Botanists and Mycologists Understand Nature's Global Communication Network

/Is Mycelium the Connective Tissue of Nature's Global Communication Network? AOC Eye

Are humans on the precipice of having scientific confirmation of "mushroom intelligence"? Such vetted research does not exist presently. But new research by Andrew Adamatzky, a computer scientist at the Unconventional Computing Laboratory of the University of the West of England, is provocative in raising a series of questions about intelligent life in the world of fungi.

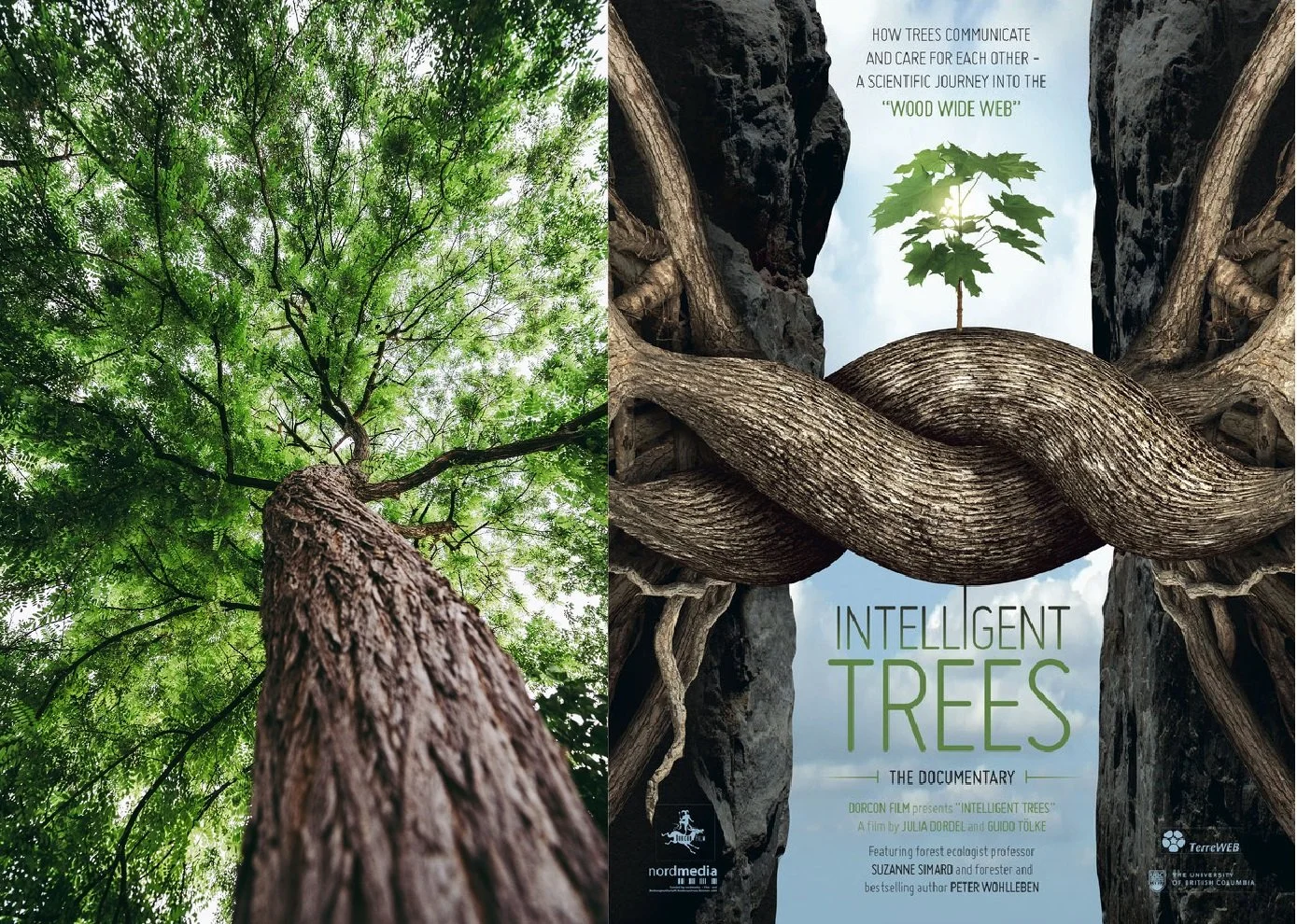

The Wood Wide Web

Indications of 'Earth's natural internet' date back to the 1885 when the German botanist and mycologist Albert Bernhard Frank coined the term "mycorrhiza". The mycorrhizae [plural of a single cell mycorrhiza] exist as miniscule, amost microscopic threads called hyphae. These hyphae branch into a complicated web or patchwork called mycelium.

In the words of The National Forest Foundation: "Taken together, myecelium composes what’s called a “mycorrhizal network,” which connects individual plants together to transfer water, nitrogen, carbon and other minerals. German forester Peter Wohlleben dubbed this symbiotic network affecting about 90 percent of plant life on the planet -- including trees -- the “woodwide web.” It is through the mycelium that trees 'communicate.'

Botanists and mycologists have understood this grand symbiotic relationship between fungi and plants for over a century. But positing the existence of a linguistic communication system founded on 'intelligence' is another subject entirely.

"A forest is much more than what you see," says ecologist Suzanne Simard. Her 30 years of research in Canadian forests have led to an astounding discovery -- trees talk, often and over vast distances. Learn more about the harmonious yet complicated social lives of trees and prepare to see the natural world with new eyes in her 2016 TED Talk that teaches us how trees talk to each other.

Her hands-on, simple research is staggering to digest, not only around her confirmation of how trees communicate with each other — but where mycelium comes into play underground.

Simard’s TED talk clarifies beautifully the commentary in the above paragraphs.

"The Secret Life of Plants"

Almost 50 years ago, Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird published in 1973 their mindbending book "The Secret Life of Plants", described as "a fascinating account of the physical, emotional, and spiritual relations between plants and man."

Reissued and updated in March, 1989, the title -- called "beloved" 16 years after its initial publication date -- cast fresh eyes on the "rich psychic universe of plants", as it explored plants' responses to human care and nurturing, plants' surprising reaction to music, their lie-detection abilities, their creative powers and much more.

"The Secret Life of Plants" affirmed the deep ties that humanity has with nature -- even when we disregard its importance in our lives through our actions. Most humans take the natural world for granted, as if it will always exist at our disposal to inspire our senses, grow food for our stomachs, and regulate temperatures on earth.

We do not consider this relationship tenuous, inspiring us to act with care with plants and their own lives, so that we do not perish as a species.

Decades of research since Tompkins and Bird shared their account of the special relationship between humans and plants, has confirmed their central thesis about interactions between humans and plants.

The possibility that fungi have their own electrical language to communicate information about both opportunity and resources nearby, and also danger, could signal a vast underground intelligence network that covers much of the globe.

More reading:

If Fungi Could Talk: Study Suggests Fungi Could Communicate in Structure Comparable to Humans Discover Magazine