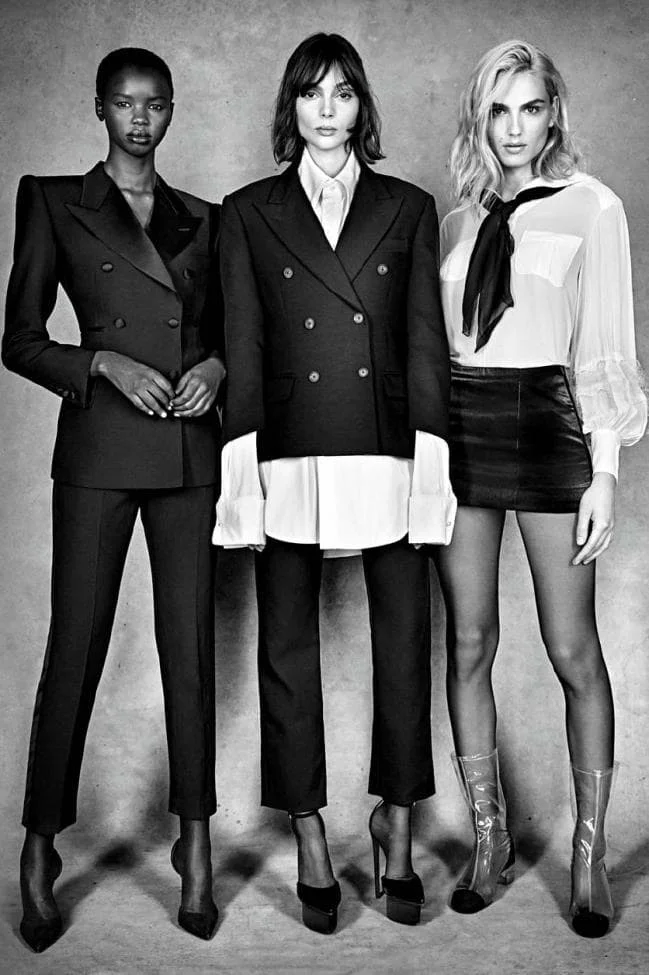

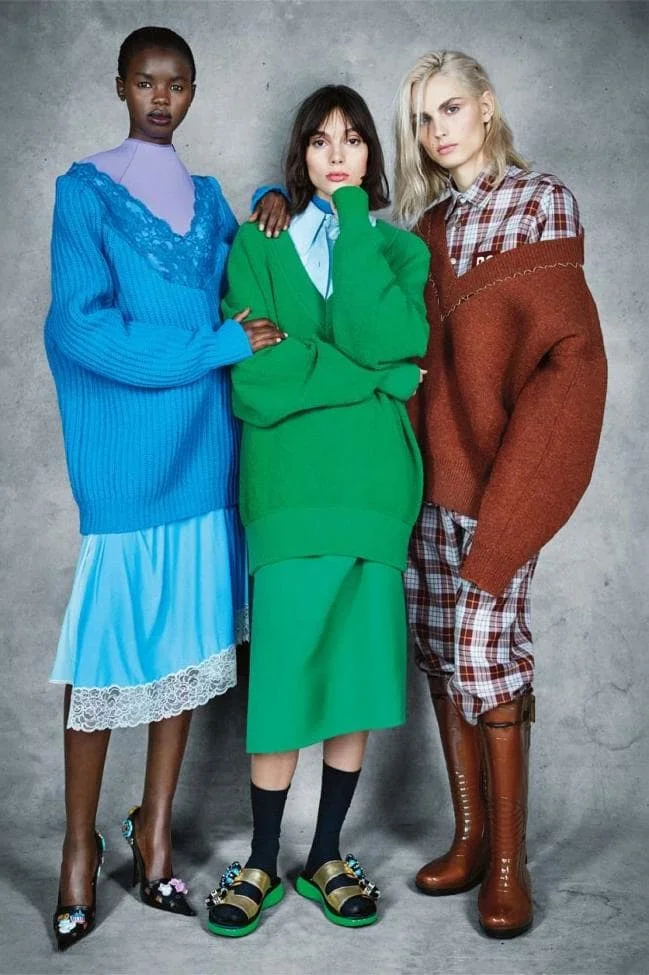

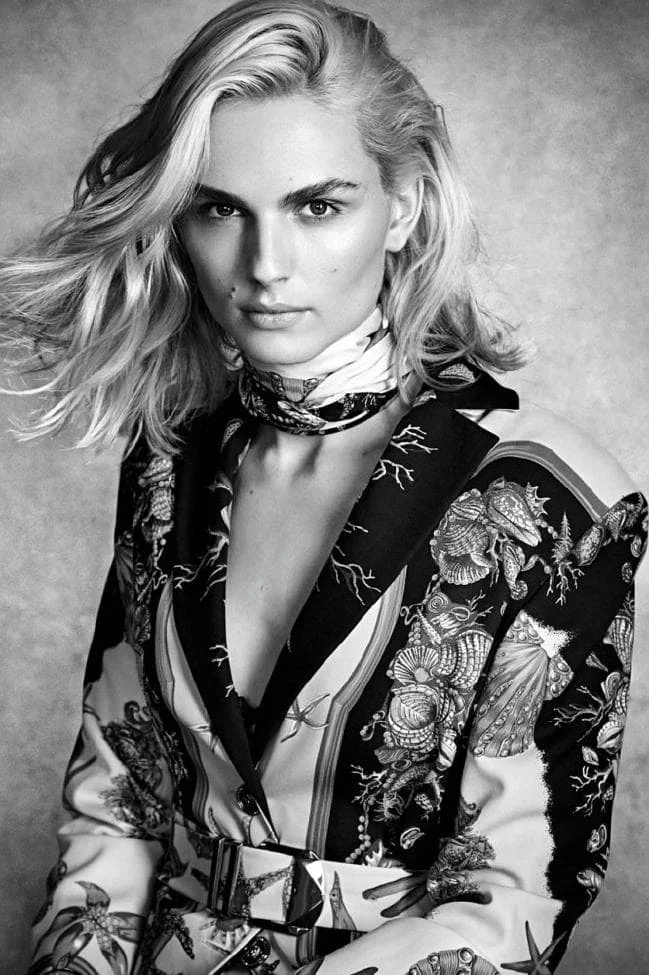

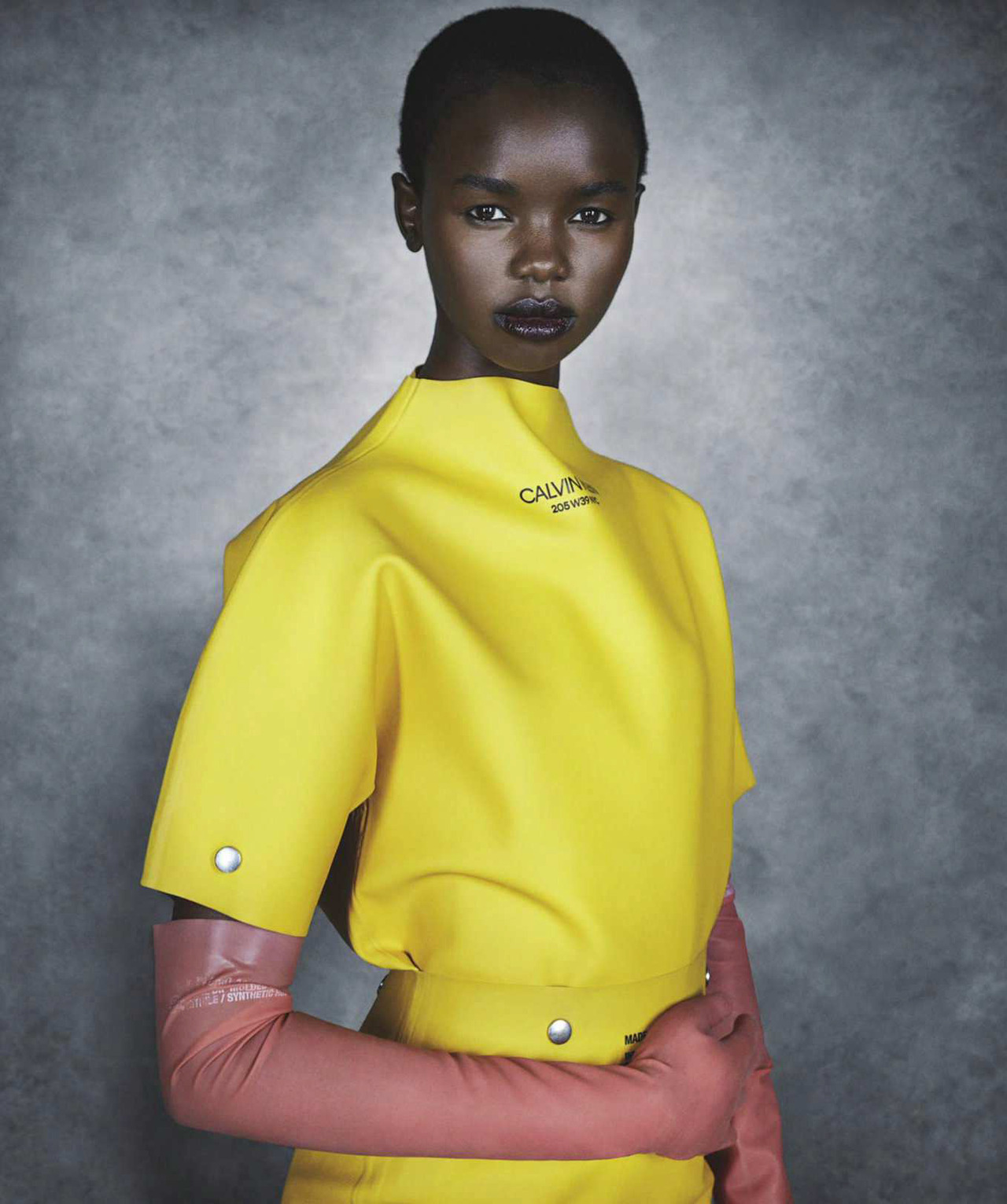

Akiima, Charlee Fraser, Andreja Pejic & Fernanda Ly Promote Diverse Faces Of Australian Fashion

/Models Akiima, Charlee Fraser, Andreja Pejic and Fernanda Ly cover the April 2018 issue of Vogue Australia, lensed by Patrick Demarchelier, posing as people first and fashion models second. The quartet pens pwerful and personal stories for the issue, with their histories highlighted before their favorite face savers. Still, the cover story promotes them as 'The Faces Uniting Australian Fashion'.

Vogue Australia's editor-in-chief Edwina McCann says of the issue: "“It felt timely to celebrate that fact, because it truly reflects who we are. Despite being a multicultural country, we have long subscribed to a homogenous standard of beauty. Charlee Fraser, Akiima, Fernanda Ly and Andreja Pejić prove that thinking – and casting – is archaic.”

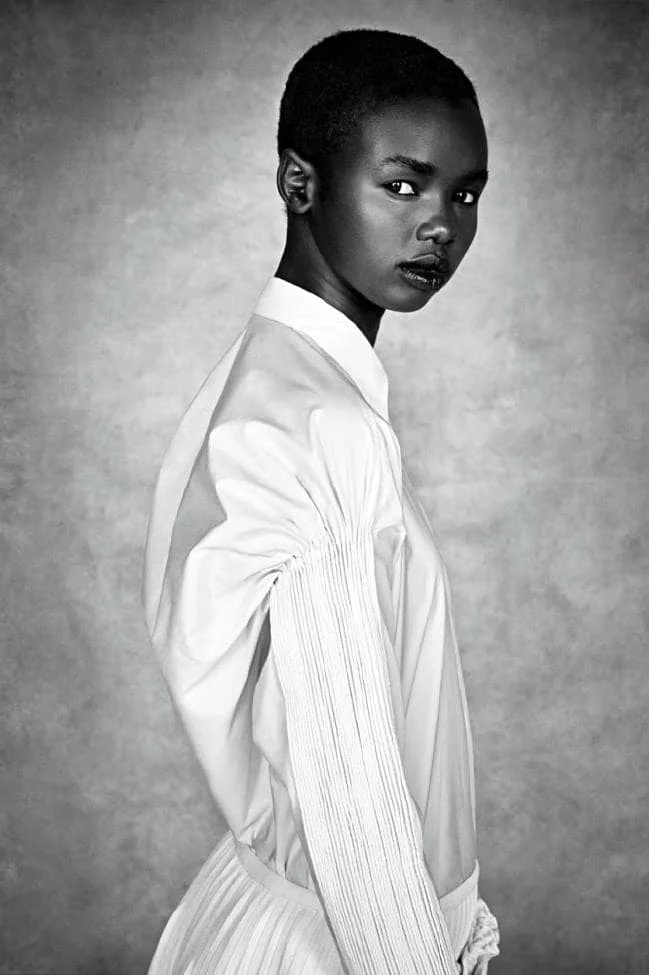

Akiima hails from Adelaide and was born in a war-ravaged village in South Sudan before transiting to a Kenyan refugee camp. She writes: “Unfortunately we don’t get to see the diversity of Australian beauty. We have come a long way, but we still need to discuss diversity in the modelling industry … because we don’t want to keep asking for a spotlight.”

Trans model Andreja Pejić says that the fact that her body is presented as an unrealistic ideal of ‘beauty’ to the world doesn’t stop her, along with most other models, from feeling insecure about themselves. “Adding to this is the fact that I am also a trans person, a war refugee, and that my long-lost father doesn’t drive a Rolls-Royce and my mother is not a former Hollywood actress with status and fame. In light of this, I have plenty of reasons to wonder: ‘How the fuck did I get here?’” But of her Vogue cover, shared with three other Australian beauties, she writes: “The idea is simple, but clear and important: we’re all different, but still the same.”

Charlee Fraser runs head-on into the topic of perceptions of beauty. “We’re slowly turning a page in the book of time and beginning to perceive beauty in all forms of race and colour. People often ask me what it’s like to be a role model for young Indigenous women and I often don’t know how to respond. I guess it’s because I’ve never sat down and thought of myself in those terms.”

Fernanda Ly, asks the most direct question -- but also one that plays both ways. "Must there always be a bracketed 'Australian-born Chinese?' . . . Why not stop with merely ‘Australian’? … racial dysphoria is a concept I am constantly struggling with … Cultural heritage does not simply disappear … I feel like an eternal floater. I was raised in what I would consider to be a disjointed mess of Australian, Chinese and Vietnamese upbringing.”

This question plays both ways because the increasinglt tighter noose around the idea of cultural appropriation can also be stifling, not allowing people to morph into new identities or even experience a new look 'foreign' to their own self-image.

"Why can't I just be 'Australian'?" Fernanda asks. Most of us have no problem condemning white majority populations for being exclusive in their cultural vision of so-called white identity and power, while we simultaneously trash them for infringing in any way on cultural identities that belong to others and, in particular, people of color. It's an interesting paradox in my opinion, and I'm not sure we can have it both ways. Peoples brains are not wired that way. ~ Anne