A Wild Species Coffee Bean Could Save Our Premium Taste Daily Brew Addiction

/By Aaron P David, Senior Research Leader, Plant Resources, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. First published on The Conversation

The world loves coffee. More precisely, it loves arabica coffee. From the smell of its freshly ground beans through to the very last sip, arabica is a sensory delight.

Robusta, the other mainstream coffee crop species, is almost as widely traded as arabica, but it falls short on flavour. Robusta is mainly used for instant coffee and blends, while arabica is the preserve of discerning baristas and expensive espressos.

Consumers may be happy, but climate change is making coffee farmers bitter. Diseases and pests are becoming more common and severe as temperatures rise. The fungal infection known as coffee leaf rust has devastated plantations in Central and South America. And while robusta crops tend to be more resistant, they need plenty of rain – a tall order as droughts proliferate.

The future for coffee farming looks difficult, if not bleak. But one of the more promising solutions involves developing new, more resilient coffee crops. Not only will these new coffees have to tolerate higher temperatures and less predictable rainfall, they’ll also have to continue satisfying consumer expectations for taste and smell.

Finding this perfect combination of traits in a new species seemed remote. But in newly published research, my colleagues and I have revealed a little-known wild coffee species that could be the best candidate yet.

Coffee farming in a warming world

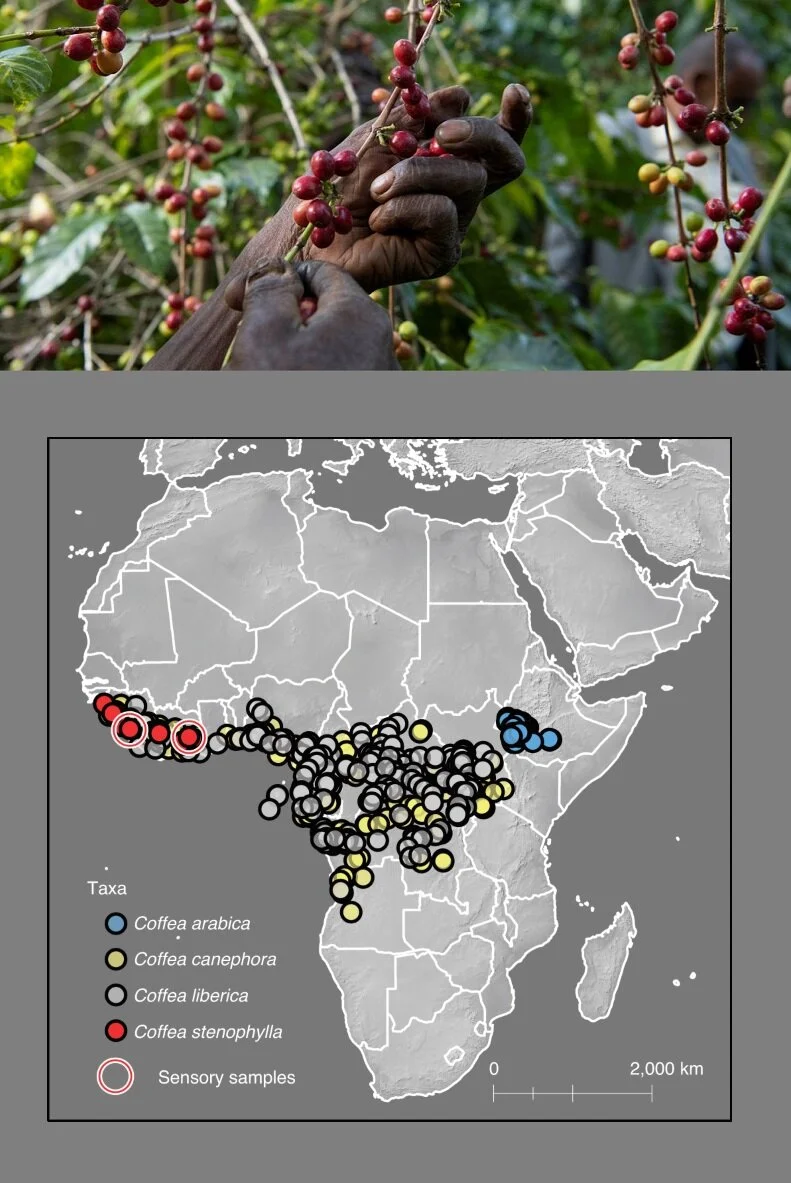

Coffea stenophylla was first described as a new species from Sierra Leone in 1834. It was farmed across the wetter parts of upper west Africa until the early 20th century, when it was replaced by the newly discovered and more productive robusta, and largely forgotten by the coffee industry. It continued to grow wild in the humid forests of Guinea, Sierra Leone and Ivory Coast, where it became threatened by deforestation.

At the end of 2018, we found stenophylla in Sierra Leone after searching for several years, but failed to find any trees in fruit until mid-2020, when a 10g sample was recovered for tasting.

Field botanists of the 19th century had long proclaimed the superior taste of stenophylla coffee, and also recorded its resistance to coffee leaf rust and drought. Those early tasters were often inexperienced though, and our expectations were low before the first tasting in the summer of 2020. That all changed once I’d sampled the first cup on a panel with five other coffee experts. Those first sips were revelatory: it was like expecting vinegar and getting champagne.

This initial tasting in London was followed by a thorough evaluation of the coffee’s flavour in southern France, led by my research colleague Delpine Mieulet. Mieulet assembled 18 coffee connoisseurs for a blind taste test and they reported a complex profile for stenophylla coffee, with natural sweetness, medium-high acidity, fruitiness, and good body, as one would expect from high-quality arabica.

In fact, the coffee seemed very similar to arabica. At the London tasting, the Sierra Leone sample was compared to arabica from Rwanda. In the blind French tasting, most of the judges (81%) said stenophylla tasted like arabica, compared to 98% and 44% for the two arabica control samples, and 7% for a robusta sample.

The coffee tasting experts picked up on notes of peach, blackcurrant, mandarin, honey, light black tea, jasmine, chocolate, caramel and elderflower syrup. In essence, stenophylla coffee is delicious. And despite scoring highly for its similarity to arabica, the stenophylla coffee sample was identified as something entirely unique by 47% of the judges. That means there may be a new market niche for this rediscovered coffee to fill.

Breaking new grounds

Until now, no other wild coffee species has come close to arabica for its superior taste. Scientifically, the results are compelling because we would simply not expect stenophylla to taste like arabica. These two species are not closely related, they originated on opposite sides of the African continent and the climates in which they grow are very different. They also look nothing alike: stenophylla has black fruit and more complex flowers while arabica cherries are red.

It was always assumed that high-quality coffee was the preserve of arabica – originally from the forests of Ethiopia and South Sudan – and particularly when grown at elevations above 1,500 metres, where the climate is cooler and the light is better.

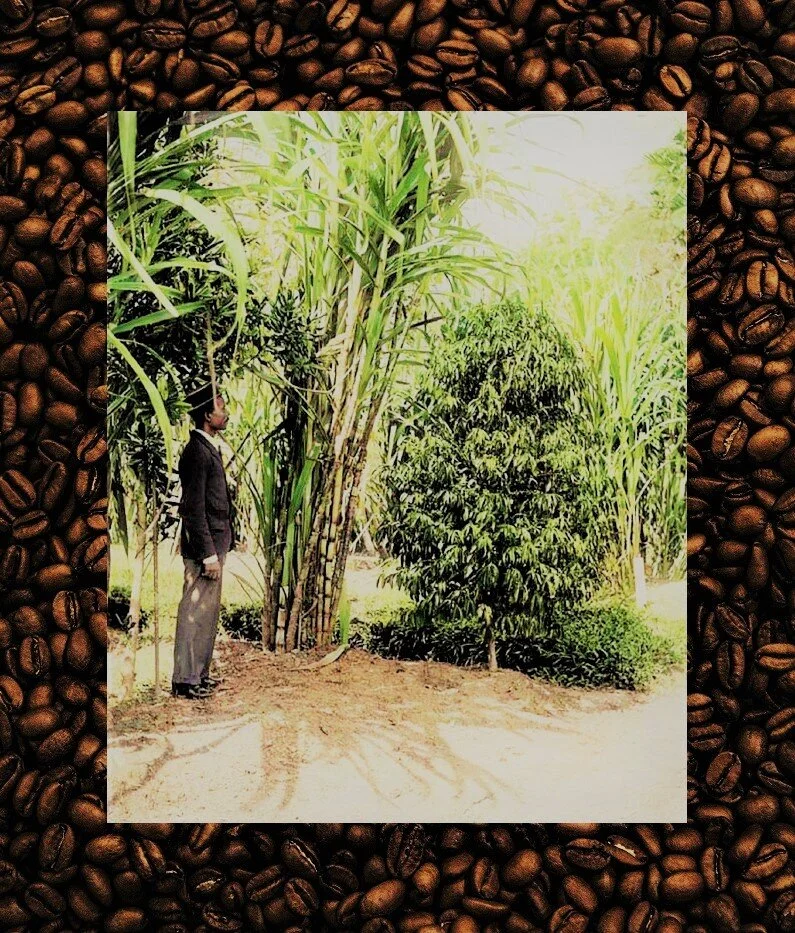

Stenophylla coffee breaks these rules. Endemic to Guinea, Sierra Leone and Ivory Coast, stenophylla grows in hot conditions at low elevations. Specifically it grows at a mean annual temperature of 24.9°C – 1.9°C higher than robusta, and up to 6.8°C higher than arabica. Stenophylla also appears more tolerant of droughts, potentially capable of growing with less rainfall than arabica.

Robusta coffee can grow in similar conditions to stenophylla, but the price paid to farmers is roughly half that of arabica. Stenophylla coffee makes it possible to grow a superior tasting coffee in much warmer climates. And while stenophylla trees tend to produce less fruit than arabica, they still yield enough to be commercially viable.

To breed the coffee crop plants of the future, we need species with great flavour and high heat tolerance. Crossbreeding stenophylla with arabica or robusta could make both more resilient to climate change, and even improve their taste, particularly in the latter.

With stenophylla’s rediscovery, the future of coffee just got a little brighter.

![Into-the-Okavango_[Neil-Gelinas]_3-dbl.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55f45174e4b0fb5d95b07f39/1561937163642-AJXZW3I471QGTYL0AE03/Into-the-Okavango_%5BNeil-Gelinas%5D_3-dbl.jpg)