School Spankings Are Banned Just About Everywhere Around The World Except In US

/In 19 States, It's Still Legal to Spank Children in Public Schools via NY Times. Image Mark Graham for The New York Times

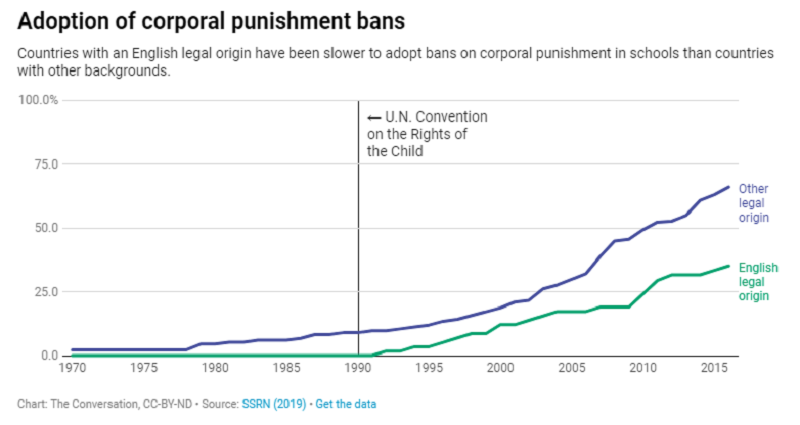

In 1970, only three countries – Italy, Japan and Mauritius – banned corporal punishment in schools. By 2016, more than 100 countries banned the practice, which allows teachers to legally hit, paddle or spank students for misbehavior.

The dramatic increase in bans on corporal punishment in schools is documented in an analysis that we conducted recently to learn more about the forces behind the trend. The analysis is available as a working paper.

In order to figure out what circumstances led to bans, we looked at a variety of political, legal, demographic, religious and economic factors. Two factors stood out from the rest.

First, countries with English legal origin – that is, the United Kingdom as well as its former colonies that implemented British common law – were less likely to ban corporal punishment in schools across this time period.

Second, countries with higher levels of female political empowerment, as measured by things such as women’s political participation or property rights – that is, women having the right to sell, buy and own property – were more likely to ban corporal punishment.

Other factors, such as form of government, level of economic development, religious adherence and population size, appear to play a much less significant role, if at all.

We are experts in education policy, international policy and law. In order to conduct our analysis, we constructed a dataset of 192 countries over 47 years using country reports from the Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children and the U.N. Committee on the Rights of the Child. Then we matched it to data from the Quality of Government Institute.

It is true that the trend of banning corporal punishment in schools aligns with the passage of the 1990 U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child – a treaty now ratified by all countries except the United States. The treaty requires nations to “take all appropriate measures to ensure that school discipline is administered in a manner consistent with the child’s human dignity.” However, as our analysis reveals, it wasn’t the treaty alone that spurred the bans.

Global shifts in corporal punishment norms

Worldwide, 732 million children attend schools where corporal punishment is allowed.

Social norms surrounding this issue have shifted over time from viewing corporal punishment as an appropriate disciplinary method to viewing corporal punishment as less acceptable. In the last several decades, for instance, experts have found that corporal punishment is harmful to children socially, cognitively and emotionally.

Consequently, many countries have adopted new laws banning corporal punishment in schools. South America and Europe have made the most progress toward outlawing corporal punishment in schools. Africa and Asia have had more mixed results. There are no bans against corporal punishment in schools in the United States, India and Australia. In the United States, corporal punishment in public schools is legal in 19 states. It is also legal at private schools in 48 states.

While we found that countries with English common law systems were less likely to ban corporal punishment in schools, the reason why requires a closer look.

Common law countries abide by the principle of stare decisis – that is, the idea that similar cases should be decided upon similarly and should rely upon precedent. This means in practice that policies on a given issue are slower to change and become somewhat “locked in” because court cases and appeals take significant time.

Conversely, countries that are based primarily in civil code are often able to change the laws mostly through legislation, which often can be nimbler and swifter. Of course, some nations, like the United States, change laws through both methods.

Our analysis found that the proportion of countries with bans increased steadily after the passage of the U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1990. We also found that not a single country with English legal origin banned corporal punishment in schools prior to the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Even among countries that ratified the convention, those with English legal origin were 38% less likely to adopt a ban.

Female political empowerment and corporal punishment bans

The degree of female political empowerment in a country is also strongly associated with how likely the country is to ban corporal punishment in schools. Why is this the case?

One possible explanation is that women in general show lower support for the use of corporal punishment. Women also more generally prefer compassionate policies over violence. And finally, female political empowerment can reflect the progressiveness of society itself, given the clear links between women’s rights and human development. Societies in which women have greater rights tend to have more progressive policies in other domains as well, such as environmental protection.

The future of corporal punishment in schools

In sum, it appears that international agreements such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child might nudge some countries to make progress on specific human rights issues – in this case, the right for children not to be physically punished in schools. Yet, the ratification of an international treaty has limited influence, it seems, in comparison to a country’s legal structure and the level of its female political participation.

The U.S. Supreme Court has never ruled the practice of corporal punishment in schools unconstitutional. In fact, it issued a decision in 1977 that noted both the historical traditionof corporal punishment in U.S. schools, and the common-law principle that corporal punishment is permissible as long as it’s “reasonable but not excessive.”

![Kanye West's [aka Ye] Refusal to Treat His Mental Illness Is No Excuse For His Anti-Semitism](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55f45174e4b0fb5d95b07f39/1666238183530-4WVG9SNG88HTSKQ0WWDV/Is+Kanye-West-Running-Out-of-Platforms.png)