The Evolution of the Medieval Witch – and Why She’s Usually a Woman

/Related: ‘The Witches of Salem’ by Stacy Schiff for The New Yorker

By Jennifer Farrell, Lecturer in Medieval History, University of Exeter. First published on The Conversation.

Flying through the skies on a broomstick, the popular image of a witch is as a predominantly female figure – so much so that the costume has become the go-to Halloween outfit for women and girls alike. But where did this gendered stereotype come from? Part of the answer comes from medieval attitudes towards magic, and the particular behaviours attributed to men and women within the “crime” of witchcraft.

Taking one aspect of the witch’s characterisation in popular culture – her association with flight – we can see a transformation in attitudes between the early and later Middle Ages. In the 11th century, Bishop Burchard of Worms said of certain sinful beliefs:

Some wicked women, turning back to Satan and seduced by the illusions and phantasms of demons, believe [that] in the night hours they ride on certain animals with the pagan goddess Diana and a countless multitude of women, and they cross a great span of the world in the stillness of the dead of night.

According to Burchard, these women were actually asleep, but were held captive by the devil, who deceived their minds in dreams. He also believed that none but the very “stupid and dim-witted” could think that these flights had actually taken place.

But by the end of the 15th century views of magic had changed considerably. While many beliefs about women flying through the skies persisted, the perception of them had transformed from one of scepticism to one of fear. The magic night flight became associated with secret gatherings of witches known as “the sabbath”, involving nefarious acts such as killing babies, taking part in orgies and worshipping the devil.

This suggests that what was originally considered to be a belief held only by women and foolish men was now being taken much more seriously. So what happened to cause such a transformation?

One explanation offered by historian Michael D. Bailey is that at some point during the 14th and 15th centuries, religious officials perhaps unwittingly conflated two distinct traditions: “learned” magic and “common” magic. The common kind of magic required no formal training, was widely known, could be practised by both men and women, and was usually associated with love, sex and healing.

By contrast, learned magic came to Europe from the east and featured in the “magic manuals” that circulated among educated men whom Richard Kieckhefer described as members of a “clerical underworld”.

Interestingly, descriptions of humans in flight do appear in these manuals – but in relation to men rather than women. One example is found in a 15th century notebook in which the male author describes riding through the skies on a magically conjured “demon-horse”.

Two key differences between this account and the ones associated with women are that the person flying is an educated male and demons are now explicitly involved in the act. By conflating popular beliefs about the night flights of women with the demon-conjuring magic of the clerical underworld, medieval inquisitors began to fear that women would fall prey to the corruption of demons they could not control.

Witchcraft and Women

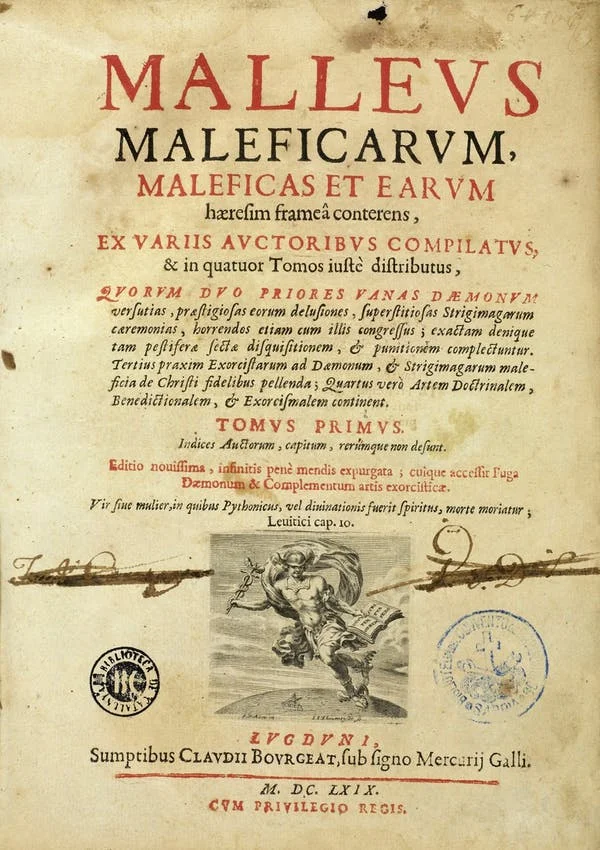

While men also feature in the infamous 15th century witch-hunting manual Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of the Witches), the work has long been recognised as deeply misogynistic. It suggests that women’s perceived lack of intelligence made them submissive to demons. One section reads:

Just as through the first defect in their [women’s] intelligence they are more prone to abjure the faith; so through their second defect of inordinate passions … they inflict various vengeances through witchcraft. Wherefore it is no wonder that so great a number of witches exist in this sex.

By the end of the Middle Ages, a view of women as especially susceptible to witchcraft had emerged. The notion that a witch might travel by broomstick (especially when contrasted with the male who conjures a demon horse on which to ride) underscores the domestic sphere to which women belonged.

The perceived threat to established norms inherent in the idea that women were moving beyond their expected societal roles is also mirrored in a number of the accusations levelled against male witches.

In one example, a 13th century letter by Pope Gregory IX described a gathering of heretics which was very similar to the later descriptions of the witches’ sabbath. It stated that at orgies, if there were not enough women, men would engage in “depravity” with other men. In doing so, they were seen to become effeminate, subverting the natural laws believed to govern sexuality.

Magic was then, in many ways, viewed by the church as an expression of rebellion against established norms and institutions, including gendered identities.

The idea that women might have been dabbling with the demonic magic previously associated with educated males, however inaccurate it may have been, was frightening. Neither men nor women were allowed to engage with demons, but while men stood a chance at resisting demonic control because of their education, women did not.

Their perceived lack of intelligence, together with contemporary notions regarding their “passions”, meant that they were understood as more likely to make pacts of “fidelity to devils” whom they could not control – so, in the eyes of the medieval church, women were more easily disposed to witchcraft than men.