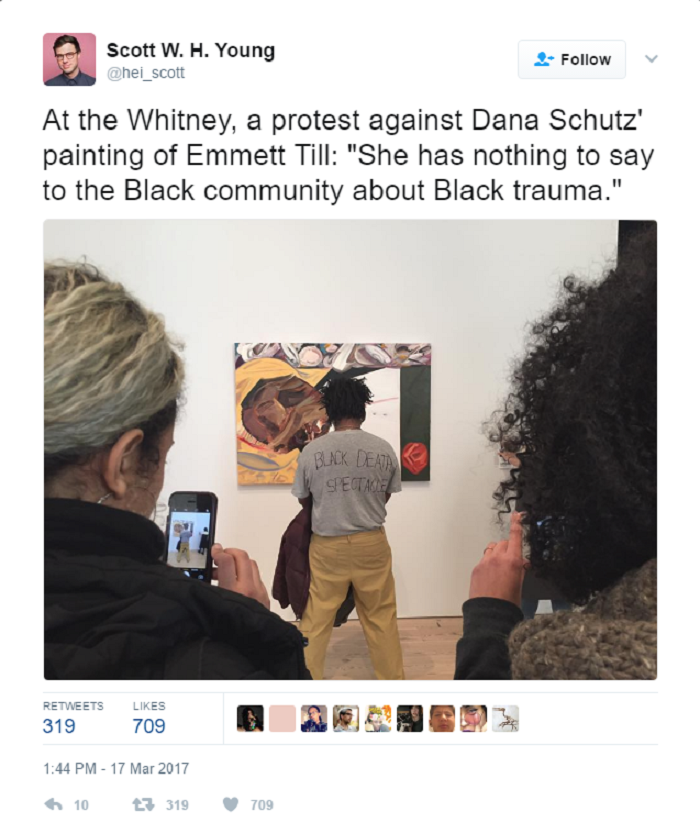

AOC previously covered the protests around Schutz and her painting; her right to paint it in the first place as a white woman; artist Parker Bright's standing guard over the painting wearing a t-shirt and a scrawled message 'Black Death Spectacle'; the demands of British artist Hannah Black that 'Open Casket' be stripped from the show and destroyed; and a false apology letter and request for removal by Schutz that was widely circulated with no verification of the author's identity.

The two Biennial creators Christopher Lew and Mia Lockshave also become the target of criticism, and Artnet New's editor-in-chief Andrew Goldstein spoke to Lew about the controversy.

It's easy to forget that there are 62 other artists in the Whitney Biennial with all the controversy around 'Open Casket'. Referencing the dynamic playing out in the summer of 2016, when final curatorial decisions were being made for the Biennial, Goldstein summarizes America's mindset:

I think it’s useful to remember back to this time, in the summer of 2016, because the furious churn of the news cycle has propelled the national psyche to a different place since then. The country was in a state of extreme trauma. Terrorist attacks in Europe and at home had everyone on edge, police were brutally killing black men in the streets, protests were blazing across America, and specters of the gruesome 20th century were reappearing in headlines in the form of Nazi rallies, white supremacists, and the Ku Klux Klan. Add to this the yawning economic polarization between the classes and it truly felt like society was falling apart—a climate that Donald Trump exploited with his call to a ferocious, nativist populism. Your show seems to specifically address this horrific moment, for instance with another Dana Schutz painting that greets visitors as they reach the fifth floor: a painting of people crammed in an elevator, literally tearing each other limb from limb, evidently out of rage born by pure proximity. Why did you commission that painting specially for the show?

It speaks to the heatedness in the US and the world at large over the last year or two—those issues you point out that are not new to the country but have become recently more visible. Dana had already been working on a series of elevator paintings, so we weren’t asking her to create something completely new, only to think of an elevator painting in the context of the Whitney—to think about the size of our art elevator and to use that as a launching point.

Reality is that most of the people - including AOC -- are talking about the Emmett Till painting without having seen it. We are looking at 'Open Casket' and talking about it based on Internet images -- and not within its context of a large number of painting devoted to America's current social eruptions. Within the Whitney, the painting exists within a larger social dialogue.

Lew explains his real experience of viewing the painting: "For me, whenever I’m standing in front of the painting, it brings about a real sense of loss. It really evokes the feeling of mourning for a real person who has died. It was that feeling, when I saw it for the first time in Dana’s studio, that allowed me to think about the painting in a way that would fit into the Biennial, within a constellation of artworks that could speak to these issues in a deeply meaningful and deeply sad and empathetic way . . . "

Hannah Black Letter & Petition

Addressing Hannah Black's petition (and letter to the museum, which we published in its entirety calling for the destruction of 'Open Casket', Lew is unyielding in his defense of not responding. "As a museum with a collection, with the role of being custodians for art, we can never condone the destruction of a work. It’s such an extreme demand that it brings things to the point where one can’t have a real conversation."

Marilyn Minter, a leading liberal and feminist voice on the New York arts scene, a person we have followed for years and is now a leading Trump critic, posted on Facebook: “The art world thinks Dana Schutz is the enemy? The left is eating its young again. Censorship from the left really sucks!”

If we do not see the humanity in one another, that’s when we end up with divisions and barriers. In many ways, it goes back to when we could only see 3/5 of a person. That’s what has led us down this path to where we can no longer empathize or even speak to each other. To police these barriers takes us down a dangerous path, moving us away from the very ideals of what this country can be.

Artist Hannah Black. Courtesy of the artist and MOMA PSI

In an equally sober reflection, Lew addresses an issue that we find to be relevant within the controversy:

The other thing about the work—the history that Dana is tapping into with the work, the lynching and murder of Emmett Till—is that this is a history that is an American history. Certainly people of different races have different experiences, but this historic and contemporary violence is something that we all have to grapple with and confront. It is deeply painful and traumatic—more so for some than others, in unequal terms—but it is something that we all have to deal with, and I think if we don’t confront it, if we don’t have these kind of conversations, then we’re not getting anywhere.

Schutz herself speaks to this reality, saying the painting is "not a rendering of the photograph but is more an engagement with the loss." Note that the actual open-casket photographs of Emmett Till are horrific beyond our understanding of human's capacity for torturous violence.

NBC writes that Schutz made the painting in August of 2016 during a time which she calls "a state of emergency" that came about as a result of fatal officer involved shootings of unarmed Blacks. She believes the violence Till experienced coincides with violence and brutality innocent Black men face today.

Why Not Paint Emmett Till From A White Woman's POV?

Art professor Dr. Lisa Whittington, a Black artist who has created two paintings of Emmett Till, takes no issue with a white artist taking on the difficult subject matter, but questions Schutz's perspective in making the painting. This seems like a valid question to us and one worth exploring.

"I would ask her, why she did not paint the Emmett Till Story from a white woman's point of view? Is there nothing that as a white woman that she would want to say? Especially in recently knowing that the woman who accused Emmett Till has admitted that she lied. Where is the artwork that represents her lies?" Whittington said. "The two men who lynched Emmett? Where is the artwork about them? Does she have nothing to say there?"

Whittington continued, "As artists—responsible artists—we are to speak and to document history. We are to tell about life from our point of view from where we stand."