What Elephant Crop Raids in Kenya's Masai Mara Are Telling Us About Future Conflict

/Top: David Clode on Unsplash; Bottom: The Cattle Economy of the Maasi, National Geographic by Ton Koene

By Lydia Tiller and Bob Smith. First published on The Conversation.

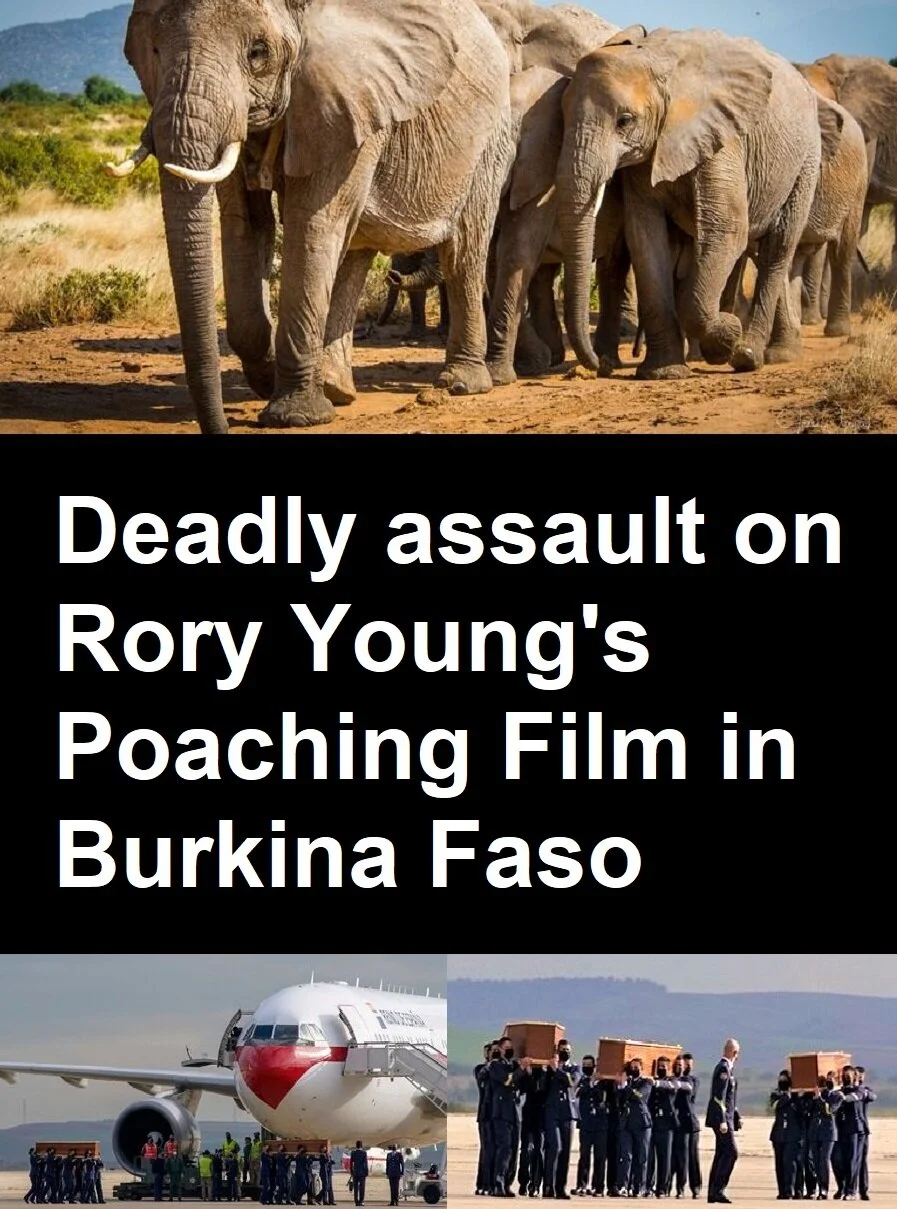

The Masai Mara ecosystem, in south-western Kenya, is home to an important elephant population of about 2,500 individuals.

Elephants need large amounts of space to roam in search of food and water. Because of this, they often move outside the boundaries of protected areas – such as the Masai Mara National Reserve and wildlife conservancies – into areas where people live.

These people are impacted by elephants that eat and destroy farm crops. Sometimes their lives are threatened. This often creates fear and anger towards this species and sometimes leads to elephants being killed in retaliation.

These negative interactions – termed human-elephant conflict – pose a huge threat to populations of this endangered species.

We carried out research on trends of elephant crop-raiding on the western border of the Masai Mara National Reserve. The human population in this region has grown quickly, partly through new people arriving to farm, leading to rapidly changing land-use and high human-wildlife conflict.

We wanted to understand whether, over 15 years, patterns of elephant crop raiding had changed.

We found that there were big changes. Crop raiding was happening more often, in different places and at different times of the year. In addition, the number of elephants killed in retaliation had also increased.

We believe that these patterns signal that elephants in the area are being affected by the expansion of farmland. This creates a cycle in which elephants then negatively affect people.

Our findings are a classic example of what is occurring across much of Africa: rapid habitat loss and increasing conflict. Thus, there is a pressing need to monitor and understand changes. This would help to inform mitigation strategies and move from conflict to coexistence.

More human-elephant conflict

We collected data on incidents of human-elephant conflict between 2014 and 2015. When an elephant ate someone’s crops, broke a fence, damaged property or caused human injury or death, we recorded it. We also checked the number of elephants involved in each incident by measuring footprints and dung.

We then compared this data with a similar study from 1999 to 2000. This provided us with insights into long term trends.

There were important changes in elephant crop raiding patterns since 2000. The number of crop-raiding incidents increased by 49%, but crop damage per incident dropped by 83%.

In addition, the elephants were raiding closer to the protected area and raids were unpredictable. They happened all year round rather than seasonally, when crops are ripe.

Tracking incidents

We have several theories for this behaviour.

Elephants could be carrying out more raids because there is less for them to eat in the protected area. This is due to people increasingly breaking the rules by taking their livestock to graze inside the national park.

There could be less crop damage because farmers are better at scaring elephants away. They do this using well-established techniques, such as making noise, using flash lights, fire crackers and fire.

Elephants could be raiding closer to protected areas because of changes in land cover. There’s less forest (due to illegal charcoal clearing) and more farmland. This makes it harder for elephants to hide.

Widespread conflict

Left: mar is sea Y on Flickr; David Clode on Unsplash.

While the total amount of crop damage has fallen, there are more farms and more people being impacted. Between 1999 and 2000 there were 263 crop-raiding incidents per year. This increased to 392 incidents between 2014 and 2015. Crop-raiding also happens for longer periods during the year.

This could explain why the illegal killing of elephants due to conflict in our study area increased during the study period, nearly doubling from five elephants in 1999/2000 to nine in 2014/2015.

There are a few things that are needed to address the changes in crop-raiding patterns and, in turn, reduce human-elephant conflict.

Conservation management must be improved to protect the elephants’ food base and reduce disturbances within protected areas. For instance, authorities must do more to address the many cattle that illegally graze in the reserve. The number of livestock within the Masai Mara has increased more than tenfold in the last few decades, from around 2,000 in the 1970s to 24,000 in the 2000s.

Communities around the Masai Mara National Reserve must see the benefits of protecting and conserving wildlife. There’s a legal requirement that residents of the area should receive a percentage of the park revenue each year from the county government. At the moment, almost none of this money goes into the pockets of local communities. This helps explain why the rules about cattle grazing are so widely broken.

In addition, policymakers and conservation practitioners must work with local communities on the frontline to help inform mitigation strategies and build tolerance towards wildlife.

Lydia Tiller: Research and Science Manager at Save the Elephants and Associate, Durrell Institute for Conservation and Ecology, University of Kent

Bob Smith: Director, Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology, University of Kent

![Into-the-Okavango_[Neil-Gelinas]_3-dbl.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55f45174e4b0fb5d95b07f39/1561937163642-AJXZW3I471QGTYL0AE03/Into-the-Okavango_%5BNeil-Gelinas%5D_3-dbl.jpg)