The Dark Side of Our Fashion Industry: Drug Abuse

/David Bailey Heroin Chic Freshly Worn Magazine 2013

By Thanush Poulsen

The fashion industry is notorious for the atmosphere of glamour, rush, and partying that surrounds it. Designers, models, and stylists appear to have the lives that a lot of people dream about: fulfilling, vibrant, and gleaming. All the shine, however, is just the tip of the iceberg. Beneath it are thousands of work hours, overwhelming stress, and pressure that only increase as we go deeper into the field.

It’s not surprising that many people try coping with such enormous load through means that are no less extreme. Drug abuse, in particular, is incredibly common in the fashion industry. The use of illicit drugs and the misuse of prescription medicines are often regarded with no judgment whatsoever. At the same time, it’s easy to get blinded by the sparkling facade and miss the massive normalization of drug abuse in the industry. Many people prefer focusing on the sterile beauty that fashion represents, rather than on the ugly truth. Such lack of concern promotes denial of the condition and makes a person less likely to seek treatment.

Those who do realize they have a problem and want to get help don’t have it easy either. Living in the spotlight, constantly followed by fans and cameras that record your every move, is stressing, even for those who don’t abuse drugs. The news about addiction goes viral extremely quickly and can inflict an avalanche of public humiliation on a celebrity. It makes finding the right facility to get treatment twice as hard due to concerns for confidentiality. For this reason, it’s hard to overestimate the impact a single private rehab center (navigate here) can have on a person’s life.

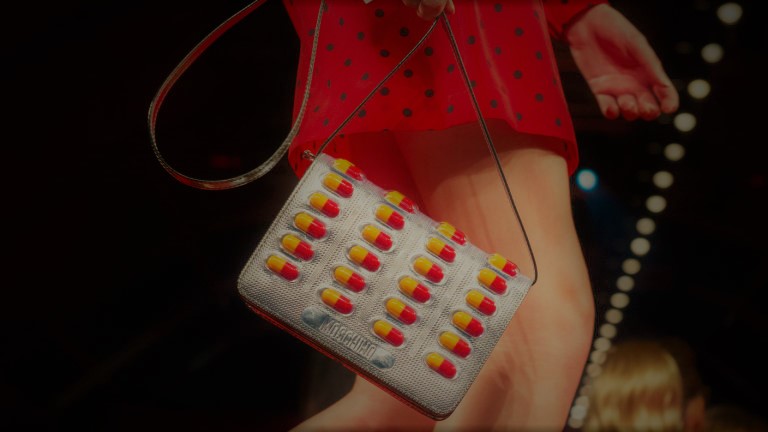

Handbag from Moschino AW 2016. Much of the collection was pulled from stores.

The Role of Drugs in the Fashion Industry

There is no denying that drug abuse has infiltrated the fashion industry a long time ago. To make matters worse, the views on drugs within the industry tend to fluctuate. One day, the abuse gets swept under the rug; a month later it’s the center of everybody’s attention. The truth, however, is entirely stable and quite grim – for those who choose to acknowledge it. As a seasoned stylist and fashion editor George Cortina said on the matter of substance addiction, “if you don’t see it everywhere in fashion, you’re wearing a blindfold.”

Along the same lines, model Sophie Anderton, who suffered from cocaine addiction for years before giving it up, told the Independent that “drugs are so accessible within the industry, and it is very difficult to steer completely clear of them.” During rehabilitation, patients go through therapy to learn how to deal with triggers and prevent relapsing. They are also advised to avoid high-risk situations and environments where they might be tempted to use again for some time after leaving rehab. In the fashion industry, a simple decision to put an end to one’s substance addiction is not enough, since drugs can always be easily obtained.

Still, although availability plays a major role in a person’s choice to use drugs, the industry with all its flaws is not necessarily the greatest evil, according to a widely known and accomplished designer Calvin Klein. “Addiction is not caused by stress on the job,” Klein said, “even though lots of people in the fashion industry have suffered from the same problem. It has more to do with your childhood and lots of other things.”

Nearly 2.6 million people in the United States enter private drug treatment every year. For some, the industry is just a catalyst; many others get dragged into substance abuse by struggles, brought on by their jobs. One of such struggles is, understandably, extreme tension. A normal workday during events like New York Fashion Week frequently exceeds twelve hours. Models and stylists are expected to be at their best despite exhaustion and sleep deprivation. Stimulant drugs like cocaine help cope with the stress and fatigue, pull all-nighters, and be outstanding on a catwalk or in a studio for as long as it is required.

Poor self-esteem, body image, and representation all add up to the issues that runway models have to work through. They are obliged to stay skinny and fit, and any deviations from this highly valued waif-like appearance may result in lost contracts and damage to a model’s career. Naturally, such conditions make it barely possible to have a healthy attitude towards your body.

Race is another factor that determines how a model is likely to be treated within the industry and what effect it’s going to have on them. For instance, women of color were found to have a generally better body image and less body dissatisfaction relative to their Caucasian counterparts, which makes white women more susceptible to illicit and prescriptions drug abuse. At the same time, less than 25% of the models cast in autumn 2016 were models of color, although progress is being made on this issue.

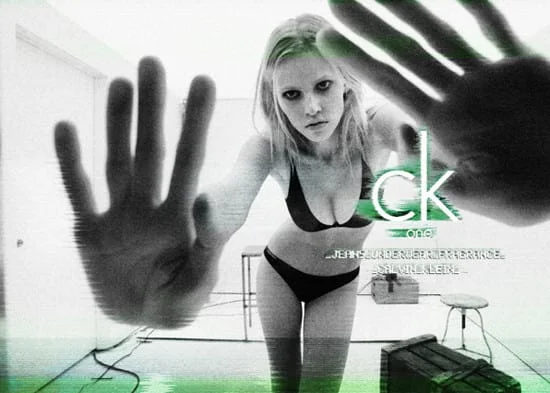

This 2011 calvin klein image of model Lara Stone was taken after her 2009 rehab stay to overcome an alcohol addiction.

Cocaine and weight loss

Cocaine occupies a special place within the fashion industry. It’s a powerful stress reliever, and it changes the body’s metabolism in a way that keeps a person skinny regardless of what they eat. In the environment where body shape and weight play a major, sometimes life-turning role, it shouldn’t come as a surprise to see people sacrificing their health for good looks.

Cocaine targets the central nervous system and acts as a stimulant by promoting the release of neurotransmitters like dopamine and noradrenaline. Dopamine is responsible for the feeling of pleasure, while noradrenalin ensures your physical readiness to act in a high-stress situation. It increases blood pressure, makes your heart race, and induces a state of euphoria. Cocaine makes people feel more alert, confident, and brave. As a result, it’s frequently abused before important shows, presentations, and runway walks.

Cocaine is also seen as a tool to lose weight quickly. While CNS stimulants do contribute to obesity and the development of various eating disorders, this property is in fact real. In the past, it was attributed mainly to stimulants’ tendency to suppress your appetite, though that theory shattered when it was found that cocaine users tend to eat more fatty foods and drink more alcohol, which is normally associated with weight gain. Despite these behaviors, however, cocaine users statistically have less fat mass than those who don’t abuse drugs.

Turns out, noradrenaline that decreases your appetite also has another more important function. Along with dopamine, it’s involved in the breakdown of stored fat, called lipolysis. When lipolysis occurs faster than usual, a person loses fat mass. It’s also one of the aspects that make it so important to handle cocaine withdrawal at private rehabilitation clinics instead of going through it on your own since the rapid weight gain associated with it can be quite harmful to health.

Image Source

The Rise and Fall of ‘Heroin Chic’

The fashion industry has always been one of the most influential forces that shaped the way people looked, dressed, and lived their lives. Still, despite its creative and defining nature, fashion is also steered towards innovation by trends and tendencies of its time. It is, therefore, quite difficult to imagine an advertising campaign that endorses drug abuse being successful in 2019. These days, the world embraces self-care and promotes awareness of the detrimental effects of substance addiction. These days, a healthy lifestyle is popular.

It wasn’t nearly the case at the beginning of the 90s, however. While drug abuse was never openly encouraged by the fashion industry or media, several factors coincided to create a comfortable and enabling environment for the popularization of drugs. First of all, the enormous stigma surrounding substance abuse and heroin, in particular, triggered by the AIDS epidemic, began to ease off. Heroin became significantly cheaper and purer, which allowed users to snort it instead of injecting it with potentially unclean needles. The decreased mindfulness resulted in heroin no longer being attributed solely to the poor but spreading out and infecting the middle class as well. At the same time, a new direction in the fashion industry appeared, pointed by photographers like Corinne Day, Juergen Teller and Craig McDean. The look of models on their photographs was raw, natural, defiant of the glamour of the 80s.

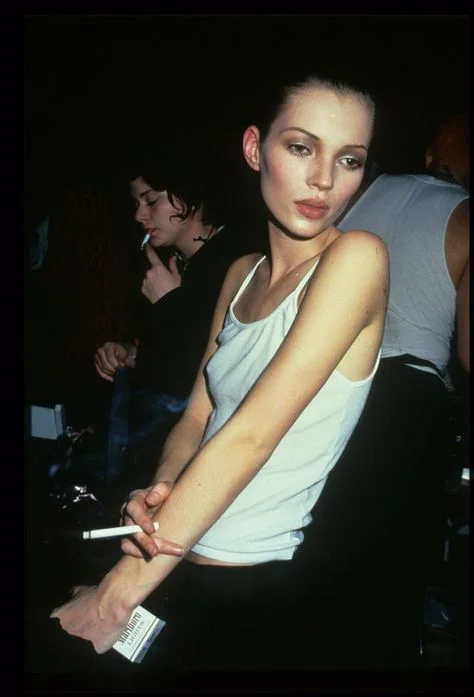

Kate Moss, back in the day as the famous heroin chic fashion industry body.

The availability of drugs and the new rebellious course in modeling and photography gave rise to ‘heroin chic’ – a trend that quickly grew into a whole culture. The look was characterized by pale skin, sharp bones, skinny body, and dark circles under the eyes. Models posed with their hair ungroomed, wearing minimal or carelessly applied makeup and looking as true as they could ever be. As Corinne Day described herself, it was “all about freedom, really – and being proud of the holes in your jumper.”

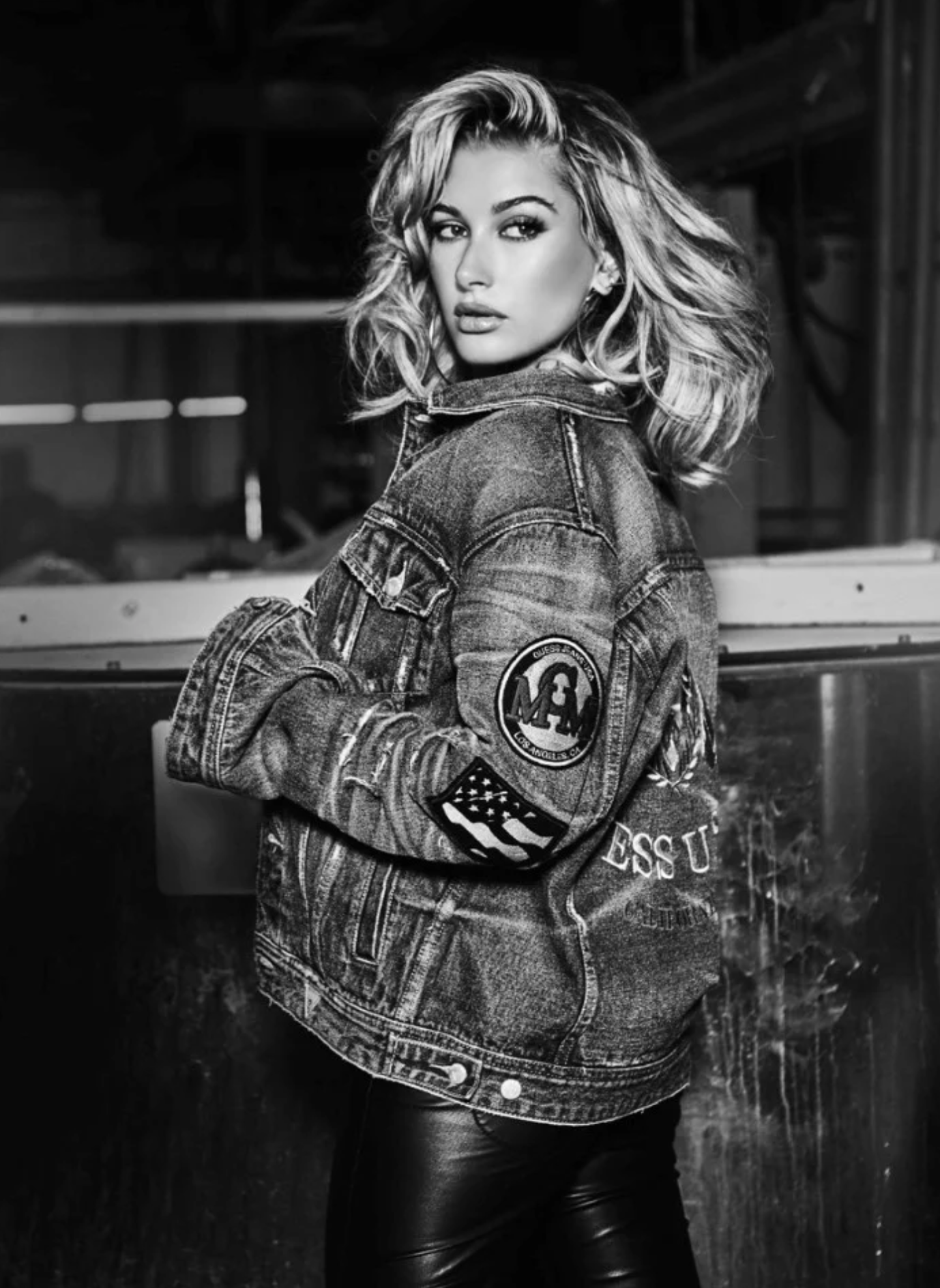

Stunned by the looks of several prominent models of that time, including Kate Moss, Jaime King, Drew Barrymore, and Jodie Kidd, the world quickly accepted the ‘heroin chic,’ and the fashion industry turned into a hotbed of drug abuse. Designers like Calvin Klein exploited the trend in their advertisings, contributing to glamorization of drugs. CK ads, in particular, featured extremely sexualized teenage models along with daring slogans that were met with a lot of controversies andyet managed to create an image of a lifestyle that was incredibly alluring to the youth.

Fortunately, the ‘heroin chic’ was a short-lived phenomenon. Following the death of Davide Sorrenti in 1997, several anti-drug statements were made by representatives of the fashion industry, media, and the American government. Sorrenti was a famous young photographer and an active proponent of the ‘heroin chic’ look in his art. His death at the age of 20 after heroin overdose was a wake-up call, loud enough for the public to finally take notice.

On May 21, 1997, US President Bill Clinton spoke to 35 big-city mayors on the matters of US drug policy and accused the ‘heroin chic’ trend of making drugs seem “glamorous, sexy, and cool.” “The glorification of heroin,” Clinton added, “is not creative, it’s destructive. It’s not beautiful; it’s ugly. And this is not about art; it’s about life and death. And glorifying death is not good for any society.”

Later that year, thirteen leading designers, including John Galliano, Stella McCartney, John Rocha, Reynold Pearce, and Andrew Fionda, signed a statement condemning the industry’s use of drugs to promote fashion. They expressed their concern about “the waste of human potential caused by substance addiction” and claimed to “disapprove of the fashion industry glamorizing the use of addictive substances, as this could have a detrimental effect on the lives of young people, many of whom are greatly influenced by the appearance and actions of members of our industry.

Recovery Is Possible

Photo by pawel szvmanski on Unsplash

In subsequent years after the ‘heroin chic’ craze began to fade, private rehab facilities all over the country experienced an increased influx of clients. Although the trend took its toll, destroying lives, and crashing careers, it also stimulated a lot of models, artists, and designers to address their addiction. Some did it openly, others discretely, but the message was clear: substance abuse is an alarming issue that can, however, be overcome.

The level of awareness inside the fashion industry leaped in 2003, when Calvin Klein himself decided to reveal his struggles with alcohol and prescription drug addiction. Klein entered private rehab in the 80s for the first time and opened up about his addiction after an incident caused by his erratic behavior during a Knicks basketball game almost 15 years later.

“For many years, I’ve been able to successfully address my substance abuse issues, which for anyone is a lifelong process,” Klein admitted in a statement, “through strict adherence to counseling and regular attendance at meetings. However, when I recently stopped attending meetings regularly, I suffered a setback. Fortunately, I was lucky with the help of others to recognize the problem. And now, I’m again getting the treatment I need to resume a healthy and productive lifestyle.”

Although the days of the ‘heroin chic’ are now in the past, the contemporary culture of concealed abuse is no less devastating. It’s fueled by ignorance and blindness of those who are afraid to face what’s lurking under the rug. No progress can be made until the industry acknowledges the issue and confronts the established attitude, mindset, and acceptance. Maybe it’s time for fashion to slow down, look closely at the cost of beauty that it dictates and finally bring drug abuse into the spotlight.

About the Author

Thanush Poulsen is a Danish journalist who reviews and investigates the health issues in the public and private fields of social life, how the image of “being healthy” changes over time, and how all health-related trends affect our lives.