New York Is the First City To Fund Abortion Directly. Let's Make Sure It's Not the Last

/By Alicia Johnson. First published on Rewire.News

Last week, abortion access advocates in New York made history. When the ink dries on next year’s budget, New York will become the first city in the country to directly fund abortion by allocating $250,000 to the New York Abortion Access Fund (NYAAF), which supports anyone who is unable to pay fully for an abortion and is living in or traveling to New York state by providing financial assistance and connections to other resources. This funding will help ensure that every person is able to decide when and whether to become a parent regardless of their income, type of insurance, or citizenship status.

In the face of increasing attacks on abortion access throughout the country, New York City’s commitment to funding abortion sends a powerful message—one that activists in other cities and states can push for.

This is an essential step as we work toward ending the Hyde Amendment, which bans federal funding for most abortions. And we know it won’t be the last: Advocates in progressive cities like ours can seize the opportunity to turn supporters into champions, to advocate for policymakers who talk the talk about abortion access to also walk the walk. Even in progressive states, people face barriers to abortion access. Some people have federal insurance coverage that does not cover abortion care (including members of the military, veterans, and other federal employees), cannot use their insurance for privacy or safety reasons, or cannot afford an abortion despite insurance coverage (such as due to a high deductible). For individuals with low incomes, additional expenses such as travel, unpaid time off work, and child care can push abortion care entirely out of reach, and/or force them to choose between basic necessities (like rent and food) and paying for an abortion. Due to systemic barriers in health care, this especially impacts individuals who are Black, Latinx, immigrants, refugees, or transgender/gender nonconforming.

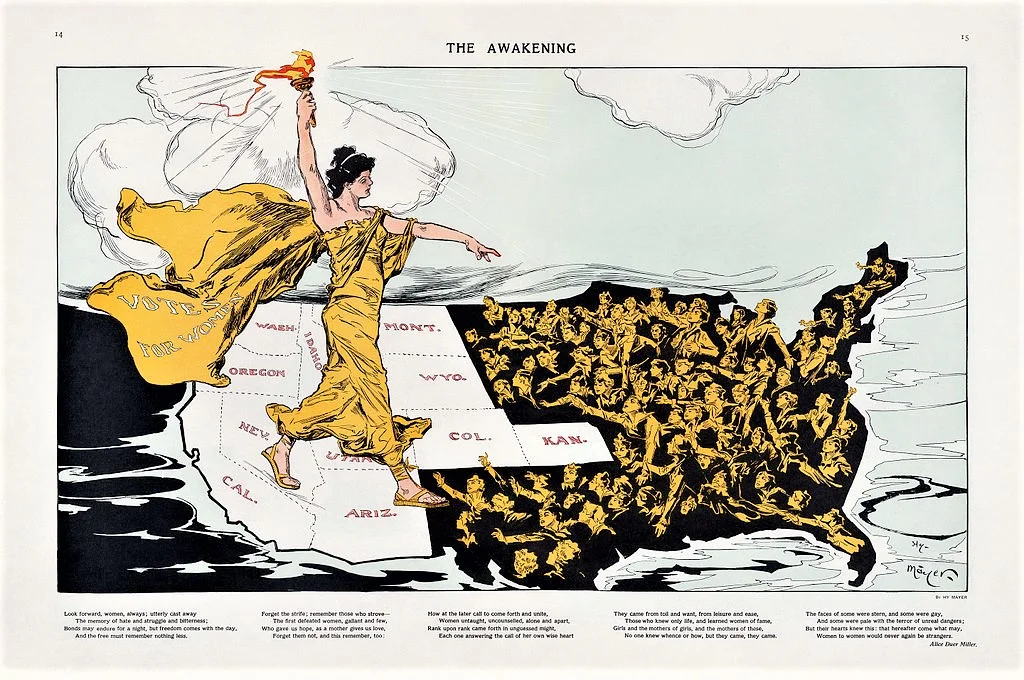

Directly funding abortion care is a concrete action to support people who need abortions and an important statement that the cruel and unjust Hyde Amendment can no longer stand. As New York City Council Member Carlina Rivera tweeted after the funding was announced, “Before Roe v. Wade, NYC was a haven for women who wanted the freedom to choose. It’s time for our City to be that beacon for the country once again.”

We are celebrating this week thanks to a strong coalition of advocates working together to develop a grassroots and political strategy. NYAAF could not have accomplished this victory without the leadership of the National Institute for Reproductive Health (NIRH), the consistent vision and bold messaging of All* Above All, the grassroots mobilization of WHARR: Women’s Health and Reproductive Rights, and the contributions of many others committed to lifting barriers to abortion care.

The Fund Abortion NYC coalition first came together in fall 2018, led by NYAAF and NIRH, to develop a strategy to pursue City Council funding for abortion care. This campaign grew out of informal conversations with the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene about the possibility of funding, which led to the decision to launch an official campaign. With our combined political savvy, grassroots power, communications strategy, and understanding of the abortion funding landscape, we created a powerful force that offered a concrete policy action for policymakers who had long supported abortion access with their words. We found a champion in Council Member Helen Rosenthal, who helped us navigate the City Council budget process. Through lobbying and grassroots mobilization, we laid the groundwork and got our message in front of as many City Council members and citywide elected officials as we could.

New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer at New York City Hall's rally to include abortion care funding in the city's 2020 budget. | Susan Watts/Office of New York City Comptroller Image via City & State New York.

The Fund Abortion NYC coalition built a powerful infrastructure. So when six-week abortion bans in Ohio, Mississippi, and Georgia and a near-total ban on abortion in Alabama galvanized New York policymakers to protect access to local care, we were well poised to connect them to direct action. We are especially grateful to City Comptroller Scott Stringer and Council Members Carlina Rivera and Margaret Chin, the co-chairs of the NYC Council Women’s Caucus, who made abortion funding one of their top priorities in the city budget. NYAAF and the Fund Abortion NYC coalition spoke at rallies, recruited new supporters, circulated a petition with thousands of signers, spoke with the press, and mobilized our base to make calls and send emails to council members.

In the end, the New York City Council was willing to help make abortion a reality for all of us, not just some of us. New York City’s fiscal year 2020 budget will include $250,000 for the New York Abortion Access Fund to support people facing financial and logistical barriers to abortion care.

Politicians and advocates across the country should look to local abortion funds and abortion access advocates to guide the way and identify ways to fund abortion in their own cities and states. We hope New York is just the beginning, and we invite organizers to look to organizations like All* Above All for a justice-oriented vision to repeal Hyde, and the National Institute for Reproductive Health for proactive local policy models.

The momentum to repeal Hyde goes beyond direct abortion funding: In the same week that New York made history by funding abortion, Maine also became the latest state to stand up to the Hyde Amendment by passing a law that requires both public and private insurance that covers prenatal care to also cover abortion care.

Let’s keep up the momentum. Our collective power can shift resources and culture, and create greater access to abortion care.

![Kanye West's [aka Ye] Refusal to Treat His Mental Illness Is No Excuse For His Anti-Semitism](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55f45174e4b0fb5d95b07f39/1666238183530-4WVG9SNG88HTSKQ0WWDV/Is+Kanye-West-Running-Out-of-Platforms.png)