Many Americans Viewed New York Harbor's Lady Liberty as a False Idol of Broken Promises

/A message tacked to the Statue of Liberty after the September 11, 2019 terrorist attack. via

By Angela Serratore. First published on Smithsonian.com as ‘The Americans Who Saw Lady Liberty as a False Idol of Broken Promises’.

It was a crisp, clear fall day in New York City, and like many others, Lillie Devereaux Blake was eager to see the great French statue, donated by that country’s government to the United States as a token of friendship and a monument to liberty, finally unveiled. President Grover Cleveland was on Bedloe’s Island (since renamed Liberty Island), standing at the base of the statue, ready to give a speech. Designed in France, the statue had been shipped to New York in the spring of 1885, and now, in October 1886, it was finally assembled atop its pedestal.

“Presently the veil was withdrawn from her beautiful calm face,” wrote Blake of the day’s events, “and the air was rent with salvos of artillery fired to hail the new goddess; the earth and the sea trembled with the mighty concussions, and steam-whistles mingled their shrill shrieks with the shouts of the multitude—all this done by men in honor of a woman.”

Blake wasn’t watching from the island itself, though—in fact, only two women had been invited to the statue that day. Blake and other members of the New York State Women’s Suffrage Association, at that point New York’s leading women’s suffrage organization, had chartered their own boat in protest of the exclusion of women not just from the statue’s unveiling, but from the idea of liberty itself.

Blake’s protest is one of several highlighted at the new Statue of Liberty Museum, which opened earlier this month on Liberty Island. While the statue’s pedestal did at one point hold a small museum, the new space’s increased square footage allowed historians and exhibit designers to expand the story of Lady Liberty, her champions and her dissenters.

“In certain people's retelling of the statue and certain ways it gets told, it often seems like there's a singular notion, whether it's the statue as a symbol of America or the statue as the New York icon or the statue as the beacon of immigration,” says Nick Hubbard, an exhibition designer with ESI Designs, the firm responsible for the staging of the new museum. But as the newspaper clippings, broadsheets, and images in the space themselves explain, the statue—and what it symbolized—wasn’t universally beloved, and to many, it was less a beacon of hope than an outright slap in the face.

The French bequeathed the statue itself as a gift, but it was up to the people of America to supply it with a pedestal. After both the state of New York and the federal government declined to fund the project, New York World publisher Joseph Pulitzer announced he would use his paper to raise $100,000 (more than $2 million in today’s currency) for the pedestal. The proposition was straightforward: Mail in a donation, get your name printed in the paper. Stories abounded of small children and elderly women sending in their allowances and their spare change, and the heartwarming tales of common folk supporting the grand project captured the front pages of Pulitzer’s paper and the imagination of the country, largely cementing the idea that the Statue of Liberty was, from the beginning, universally beloved by Americans.

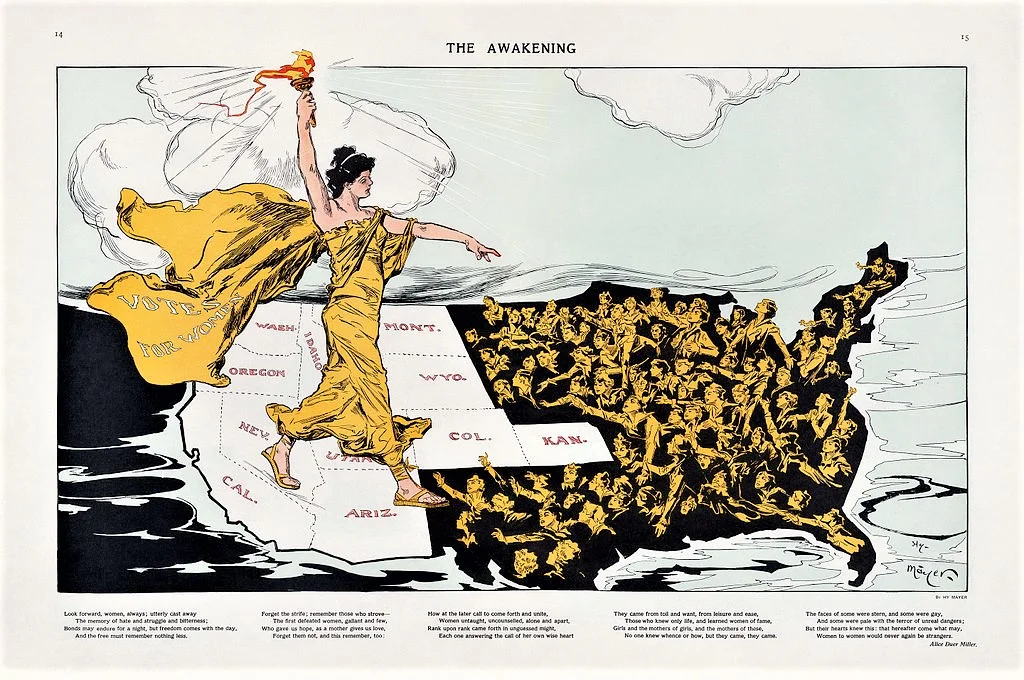

Immediately, though, cracks emerged in this façade. Blake and the nearly 200 other women who sailed to Bedloe’s Island issued a proclamation: “In erecting a Statue of Liberty embodied as a woman in a land where no woman has political liberty, men have shown a delightful inconsistency which excites the wonder and admiration of the opposite sex,” they pointed out. President Cleveland, during his speech, took no notice of the women floating directly below him, Blake brandishing a placard bearing the statement “American women have no liberty.” Suffragists around the country, however, noticed, and the statue for them became both a symbol of all they didn’t yet have and a rallying point for demanding it. In later decades, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton visited the statue, and after a 1915 measure to give women the right to vote in New York failed at the ballot box, a group of suffragists used a 1916 visit by Woodrow Wilson to drop thousands of ‘Votes For Women!’ leaflets at the statue via biplane.

The statue’s unveiling dominated headlines for weeks before and after the official date, and the ‘Cleveland Gazette’, an African-American-run newspaper with a circulation of 5,000, was no exception. On November 27, 1886, a month after the statue opened to the public, their front page ran an editorial titled “Postponing Bartholdi's statue until there is liberty for colored as well.”

“Shove the Bartholdi statue, torch and all, into the ocean,” the Gazette argued, “until the ‘liberty’ of this country is such as to make it possible for an inoffensive and industrious colored man in the South to earn a respectable living for himself and family, without being ku-kluxed, perhaps murdered, his daughter and wife outraged, and his property destroyed. The idea of the ‘liberty’ of this country ‘enlightening the world,’ or even Patagonia, is ridiculous in the extreme.”

Hubbard says including a section of the Gazette editorial in the exhibit was crucial to communicating that the Statue of Liberty posed—and still poses—an ongoing series of questions about American values. “We really had to set up the idea that the statue is sort of a promise, it represents and is a symbol of basic American and foundational American ideas,” he says. “It sets up that promise but then even from the beginning there are people who say, ‘But wait, that promise is not necessarily fulfilled.’”

A Liberty bond (or liberty loan) was a war bond that was sold in the United States to support the allied cause in World War I. Subscribing to the bonds became a symbol of patriotic duty in the United States and introduced the idea of financial securities to many citizens for the first time. The Act of Congress which authorized the Liberty Bonds is still used today as the authority under which all U.S. Treasury bonds are issued. via Wiki Reader

While the Statue of Liberty has, for most of its time in New York’s harbor, been framed as a symbol of immigration in America, at the time of its assembly, the country was just beginning to formally limit the number of people who could immigrate each year. In 1882, the federal government passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first large-scale immigration law and one that explicitly made the case for prioritizing—and restricting—immigrants based on race. Chinese-American writer Saum Song Bo responded to the Pulitzer solicitations of funds for the statue’s pedestal by sending a letter to the New York Sun:

“I consider it as an insult to us Chinese to call on us to contribute toward building in this land a pedestal for a statue of Liberty,” Bo wrote. “That statue represents Liberty holding a torch which lights the passage of those of all nations who come into this country. But are the Chinese allowed to come? As for the Chinese who are here, are they allowed to enjoy liberty as men of all other nationalities enjoy it? Are they allowed to go about everywhere free from the insults, abuse, assaults, wrongs and injuries form which men of other nationalities are free?”

It’s this idea that “liberty” is far from a fixed word with a fixed meaning that lies at the heart of the Statue of Liberty Museum’s experience. “When the designers were thinking of the statue, of course how people interpreted liberty and what it meant was already very complicated and contested,” says Hubbard. Incorporating those perspectives in the exhibit allows the space to make the point that now, more than 100 years after the Statue of Liberty’s torch first alighted, Lady Liberty still stands over New York harbor as a symbol of where the nation has come and how far it still has to go.

![Kanye West's [aka Ye] Refusal to Treat His Mental Illness Is No Excuse For His Anti-Semitism](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55f45174e4b0fb5d95b07f39/1666238183530-4WVG9SNG88HTSKQ0WWDV/Is+Kanye-West-Running-Out-of-Platforms.png)