Art by Congo, the Famous Painting Ape, to Go on Sale at London's Mayor Gallery

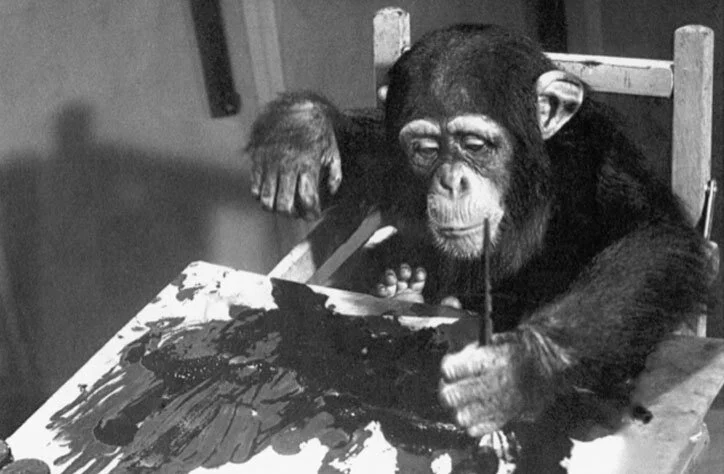

/Congo the chimpanzee using the primitive grip (1957), copyright Desmond Morris.

By Jason Daley. First published on Smithsonian.com

In December, a beloved 20th-century artist will finally get his due when a lot of 55 paintings by Congo the chimpanzee goes on exhibit at the Mayor Gallery in London.

The paintings are owned by Desmond Morris, who hosted “Zoo Time,” a U.K. show broadcast from the London Zoo in the 1950s.

Morris was no ordinary television host. He was a noted abstract painter, an ethologist (someone who studies animal behavior) and zoologist. He’s also the author of many popular science books, including 1967’s The Naked Ape, which examines humans through a zoologists lens.

As Nigel Reynolds at the Telegraph reports, one day Morris offered the young chimp Congo a pencil and the rest was history. “He took it [the pencil] and I placed a piece of card in front of him,” Morris recalls. “This is how I recorded it at the time, ‘Something strange was coming out of the end of the pencil. It was Congo’s first line. It wandered a short way and then stopped. Would it happen again? Yes, it did, and again and again.’”

Morris realized Congo could make circles and even had a sense of composition; he filled in parts of the paper to balance his drawings. Eventually, Morris let Congo paint. While he never made any representational art, he did appear to have some chops when it came to abstract work, favoring a radiating fan pattern.

“It was truly art for art’s sake. Congo became increasingly obsessed with his regular painting sessions. If I tried to stop him before he had finished a painting, he would have a screaming fit,” Morris says. “And if I tried to persuade him to go on painting after he considered that he had finished a picture, he would stubbornly refuse.”

Morris went on to feature the painting chimp on “Zoo Time,” and he became something of a sensation. In 1957, Congo’s work went on display at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. Art world luminaries including Picasso bought his work. Joan Miró swapped two of his pieces for one of Congo’s 400. Upon viewing Congo’s work, Salvador Dalí quipped the “hand of the chimpanzee is quasihuman; the hand of Jackson Pollock is totally animal!”

As Morris explains, “The more serious the artist, the more they understood what Congo was doing because they could see that he was positioning his lines.” That being said, he cautions people from overhyping Congo’s artwork. Rather, as he tells Taylor Dafoe at artnet News, it’s what Congo’s art represents that's most important. “Congo’s ability to make a controlled abstract pattern and then to vary it in different ways meant that inside the ape brain there was already an aesthetic sense—very primitive but nevertheless present in a non-human species,” he says. “Watching him paint was like witnessing the birth of art.”

James Mayor, director of the gallery that will show Congo’s work, also praises Congo, who died of tuberculosis in 1964 at the age of 10. Speaking with Rory Sullivan of CNN, Mayor declares that the chimp’s paintings are “actually very good…He was a fascinating painter. People would imagine he’d just grab a pencil or a paper, but...he’d have several colors and he'd think before he painted...He was extraordinary.”

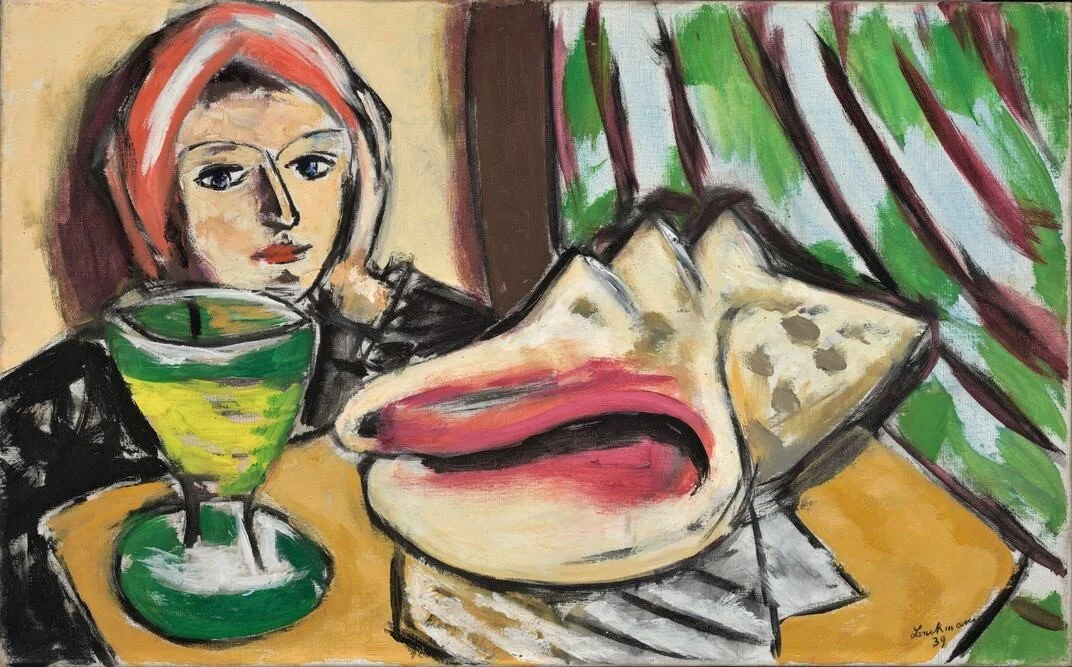

Congo the chimpanzee 36th Painting Session (1958), paint on paper, copyright Desmond Morris.

Most of Congo’s 400 works of art were sold after the 1957 exhibition. Another group was sold at the Mayor Gallery after being exhibited with two other primate artists in 2005 in a show called “Ape Artists of the 1950’s.” That same year, three of Congo’s paintings sold for a combined $25,000 at auction, 20 times the expected price. It’s believed the latest batch of paintings will sell for a total of around $250,000.

Morris, who is now 91, tells the AFP that while he plans to hold onto the scientific research notes he made during his work with Congo, he decided that it was time to make the paintings available to other collectors.

There is one piece, however, that he’s not ready to part with: He tells Dafoe that Split Fan Pattern with Central Black Spot holds a special place in the Congo oeuvre. Apes typically fan out leaves to make their nests, which may explain why Congo was so enamored with that pattern in his early work. But in Split Fan, Morris explains, Congo altered that fan pattern for the sake of composition, the first time he made a purely aesthetic decision.

Desmond Morris with Congo’s painting Split-Fan Pattern with Central Black Spot (1957).