Scientists Find Three Kinds of Early Humans Living Together in South Africa

/The drimolen fossil site. (Andy Herries)

By Brian Handwek. First published on SmithsonianMag.com

Scientists studying the roots of humanity’s family tree have found several branches entangled in and around a South African cave.

Two million years ago, three different early humans—Australopithecus, Paranthropus, and the earliest-known Homo erectus—appear to have lived at the same time in the same place, near the Drimolen Paleocave System. How much these different species interacted remains unknown. But their contemporaneous existence suggests our ancient relations were quite diverse during a key transitional period of African prehistory that saw the last days of Australopithecus and the dawn of H. erectus’s nearly two-million-year run.

“We know that the old idea, that when one species occurs another goes extinct and you don’t have much overlap, that’s just not the case,” says study coauthor Andy Herries, a paleoanthropologist at La Trobe University in Australia.

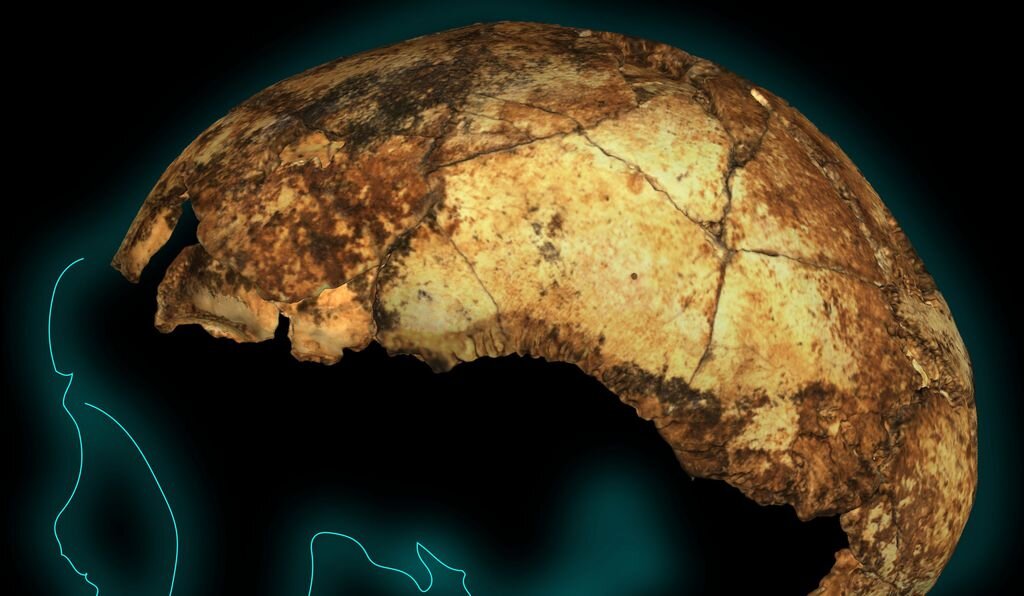

Homo erectus cranium with stylized projection of the outline of the rest of the skull. (Andy Herries, Jesse Martin and Renaud Joannes-Boyau)

Three Species, One Place

Australopithecus africanus is the most primitive of this trio. The lineage dates to 3.3 million years ago and combines human features with ape-like attributes including long, tree climbing-arms. Despite these intermediate features, Australopithecus’s exact relation to modern humans remains unknown. The species is thought to have died out around 2 million years ago.

Paranthropus robustus, an offshoot of the human family tree not considered a direct human ancestor, is known for large, powerful jaws and teeth that could pulverize a diet of nuts, seeds, roots and tubers. Paranthropus lived from perhaps 2 million years ago (the remains described in this study are the earliest known) until about 1.2 million years ago.

Homo erectus was the first ancestor of modern humans to have human-like body proportions and the first to appear outside of Africa. The species appeared in what is now the nation of Georgia 1.85 million years ago and survived in some Indonesian enclaves until as recently as 117,000 years ago. It’s generally believed that they first evolved in Africa, and the cranium find described at Drimolen would push back their earliest-known occurrence anywhere in the world by more than 100,000 years.

“It’s an excellent paper, and it looks quite convincing,” says Fred Spoor of the Natural History Museum, London. “It would have been ideal if there was more of the cranium, but I think they make a very good case that it’s Homo and that the closest affinities are probably with erectus. And that would make it quite likely the oldest Homo erectus-like thing.”

The Drimolen excavations and excavated fossils. (Andy Herries)

“I have no doubt that they have something that is of the genus Homo,” adds Rick Potts, a paleoanthropologist and head of the Smithsonian’s Human Origins Program. But Potts notes that the incomplete skull doesn’t show all the telltale features that would characterize it as Homo erectus or some other relative. Furthermore, the cranium belongs to a 2- or 3-year-old child, for which comparisons are scarce. “I’m not 100 percent sure that they have Homo erectus. And that would be one of the really interesting parts of the study, because if they do have Homo erectus then it is the earliest known in the world.”

Out of Africa, or Within Africa?

If Herries and colleagues are correct that they have found Homo erectus, the early dates of the find pose an intriguing question: How did the species arrive in South Africa?

One possibility is that H. erectus originated here and later spread to East Africa and then out of the continent. However, Herries says that the discovery of the oldest-known bones doesn’t necessarily mean H. erectus started in this locale. Perhaps they migrated to the area.

“It seems that Homo erectus and Paranthropus and stone tools all suddenly occur in South Africa at this point,” Herries says. “This suggests that we’ve got movement into the region, and I think it’s really part of this same sort of story. We talk about 'Out of Africa' a lot, but the hominids didn’t know they were going out of Africa. They were just moving.”

Herries and colleagues cite some evidence for non-hominid migrations that may lend weight to this theory. An extinct prehistoric zebra and springbok appear at South African sites during this same time, suggesting some environmental factors spurred their relatively sudden migration into the region from regions further north where they are known to have lived earlier.

It’s a question of putting our ancestors in their place ecologically, Potts says, which drives much of his work on hominin evolution. “We think a lot about what’s going on with other mammals when looking at explanations of human evolution,” he says. “This period around 2 million years ago is one of prolonged, very high climate variability in Eastern Africa. I think that’s just the right conditions for animals to be moving around to track different environments.”

If it was a migrant, H. erectus would have moved into an area that was already occupied by other ancient hominids and shared the same landscape with them for a significant time. “The fact that in a small area in South Africa you have not just three species but three different genera, … at the same time is neat,” says Spoor, who this week published a study modeling the brains of the famed hominid Lucy and her kin. “This will certainly put Drimolen back on the map.”

“We talk a lot about [diverse species coexisting] with Neanderthals, modern humans, and Denisovans, and we can see that with DNA, but we don’t have that ability with this earlier stuff,” adds Herries. “I’m sure it happened and this may be one of the first instances where we can really see it.”

La Trobe University PhD student Angeline Leece in front of fossil bearing brecccia at Drimolen. (Jesse Martin)

A Dating Dilemma

The Drimolen Paleocave System is part of South Africa’s Unesco World Heritage Site called the Cradle of Humankind, a collection of limestone caves near Johannesburg that are one of Africa’s two great sources of hominid fossils. More than 900 have been found, representing at least 5 different species, during excavations that began nearly a century ago.

The big problem in South Africa has been dating all these finds. East Africa’s rift valleys, the continent’s other great hominin fossil source, feature layers of volcanic ash that can be dated by measuring the decay of radioactive elements, thereby dating the fossils within. In many South African caves, by contrast, older, fossil-filled sections have collapsed into lower areas. Modern humans operated mines in the area, too. The result is a confusing and complicated landscape that defies easy reconstruction.

Herries, who specializes in geochronology, says the Drimolen site is a bit different. It’s a small cavern that was deposited during a short period when water sunk into the cave, leaving a large sediment cone in the middle in which the fossils were found. Studies of the cave sediments show that this happened during a short window of time when Earth’s magnetic field flipped, a major help in dating the finds.

“That’s a huge advantage because we know when these magnetic changes occurred in the past,” Herries says. Scientists know when the field flips because the event leaves magnetic patterns in volcanic rock, especially in lava on the ocean floor, leaving a record of these reversals.

By using the known rate at which uranium decays into lead the team dated a tiny flowstone in the middle of the cave, formed by minerals in water that moved across the cave walls and floor, to about 1.95 million years ago—just in time for the magnetic field reversal. “That’s the critical combination that allowed us to date those layers, and date the bits where the crania come from which are slightly older than that.” The team also dated molars associated with the fossils using Electron Spin Resonance techniques with wider margins of error that nonetheless correlate to the same period. “My hope is that people will be convinced that we can date these cave sites in South Africa effectively now. It takes a lot of hard work, and a bit of luck.”

Potts was among those convinced by the dating but found himself even more impressed by the significance of the multi-species fossil find—something that until now was only seen in northern Kenya’s Turkana Basin, where four hominin lineages once coexisted.

“They’ve done a great job demonstrating that while there is this amazing diversity in East Africa (Turkana), there is an amazing but different combination of species diversity in South Africa, with different lineages of hominins hanging around at the same time. Now the number of such sites is doubled. That’s quite important in my view.”