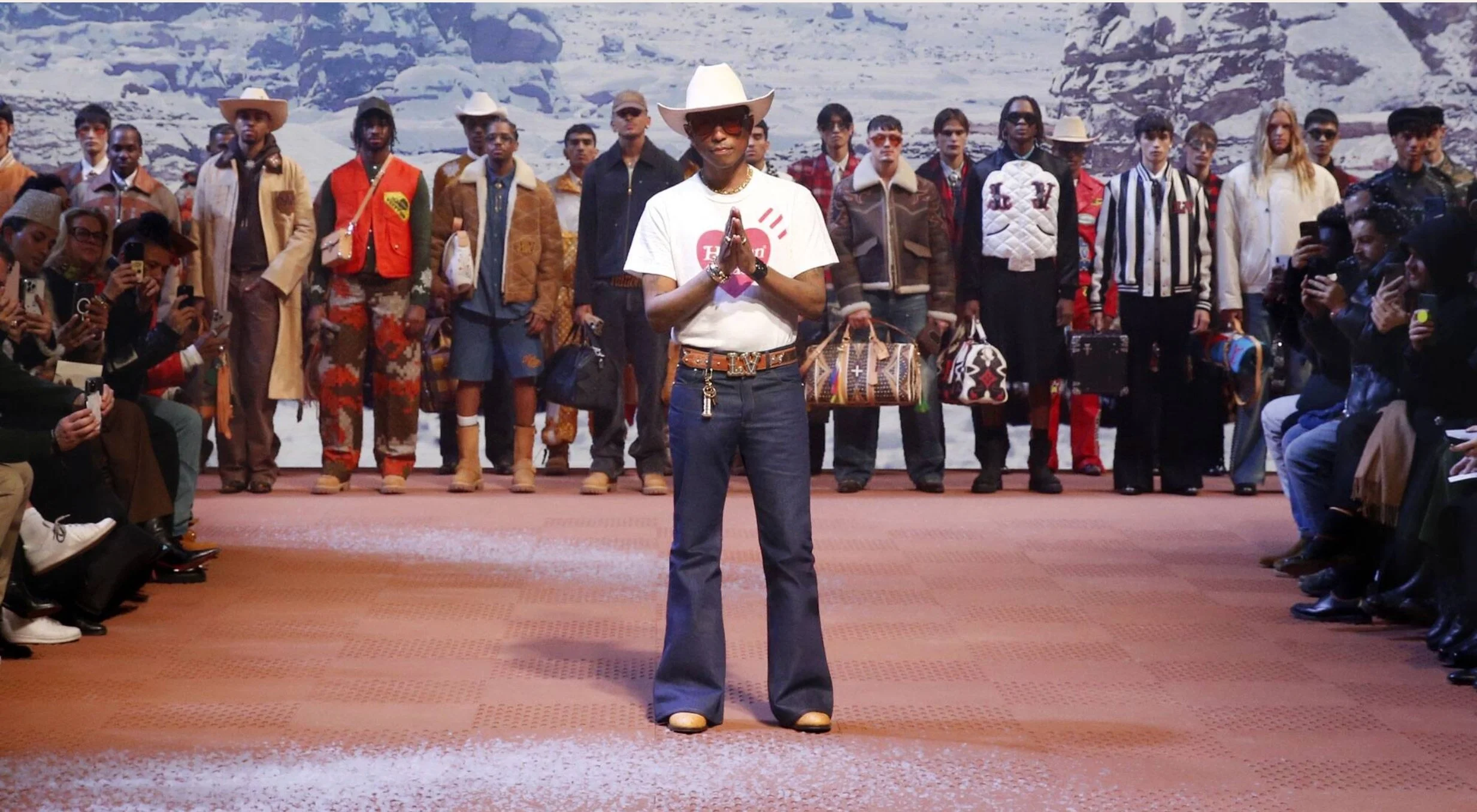

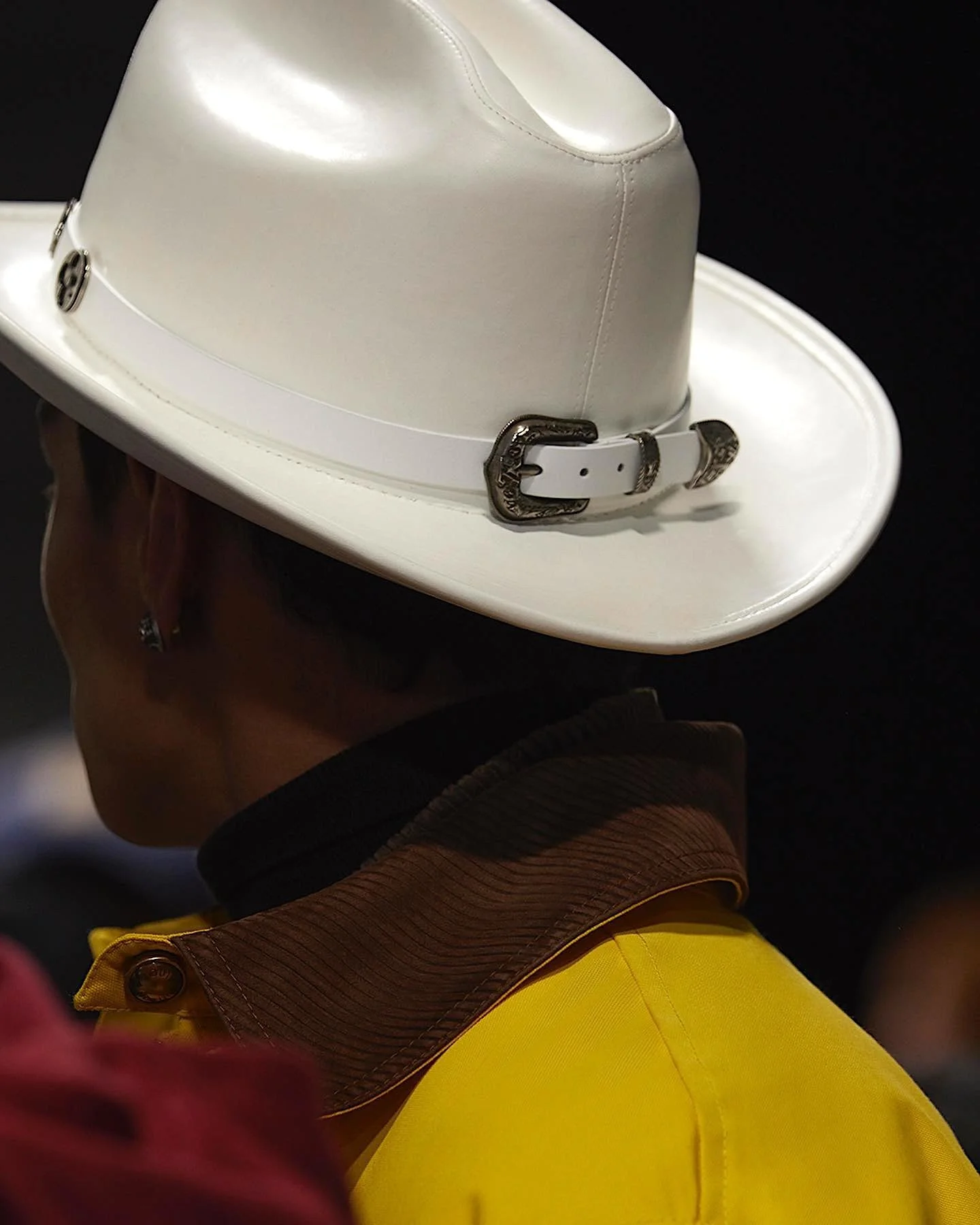

America’s Black Cowboys, As Tributed by Pharrell Williams for Louis Vuitton Fall-Winter 2024 Men’s Collection: Pt 1 of an American-French Cowboys Story

/Historians estimate that in the latter half of the nineteenth century, one in four American cowboys was black. Anne of Carversville seriously doubts that this reality is taught in the history classes of American schools. Additionally, an estimated 12% of cowboys were Mexican.

Thanks to the January 18th Louis Vuitton Fall-Winter 2024 Men’s Collection show at the Jardin d’Acclimatation in Paris, this historical lens of exploration is opened wide. AOC is both incredulous and excited to tell this story. But first — a look at the highly-praised, Louis Vuitton Men Creative Director Pharrell Williams Fall-Winter 2024 show.

Black Cowboys and Slavery

The history of black cowboys in America is deeply intertwined with the legacy of slavery and the Civil War. Prior to Emancipation, many enslaved African Americans were forced into labor on plantations, including working with cattle. Other African Americans went west to California as slaves of gold miners and to Utah as slaves of Mormons.

Texas became the largest home to black cowboys. The land was colonized by Spain in the 1500s and became a territory belonging to Mexico during the first half of the 19th century. Although Mexico was opposed to slavery, white Americans brought slaves with them as they settled the Texas frontier and created cotton farms and cattle ranches.

The Smithsonian estimates that if slaves accounted for a quarter of the Texas settler population in 1925, that number grew to over 30 percent in 1960, quantified as 182,566 slaves living in Texas, based on the census.

Black cowboys showcased exceptional horsemanship skills and contributed significantly to cattle drives, rodeos, and ranching operations. Their contributions extended beyond labor, as black cowboys played key roles as trail guides, scouts, wranglers, and even as lawmen.

Their stories often went untold — AOC knows none of this history — or were overshadowed by mainstream narratives that told American history through the lens of white superiority in all activities related to the cowboy life.

Texas Is for Cowboys Loyal to the Confederacy . . . Until They Weren’t

Texas was admitted to the union on December 29, 1845, having existed as an independent country for a decade. The 28th state sought immediate annexation by the US in 1836, but found itself embroiled in political turmoil and the fight over admitting new slave-owning states to America.

During this time, much evidence — including oral histories, as documented in Kenneth W. Porter’s book “Black Cowboys in the American West, 1866-1900” — argues that black and white cowboys worked together more commonly than not. Porter stipulates that pay was the same for both groups of men.

Unlike the military, there weren’t groups of black cowboys and white cowboys. Away from women, the men worked well together. This point was made in multiple research sources, AOC has reviewed.

Texas joined the Confederacy in 1861, as a proud slave-owning state. Unlike states like Georgia or Virginia, the Civil War hardly reached Texas soil. However, white Texans took up arms to fight alongside their Confederate brethren soldiers in the East.

With Texas ranchers away fighting the Civil War, they and their families became very reliant on their slaves to maintain the land and herd cattle. This precarious balance of slave-owner lifestyle balance would change as black cowboys joined the Union army.

Black Cowboys and the Union Army

During the Civil War, thousands of black men escaped or were freed from slavery to join Union forces. Initially, President Lincoln was very reluctant to allow runaway slaves to serve in the Union army.

As Union losses mounted in 1861, President Lincoln persisted in his opposition to allowing slaves to enlist. What followed was an ongoing ‘stalemate’ where multiple slaves turned themselves over to Union generals — down the road about 15 minutes from Pharrell and me came the first major inductions of slaves into the Union army. Washington DC said ‘no’ and the Union generals did it anyway.

To be clear, President Lincoln was seriously worried about losing the support of the anti-slavery states.

The narrative around black cowboys and all runaway slaves joining the Union army was about to change. AOC turns to the National Museum of the United States Army:

In 1862, as the war became increasingly bloody, official policy shifted toward enabling African Americans the right to fight for themselves. Substantial numbers of African Americans, led by African American intellectuals and abolitionists, repeatedly lobbied the government until their pleas could no longer be ignored. With Union forces depleted almost 40% due to deaths, wounds, illness, and desertion, and with many initial enlistments ending, the Lincoln administration relented in the summer of 1862. Congress, with President Abraham Lincoln’s support, passed the Second Confiscation Act and Militia Act on July 17, 1862. These acts freed any enslaved person who left a “disloyal” owner in the rebellious states and allowed the president to “employ as many persons of African descent as he may deem necessary.”

Because we’re moving away from the black cowboy narrative into a more black experience one, it’s time to pause Part 1 with a perfect segue into Part 2.

The first regiment of Confederate country blacks was raised in Louisiana as Louisiana Native Guards, then renamed the Corps D’Afrique.

That name resonates — ‘Corps D’Afrique’ — because whether we have one more installment in our Louis Vuitton Men’s American History lesson — or two [probably] — this black cowboys story is headed for Paris and our [Pharrell’s and mine] beloved France.

AOC research is a perfect example of “Ask and you shall receive,” particularly when your mind assumes that there’s no such thing as a stupid question.

Among the reasons AOC and Anne are so emotionally attached to LVMH and Louis Vuitton is that I’ve learned more about American history writing about their brands than I ever learned in school. I truly am a product of France — having spent so much time working there — as I am an American.

Vive la France! And Vive Pharrell for Louis Vuitton. ~ Anne

All images via Louis Vuitton IG