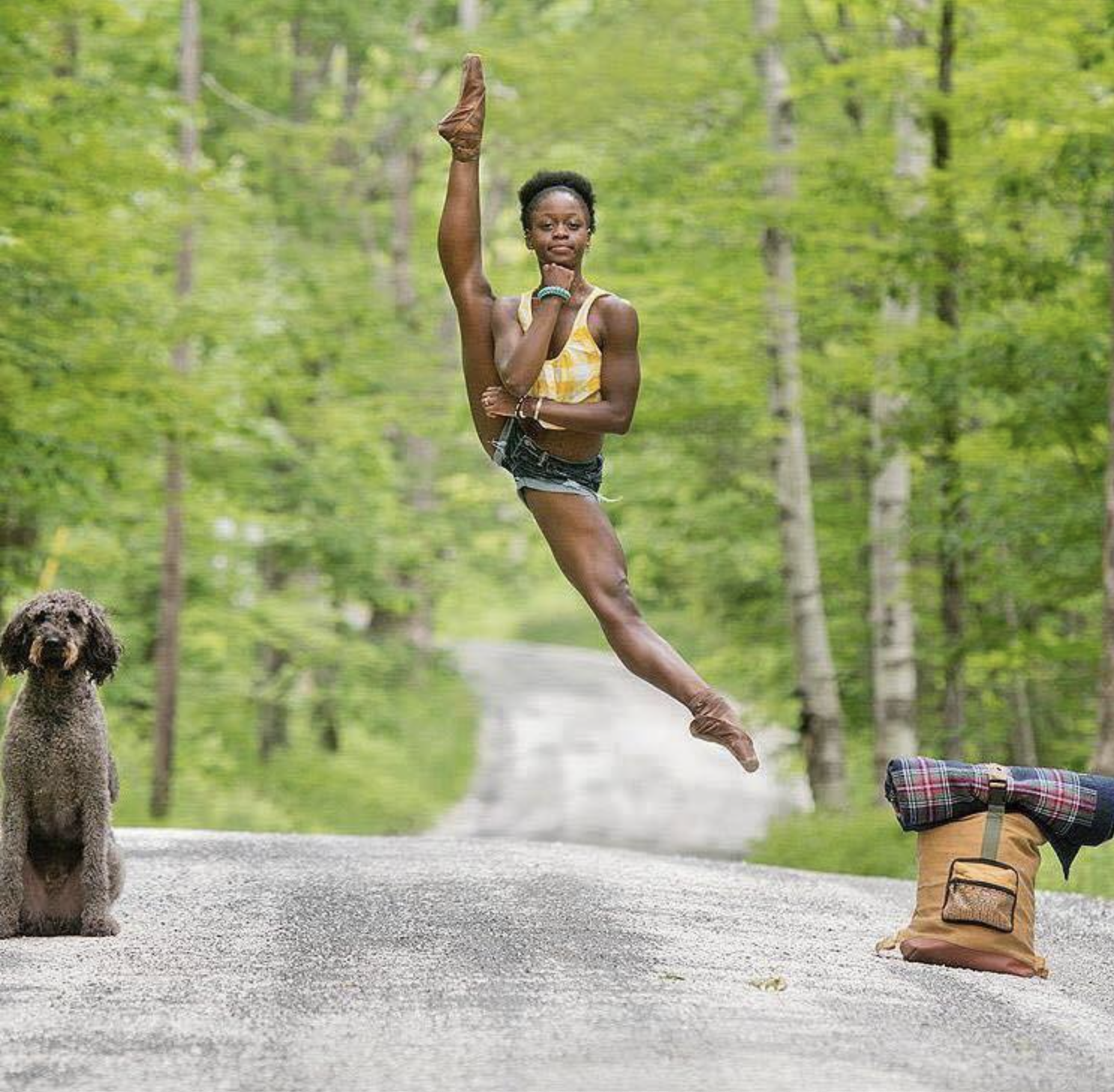

Dancer Michaela DePrince Soars Beyond Human Expectations & Leaves Us Breathless

/This astonishing photo of ballet dancer Michaela DePrince has 4,568 shares on Facebook, leaving readers raving while spellbound. Many said: “This is surely one of the most beautiful photos I’ve ever seen.”

Michaela’s story is even higher impact, and none of the common words like ‘resilient’ or ‘courageous’ apply. Michaela’s story is one of triumph and also an American couple promoting our best values, the less well-known stories that rarely make headlines.

Michaela DePrince as Mabinty Bangura

Exposure.org.uk shares Michaela’s history as a girl named Mabinty born in 1995 in Sierra Leone, West Africa. Then considered one of the most dangerous places in the world, Mabinty’s father became one of 300,000 people killed in a civil war that lasted from 1991 to 2002. Her mother died of starvation, leaving Mabinty via her uncle to be put in an orphanage at age three.

Because Mabinty suffered from a skin condition called Vitiligo, she was labeled a ‘devil child’ and always treated differently. Food, clothes and other life essentials were handed out according to a best to worst child ranking system at the orphanage. Of the 27 children, Mabinty was known as ‘number 27’.

A teacher who befriended her was murdered by rebels before her eyes. The BBC explains that pregnant women experienced a special kind of mutilation.

“If they found a boy they would let the woman go, or kill the mother and save the child,” DePrince says. “But they found a baby girl when they cut my teacher’s stomach open, so they cut her arms and legs off.”

DePrince says that the younger boy, perhaps in an effort to impress the older soldiers, took a machete to her stomach too. She blacked out - but was rescued when her mat-mate raised the alarm.

Then the universe sent Mabinty a picture one day.

“There was a lady on it, she was on her tippy-toes, in this pink, beautiful tutu. I had never seen anything like this - a costume that stuck out with glitter on it, with just so much beauty. I could just see the beauty in that person and the hope and the love and just everything that I didn’t have.

“And I just thought: ‘Wow! This is what I want to be.’”

DePrince ripped the photograph out of the magazine and, for the lack of anywhere else to keep it, stuffed the treasured scrap in her underwear.

“It represented freedom, it represented hope, it represented trying to live a little longer,” she recalls. “I was so upset in the orphanage, I had no idea how I got through it but seeing that, it completely saved me.”

When an international organization seeking to place orphans in adopted homes in safe countries, Mabinity didn’t receive any of the ‘family books’ from the United States, being ‘number 27’ and a ‘devil child’. She wasn’t going anywhere.

In yet another moment of horror, Mabinty’s life changed in an entirely different direction. The orphanage was warned it would be bombed and totally destroyed. Mabinty ‘number 27’ hit the road with her friend, also named Mabinty, or ‘number 26’. The girls walked for miles through Sierra Leone until, miraculously unharmed by rebels, they reached a refugee camp.

‘Number 27’ was reborn in that camp, along with ‘number 26’. Her American parents Elaine and Charles DePrince were hoping to adopt Mabinty Suma, ‘number 26’.

Upon learning of her story and how the little girl with Vitiligo was unlikely to be adopted at all, the couple couldn’t envision separating the two Mabinty girls.

And so at age four, Mabinty Bangura was renamed Michaela De Prince, and she joined her parents and new renamed sister Mia, along with a third girl Mariel in starting a new life in Cherry Hill, New Jersey. Note that the DePrinces are adoptive parents to eight other children, in addition to two biological children.

Michaela (l), dad Charles and Mia (r) DePrince on their first Thanksgiving in America.

The Ballerina Blooms

Michaela’s first confusion came when her new mother wore no ballet shoes. “I was looking at people’s feet because I thought: ‘Everyone has to have [ballet] pointe shoes, they have to have pointe shoes because these are people from the US!’” The young girl’s confusion grew when she found no ballet shoes in Elaine’s luggage either.

Settled in Cherry Hill, Michaela’s new mother noticed at once her daughter’s obsession with ballet. Gifted with a Nutcracker video, Michaela watched it over 150 times. By the time she saw a live performance of the Nutcracker, Michaela explained to her mom all the places where the dancers missed their steps.

Elaine enrolled five-year-old Michaela in the Rock School of Dance in Philadelphia, making the drive back and forth every day. It wasn’t too many years before Michaela encountered the well-understood racism of the ballet world. At age eight, she was told she couldn’t perform as Marie in The Nutcracker because “America’s not ready for a black girl ballerina” and a year later her mother was told that black dancers weren’t worth investing in.

DePrince was awarded a scholarship to study at the American Ballet Theatre’s Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School of Ballet for her performance at the Youth America Grand Prix. She was one of the stars of the 2011 documentary film First Position, which follows six young dancers vying for a place in an elite dance company. After graduating from school, Michaela joined the Dance Theatre of Harlem, where she was the youngest member of the company.

A Poppy Among the Daffodils

In July 2013, Michaela moved to The Netherlands, joining the junior company of the Dutch National Ballet, based in Amsterdam. In August 2014, she joined the Dutch National Ballet as their only dancer of African origin.

Interviewed by Marina Harss inDanceTabs, October 2013, Michaela talked about racism in ballet, referring to herself as a poppy in a field of daffodils.

I think that it is a rare artistic director that is willing to hire a black ballerina and promote her through the ranks. The problem begins with the corps de ballet. I think that artistic directors like the corps to look homogenous. The corps is the backdrop to the story, a forest, a snowstorm, a flock of birds or a field of flowers. One red poppy in a field of yellow daffodils draws the audience’s eyes to the one poppy. However, I don’t think the answer is to cull the poppy. I think it’s to scatter more poppies about the field of daffodils. With more black ballerinas in the corps, there will inevitably be more black ballerinas rising. I think that if these artistic directors or perhaps the boards of professional ballet companies want to draw larger more heterogeneous audiences, they need to be willing to change the look of the corps de ballet.

I suspect that the resistance to raising black ballerinas through the ranks might be due to an old-fashioned way of looking at beauty. Our ideal of a perfect ballerina is based on Russian ballet with its willowy blondes. If a director does not appreciate the aesthetics of African beauty, he will not want to promote a black ballerina to the status of prima, because the prima is supposed to be the most beautiful dancer. She represents the aesthetics of classical ballet, which right now are Eurocentric.

Marina Harss pursue the topic of race further with Michaela, asking about the comment of Virginia Johnson, Artistic Director of Dance Theater of Harlem, when asked if her dancers were committed to being in a company of color.

Yes. Though I have to say, Michaela DePrince has left us. She got a contract with the Dutch National Ballet. She really did want to be in a white company. That was important to her. But our dancers know what we’re about. We’re about the art form and moving it forward. We’re not a social justice organization. It’s not just about being black, it’s about the art form of ballet. It’s not just a job; it’s not just a company, it’s a mission.

Michaela responded:

I felt that statement misrepresented me. I left because I didn’t feel artistically fulfilled. I wanted to dance with a large top tier world-class classical or neoclassical company that had a large repertoire. The fact that such companies are white is unfortunate. However, I feel strongly that it is time for classical ballet to be integrated. As I said earlier, rather than cull the one poppy from the field, scatter more of them about. I feel that by accepting a contract with a company like the Dutch National Ballet, Paris Opera Ballet or any of the other American or European world-class ballet companies I am doing my part, maybe even leading the movement to achieve that integration. Dancing with a company that is considered to be a “black” company will not further that cause.